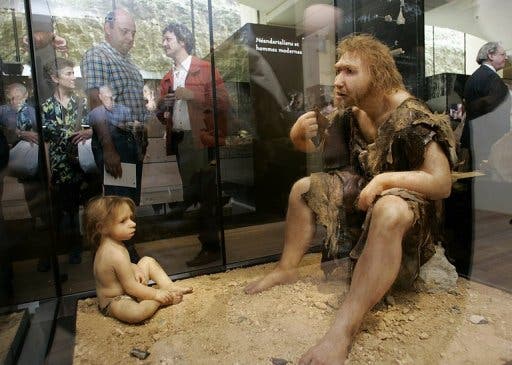

The mating between Neanderthals and modern homo sapiens has been a highly controversial matter between scientists in the anthropology scene for decades now. That was until last year, however, when anthropologists convened that the two related species did indeed mate, but the genes passed down from Neanderthals were inactive.

Recently, there’s been another reason for contradiction, once with the publishing of a new study this Thursday by Stanford scientists in which they outline how DNA inherited from Neanderthals and newly discovered hominids, dubbed the Denisovans, has contributed to the immune system of modern day man among populations in Europe, Asia and Oceania. Just so you can get an idea of how volatile studies and discoveries in the scientific world can be.

Sex with Neanderthals made modern day humans stronger

“The HLA genes that the Neanderthals and Denisovans had, had been adapted to life in Europe and Asia for several hundred thousand years, whereas the recent migrants from Africa wouldn’t have had these genes,” said Dr. Peter Parham.

“So getting these genes by mating would have given an advantage to populations that acquired them.”

A similar scenario was found with HLA gene types in the Neanderthal genome.

“We are finding frequencies in Asia and Europe that are far greater than the whole genome estimates of archaic DNA in modern humans, which is 1-6%,” said Professor Parham.

From the analysis, the scientists estimated that more than half of the genetic variants in one HLA gene in Europeans could be traced back to Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA. Asians owe up to 80%, and Papua New Guineans up to 95%.

Skepticism among other scientists

While this is a remarkable, ground-breaking study by all means, some scientists are still reluctant to accept its impact on the immune system and, consequently, passing on off active genes.

“I’m cautious about the conclusions because the HLA system is so variable in living people,” commented John Hawks, assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US.

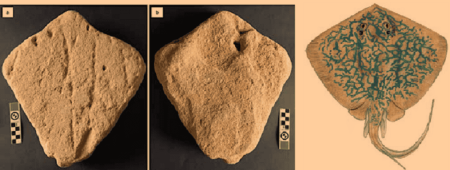

Denisovan tooth DNA from a tooth (pictured) and a finger bone show the Denisovans were a distinct group“It is difficult to align ancient genes in this part of the genome.

“Also, we don’t know what the value of these genes really was, although we can hypothesise that they are related to the disease environment in some way.”

The study was published in the latest edition of the journal Science.