A dangerous insect-killing chemical that was banned 40 years ago is still polluting deep-sea fish and sediments near the southern coast of California, according to a new research.

Even though the U.S. banned the chemical dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in 1972, the researchers believe it is still getting into marine food chains.

The pollution is still present in an area about 15 miles from Catalina Island, which was used as a dumping site for DDT in the 1940s and 1950s, as stated in a study published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters on Monday. The Environmental Protection Agency declared this offshore region near Palos Verdes an underwater hazardous waste site in 1996, and the company responsible was ordered to pay $140 million in damages four years later..

Lihini Aluwihare, a professor at the University of California San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and co-author of the study, said, “The deep-sea creatures are contaminated with these DDT-related chemicals, despite not spending much time near the surface.”

From 1948 to 1961, ships from the Montrose Chemical Corporation released industrial waste with up to 2 percent pure DDT directly into the Pacific Ocean in this location, according to the researchers.

The study estimates that around 100 tons of DDT ended up in the sediments of this offshore area, causing harm to the local wildlife such as sea lions, dolphins, bottom-feeding fish, and California condors.

Research has also shown that the DDT contamination has caused health issues in local marine animals, including sea lions, dolphins, bottom-feeding fish, and coastal California condors.

However, it is still unknown whether these impacts are spreading through the undersea ecosystem in a way that could be dangerous for wider marine life or for humans.

Lihini Aluwihare stated, “Determining the current spread of DDT contamination in deep-sea food chains helps in considering whether these contaminants are also moving up through deep-ocean food chains to species that people might eat.”

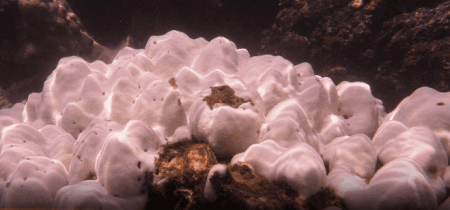

Scientists from Scripps and San Diego State University gathered sediment samples and deep-sea animals from one of two dump sites in the area to test them for DDT-related compounds.

Upon studying the sediments, they found 15 different such chemicals, 14 of which had been previously found in birds and marine mammals in Southern California.

The researchers also caught 215 fish in three areas near the dump site, finding 10 DDT-related compounds in the animals, all of which were present in the sediment samples. Fish at shallower depths had lower levels of the pollutants and two fewer DDT-related compounds compared to the deep-sea fish.

However, the researchers pointed out that none of these fish are bottom-feeders, which means there must be another way they are being exposed to the pollutants. One possibility they are considering is that sediments in the area are getting stirred up around the dumping site and entering the food chains.

The main author Margaret Stack, who is an environmental chemist at San Diego State University, said that it is clear from the evidence that DDT compounds are getting into the deep ocean food web, no matter where they come from.

Stack also mentioned that this is worrying because it wouldn't be difficult for the DDT to end up in marine animals or even people.