Keeping our teeth clean has caused discomfort for a long time many years, with some especially painful techniques historically used to take care of our teeth. Two 4,000-year-old human teeth excavated in a limestone cave in Ireland contained a large amount of the bacteria that result in tooth decay and gum disease. The genetic examination of these well-preserved microbiomes shows how changes in diet influenced our oral health from the Bronze Age to today. The research is outlined in a tooth decay study released on March 27 in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution Dental plaque from ancient times has been intensely studied, but.

very few complete genetic codes from oral bacteria in teeth before the medieval era have been found. This means that scientists have limited information on how the human mouth’s microbiome was impacted by changes in diet and by events such as the spread of farming about 10,000 years ago. Bacteria that eat sugar and produce acid

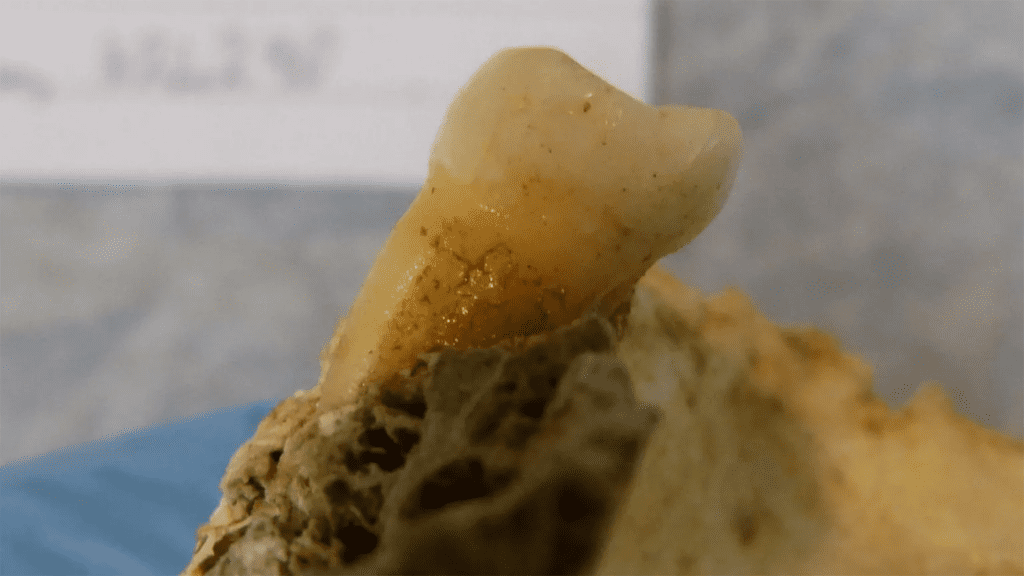

teeth belonged to the same male individual

Both of the who lived in present day Ireland during the . The teeth contained the bacteria that cause gum diseases and the first Bronze Agehigh quality ancient genome from

Streptococcus mutans ). This oral bacterium is one of the major causes of tooth decay. (S. mutansis very common in modern human mouths, but is very rare in the ancient genomic record. One potential reason why it’s so sparse may be

S. mutans how the bacterium produces acid . The acid decays the tooth, but also destroys DNA and stops the dental plaque from fossilizing and hardening over time. Most ancient oral microbiomes are found inside these fossilized plaques, but this new research focused directly on the tooth.Vikings filed their teeth to cope with pain

[Related: Another reason why.]

may not have been present in ancient mouths may be due to a lack of sugary environments for it to thrive in. S. mutans loves sugar and an increase of dental cavities can be seen in the archaeological record after humans began to grow and farm grains. However, the more dramatic increase occurred over the past few centuries when S. mutans sugary foods became significantly more prevalent The disappearing microbiota hypothesis.

The examined teeth were part of a larger skeleton found in Killuragh Cave, County Limerick, by the late

Peter Woodman of University College Cork . Other teeth in the cave show advanced dental decay, but there wasn’t any evidence of any caries–or early cavities. A single tooth turned out to have a ton of“We were very surprised to see such a large abundance of mutans sequences.

in this 4,000 year old tooth,” study co-author and Trinity College Dublin geneticist Lara Cassidy S. mutans said in a statement . “It is a remarkably rare find and suggests this man was at high risk of developing cavities right before his death.”Killuragh Cave in Ireland where 4,000 year-old skeletal remains were uncovered. CREDIT: Sam Moore and Marion Dowd.

DNA. While the S. mutans DNA was plentiful, other streptococcal species were mostly absent from the tooth sample. This indicates that the natural balance or the oral biofilm had been altered– S. mutans outperformed the other bacteria types.mutans According to the team, the research provides further evidence for the

theory that the microbiota is disappearing. . This concept suggests that the microbiomes of our ancestors were actually more varied than our own today. Additional proof for this concept came from the two genomes ofTannerella forsythia T. forsythia () that the team reconstructed from the tooth.T. forsythia still exists and leads to “The two sampled teeth contained quite different strains of gum disease.

T. forsythia ,” said study co-author and Trinity College Dublin PhD candidate Iseult Jacksonin a statement . “These strains from a single ancient mouth were more genetically different from one another than any pair of modern strains in our data set, despite these modern samples coming from Europe, Japan, and the USA. This is interesting because a decrease in biodiversity can have negative effects on the oral environment and human health.Changing genes and mouths

Both reconstructed genomes revealed drastic changes in the oral microenvironment

over the last 750 years . One lineage ofT. forsythia has become dominant in global populations in recent years, which is an indication of a genetic event called a selective episode. This occurs when one strain of bacteria quickly increases in frequency due to a specific genetic advantage. The T. forsythia genomes that emerged particularly after the Industrial Revolution acquired genes that helped them thrive in the mouth and cause disease. Bronze Age cauldrons show our historical fondness for meat, dairy, and sophisticated cookware

[Related: also had evidence of recent expansions in lineages and changes in gene content that coincide with the.]

S. mutans popularity of sugar. However, modern populations have remained even more varied than S. mutans T. forsythia , including some significant divisions in theevolutionary tree that predate the genomes discovered in Ireland. The team believes that this is driven by differences in the evolutionary factors behind the diversity of genomes in these bacteria types. S. mutans is very skilled at exchanging genetic material across strains,” said Cassidy “This allows a beneficial innovation to spread across

“S. mutans lineages, rather than one lineage becoming dominant and replacing all others. S. mutans Both of these disease-causing bacteria have undergone significant transformations from the Bronze Age to today. However, it’s the very recent cultural changes, such as increased sugar consumption, that seem to have had a disproportionate impact.

Too little sugar and too much acid can make identifying traces of tooth decay difficult.