Earlier in this month, author Percival Everett put on formal attire to go to the Oscars with his spouse, writer Danzy Senna.

First-time filmmaker Cord Jefferson, who adapted Everett’s 2001 novel “Erasure” to create the film “American Fiction,” won for best adapted screenplay and gave an inspiring speech that was one of the evening’s high points.

“I like the film a lot, and I respect the fact that it's not my novel. Cord Jefferson used my novel to make his film,” says Everett. “And that’s his job.”

But don’t expect to see Everett at future Hollywood events, as he is not known for seeking the spotlight.

“We did go, and there’s no need to ever go again,” he says with a laugh, adding that he had a “fine” time. “The attention to the work is nice, but … it was hard to sit through. But at least during the commercial breaks, you can wander outside.”

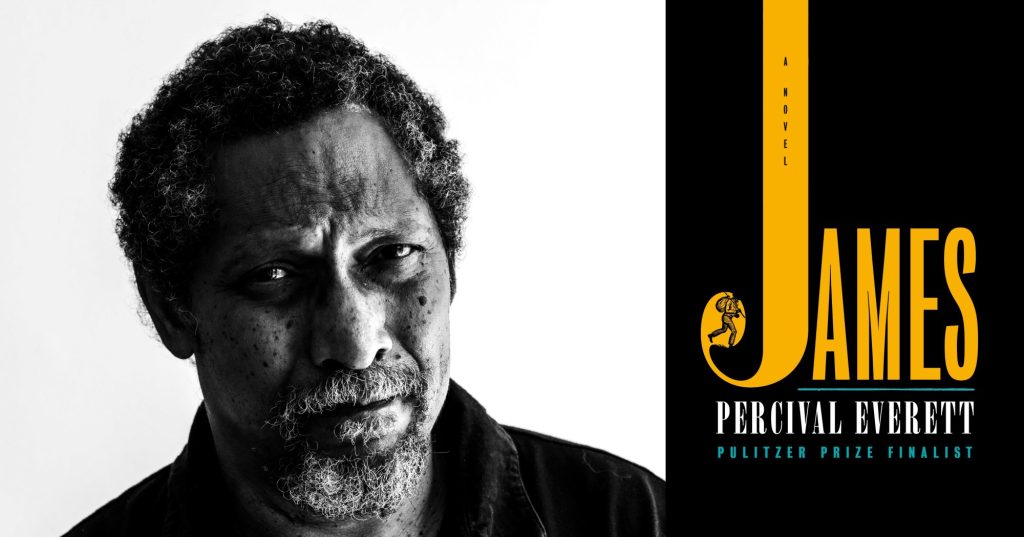

One of the country’s most respected authors and the Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Southern California, Everett’s work ethic is well-known: He's written over 30 books, and his most recent novels — “Dr. No,” “The Trees,” and “Telephone” — have been nominated for various awards including the Pulitzer Prize, the Booker Prize, the NBCC Award for Fiction, and more. (And he still manages to paint, fish, and play guitar.)

When we chat on Zoom about his just-released new book, “James,” Everett is casually dressed and sitting in his home office in South Pasadena surrounded by books, gear, and musical instruments. In the book, which may be his best yet, the story of Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is told from the perspective of the enslaved character Jim instead of Huck Finn.

In Everett’s version, Jim — or as the character writes when he puts pencil to paper, “James” — is revealed to be a more intricate and caring character: He’s a thoughtful and affectionate parent, a teacher and thinker, a builder and fixer of most things, and a self-taught reader and writer (through his secret visits to Judge Thatcher’s library). He is also a determined man cautious of the ways in which slavery not only deprives the enslaved of their physical freedom and safety, but also how the cruel practice aims to hinder intellectual and emotional freedom, too.

Throughout our conversation, Everett gave considerate, humorously wry responses as we talked about the book, Twain, “The Andy Griffith Show,” and more. (And just to be clear: Although this was our first conversation, our partners previously worked at the same college and know each other.)

This discussion has been shortened for brevity and clarity.

Q. Was ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ a book you had strong feelings about? What drew you to writing your own version?

Well, you know, it has a legendary status in the literary world. It’s a book we are familiar with even if we haven't read it in full. I read an abridged version as a child, which didn't impress me at all.

