This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine,

In late July, numerous brown bears gather at Brooks Falls, in Katmai National Park and Preserve on the Alaska Peninsula, to feast on sockeye salmon leaping upstream to reach their spawning grounds.

Mesmerized, I stand with a group of tourists on a wooden viewing platform, watching as dominant bears claim spots at the top of the falls, and young subadults patrol the banks for leftover carcasses. A 350-kilogram male submerges in the frothy pool of water beneath the falls, emerging with a salmon 10 seconds later. He grasps the fish between his two front paws, resembling a prayer, then devours it whole.

I’ve always longed to visit the bears of Brooks Falls, a popular destination for up to 37,000 visitors each year. But I’m here now for a much smaller, less well-known mammal—one that will take center stage as the sun sets and the dim, fading light summons a surge of mosquitoes.

Meet Myotis lucifugus, commonly known as the little brown bat. Or, as bat researcher Jesika Reimer affectionately refers to it, “the flying brown bear.” Little brown bats share many similar physiological and behavioral traits with Ursus arctos. Both are slow-reproducing mammals that can live for many decades in the wild. Both feed intensely during the summer and autumn months to prepare for a winter in torpor, a state of metabolic rest. Yet the little brown bat weighs less than 10 grams.

“They’re so small and we’re so oblivious to them,” reflects Reimer. “That’s why I love bats so much.”

Several hours after observing the bears, I meet Reimer a short distance from the falls at a log cabin that houses US National Park Service staff in Brooks Camp. She turns on her headlamp and inspects a mist net she’s set up outside—a black mesh so fine it’s nearly invisible, strung between metal poles that stand six meters tall. Somewhere above us, as many as 300 female little brown bats jostle in the cabin’s warm, secure attic where they have gathered for the summer to give birth and raise pups—an arrangement known as a maternity colony. Tonight, at the 58th parallel, with just four to five hours of true darkness, Reimer aims to catch a few in hopes of solving a long-standing mystery.

Perhaps because bats so easily escape human notice, scientists have little knowledge about where those that live at this far northern edge of the species’ range spend their time during the winter months. To find some answers, Reimer is leading the first-ever gene-flow study of maternity colonies in Alaska outside of the state’s more temperate southeastern arm. How interconnected are these Myotis lucifugus populations, she wonders? And where, exactly, are they hibernating?

We hear a fluttering from the cabin’s awning, and Reimer’s handheld acoustic monitoring device detects a fast series of echolocation sounds—high-pitched sounds that bats emit to navigate and find food. Not long after, one gets caught in the net. With great accuracy, Reimer gently untangles the animal. It squints up at us, its snout looking squeezed and its black ears nearly as big as its head. It’s smaller than I had imagined, just nine centimeters long. Reimer turns the bat over in her palm and gently blows on its light brown fur. I glimpse a pink nipple. “Lactating female,” Reimer says, then stretches the bat’s black wings wide on a table. “Their wings are basically their hands,” she explains, noting that there are almost exactly the same number of joints in a bat’s wing (25) as in a human hand (27). Then, she carefully attaches a silver ID band to the bat’s forearm and uses a small tool to extract a tiny amount of tissue—genetic material for her study—from each wing.

As she works, she invites several bystanders to take a closer look. “They’re actually so cute,” one exclaims. Another takes a slow-motion video as Reimer releases the bat into the night sky. She says that engaging citizens in research is a vital part of her work to change the dominant narrative about bats, a mammal that many people fear unnecessarily—and one that faces serious conservation threats.

A fungal disease called white-nose syndrome is decimating bats across North America, killing an estimated 6.7 million since it was first detected in upstate New York in 2006. The fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, has been documented in bats in 40 US states, and its known northern spread includes eight Canadian provinces. It thrives in the cool, damp conditions of hibernacula, caves and hollows where hundreds to thousands of bats huddle together for the winter, creeping onto their ears and noses and across their wings, causing lesions and dehydration. Infected bats stir out of torpor to groom themselves, spending precious fat reserves, and often starve to death once they’re depleted.

Recently, in places where the fungus was first detected, subpopulations with genetic resilience are starting to bounce back, but the situation is still dire. The mortality rate of bats with white-nose syndrome can reach as high as 90 to 100 percent, depending on the colony. Canada listed little brown bats as endangered in 2014 due to drastic declines in eastern provinces. The United States is considering listing the species as well.

It’s not a question of if, but when white-nose syndrome will arrive in Alaska, potentially threatening little brown bats here, too. Reimer hopes that the gene-flow study will put biologists one step closer to locating the bats’ winter hibernacula. That way, when white-nose arrives, they will be better able to monitor—and manage—the impacts.

Reimer has dedicated more than ten years to specializing in the study of bats, She was attracted to studying bats because of their evolution to occupy specific ecological roles, such as pollinating particular flowers, spreading fruit and tree seeds, and controlling insect populations.

