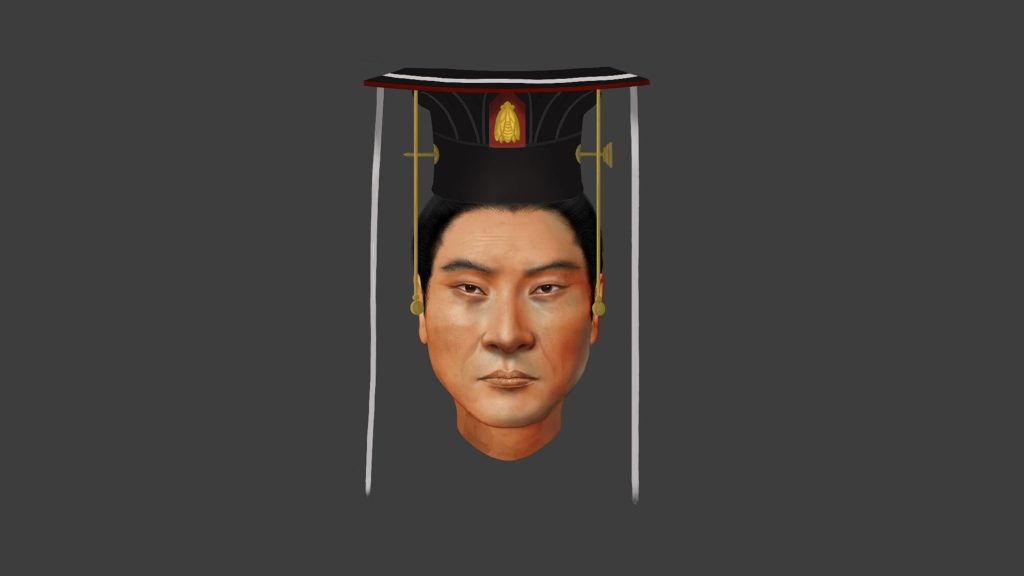

A group in China utilized ancient techniques to rebuild the face DNA to form the face once again of a king who controlled for 1,500 years ago. Emperor Wu was the leader of the Northern Zhou dynasty from 560 to 578 CE. The facial recreation is explained in a study released March 28 in the journal Current Biology. The research gives insight into how Emperor Wu potentially died and the movement of a nomadic empire that previously ruled parts of northeastern Asia.

As a ruler, Emperor Wu is celebrated for creating a strong military and uniting a northern area of China after defeating the Northern Qi dynasty. Emperor Wu’s grave was found in northwestern China in 1996. Archaeologists found several bones, including an almost complete skull.

Since that time, ancient DNA research methods have advanced and the team from this current study was able to retrieve over 1 million single-nucleotide changes (SNPs) on his DNA. Each SNP–or snip–indicates a difference in a single building block of DNA. SNPs happen commonly throughout DNA and each person's genetic code has about four to five million of them. To qualify as an SNP, the variation must be present in at least one percent of the population. There are more than 600 million SNPs in populations from all around the world.

[Related: This 7th-century teen was buried with serious bling—and we now know what she may have looked like.]

The team discovered SNPs that had details about Emperor Wu’s hair and skin color. Historians think he was ethnically Xianbei–an ancient nomadic group mostly located in present day Mongolia and northern and northeastern China.

“Some scholars said the Xianbei had ‘exotic’ looks, such as thick beard, high nose bridge, and yellow hair,” study co-author and Fudan University bioarchaeologist Shaoqing Wen stated in a declaration. “Our analysis shows Emperor Wu had typical East or Northeast Asian facial characteristics,” he adds.

With the SNP data and Emperor Wu’s skull, the team rebuilt his face as a 3D image using open-source Blender software. The software is based on the average depth of soft tissue of modern Chinese individuals. They also used the HIrisPlex-S system, which “forecasts externally visible human traits using 41 SNPs.”

The genetic data showed that he has brown eyes, black hair, and “dark to intermediate skin.” His facial features were also similar to those from parts of Northern and Eastern Asia today.

“Our work brought historical figures to life,” study co-author and Fudan University paleoanthropologist Pianpian Wei stated in a declaration. “Previously, people had to rely on historical records or murals to picture what ancient people looked like. We are able to reveal the appearance of the Xianbei people directly.”

Emperor Wu passed away in 578 at the age of 36. Some archaeologists believe that he died of an illness, while others say the emperor was poisoned by his rivals. Analysis of his DNA using a genetic database called Promethease, shows that he was at an increased risk for stroke, which could have contributed to his death. According to the team, finding aligns with historical records that describe Emperor Wu as having potential symptoms of a stroke–aphasia, drooping eyelids, and an abnormal gait.

[Related: The town was prevented from flooding during monsoons 4,000 years ago by using ceramic pipes..]

The genetic analysis also reveals that the Xianbei people had offspring with ethnically Han Chinese individuals. ethnically Han Chinese individuals when they moved into northern China.

“This is a crucial piece of information for understanding the spread of ancient people in Eurasia and their integration with local people,” said Wen.

In future studies, the team plans to examine the DNA from individuals who lived in ancient Chang’an city in northwestern China. Chang’an was the capital city of many Chinese empires for thousands of years and was the eastern over thousands of years. It was also located on the eastern end of the famed Silk Road–a critical Eurasian trade network from the second century BCE until the 15th Century. The team hopes that the DNA analysis will reveal more data on how migration and cultural exchange unfolded in ancient China.