I really like Twain. I didn’t enjoy ‘Tom Sawyer’ at all, but I adored ‘Roughing It,’ I was a fan of ‘Life on the Mississippi,’ and there was another one that was just crazy, ‘The Mysterious Stranger,’ that no one talks about, ‘The Diaries of Adam and Eve.’ Really funny stuff.

So, much of my humor was influenced by Twain, and then when I was older, I did read the complete ‘Huck Finn’ and even as a teenager, the portrayal of Jim, naively on my part, is problematic. It’s not until I was a little more mature and understood Twain and his position in the culture that I could grasp that portrayal. Maybe not excuse it completely, but understand it.

Q. Can you discuss that a little more?

The book really is America wandering through this landscape, trying to figure itself out. That’s what Huck is. Huck is the typical adolescent American. And I don’t mean 12-year-old American; I mean, 12-year-old America, that young country trying to come to grips with race. And so it really is an important text.

It’s the first book where it’s about a person who is subjected to slavery and not about slavery. And so with that in my head, I just wondered if anyone had written it from Jim’s point of view. Since then, I found out that there is a short story — I still haven’t seen it – about Jim after the novel. But I was shocked to find out that no one had written one — and then I realized I hadn’t thought of it either, so I couldn’t really blame anybody.

Q. One of the most remarkable things about the character Jim is how you evoke his concern for his family, for others, and for Huck.

Even in ‘Huck Finn,’ the only positive father figure — well, maybe Judge Thatcher, peripherally — that Huck has is Jim. I suppose in some readings it can be reduced to ‘companion,’ but the only positive male role model for him is Jim.

Q. People — like Tom Sawyer, Pap or other adults in his life — are often telling Huck things that aren’t true, but Jim, who is narrating and relating his own story, is possibly the only person telling the truth.

I hadn’t thought about that so much, but I like that take on it. For Jim, there’s something at stake in his being able to explore ideas in a literary way. At the other end of that, for him, is a freedom that he can’t physically enjoy.

Q. Can you talk about the elements you introduced to the story and what you decided to leave out?

Well, since in the novel, Jim and Huck are separated a lot of the time, those were easy. And since it’s from Jim’s point of view, the dangers inherent in any of those scenes where they are together are different, as well as that it’s through the eyes of an adult rather than a child.

This is not a complaint at all about Twain, but I’m thinking less to entertain than I am to interrogate. And so when I have a chance to work with [con men characters] the duke and the dauphin, my mission is different from Twain’s.

Q. Your book is affecting, harrowing and, it has to be said, often extremely funny. How did you navigate all those elements?

I’m pathologically ironic, and I think any humor that I use is a result of that irony. I would be a terrible comedian. I’m no good at making up jokes, but just observing an absurd world.

Remember the show “The Andy Griffith Show”? It can be tiring if you watch a lot of it, but one thing I liked about the show was that it doesn't have any jokes. All the humor comes from the story, except for physical humor from Don Knotts. It was a good lesson to see that.

Q. Why did you decide to have Jim hallucinate debating the philosophers Locke and Voltaire?

The Declaration of Independence, written by the philosopher Thomas Jefferson, who believed in equality among men but supported slavery, is ironic. He was a figure of the Enlightenment like Voltaire and Locke.

Q. You said you have a tradition of writing a book where you started it. Where did you start and write this book?

I was at the coffee table. Yeah, that’s pretty much where it happened.

Q. Earlier, you said you don’t remember your books, and I wonder if that’s similar to a reader’s experience — how we can be invested in a book only to find later that it’s hard to recall details of what happened in the story. Is that like what you’re describing?I think that’s probably close to it. Sometimes when people remind me of things in my novels, it takes me a while to catch up. Sometimes it’ll be vivid, other times it’ll be completely new, and I kind of like that. I especially like when they have ideas about what it means that I never thought of. I immediately take credit for it: “This is a great idea; of course, I meant that.” [laughs]

Q. Is that disorienting?

Oh, no. It’s just fascinating. People see their own worlds; the work doesn’t exist without a reader and meaning can’t happen without a reader. I wasn’t writing it to convince myself of anything. Lord knows why I was writing it, but there it is.

Q. So after you’ve written it, you no longer need to try to control it.

I can’t control it, so why worry about it? I suppose I could go hang out in front of bookstores and explain things to the six people who leave with my book. [laughs]

Q. If you do, please call me. That sounds great.

Anything I say about one of my works can be completely disregarded.