Bats have a wide variety of characteristics. They are the only mammals capable of true flight and are found on every continent except Antarctica. There are over 1,400 documented species of bats, ranging from large fruit bats to the tiny bumblebee bat. Bats play vital roles as pollinators for over 500 plant species, benefiting natural habitats and human agriculture.

Despite their remarkable qualities, bats unfairly suffer from a reputation as bloodthirsty, rabies-carrying rodents, according to Reimer. She points out that less than two percent of wild bats in North America test positive for rabies, which is significantly lower than other animals like foxes. In 2021, only three people in the United States died from rabies contracted from bats.

Even when bats are not feared, they are often ignored. Many scientists and conservation organizations show more interest in charismatic large animals like wolves, humpback whales, and brown bears. However, Reimer prefers focusing on the underdog. She expresses her desire to explore less noticed areas and ask new questions.

Reimer's background includes growing up in Yellowknife, working as a tree planter in northern Alberta, and conducting research in Greenland. She developed her passion for bats while studying ecology at the University of Calgary in southern Alberta, where she examined the diets of bats killed by wind turbines. However, her heart always yearned to return to the North.

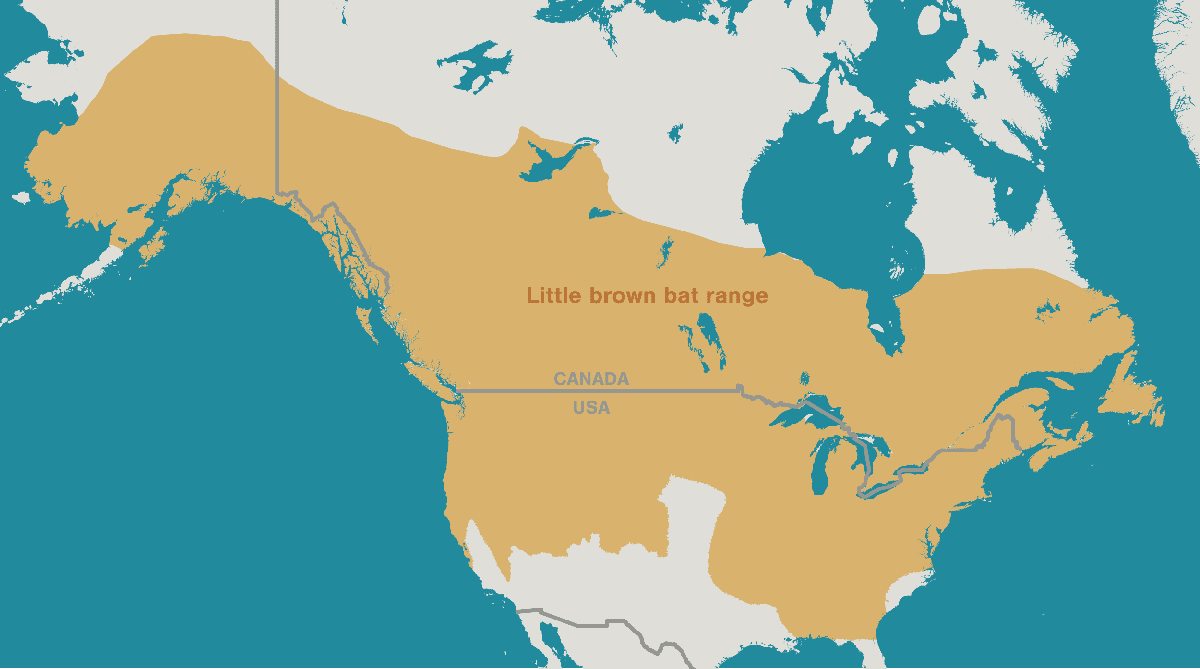

In 2010, a group of cavers discovered a large bat hibernaculum in a cave system located in the boreal forest outside Fort Smith, NWT, where thousands of little browns were overwintering. This discovery provided Reimer with an opportunity to return to her home. She spent several seasons studying bats at their maternity colonies, using acoustic monitoring and capture surveys. Her research revealed that, at the 60th parallel, little brown bats become active at lower temperatures and give birth later than their counterparts in the US lower 48—likely a result of the northern environment. Subsequently, Reimer moved west to accept a research position with the Alaska Center for Conservation Science at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where she began locating and collecting data from maternity colonies in Alaska. than their counterparts in the US lower 48—likely a physical response to the northern environment. Eventually, Reimer migrated west to take a research position with the Alaska Center for Conservation Science at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and she began locating and collecting data from maternity colonies in Alaska. The small brown bat is one of the most common bat species in North America, and can be found in every state, province, and territory except Nunavut, where the forests the bats prefer shrink into tundra. Although there are five other bat species in southeast Alaska, the little brown bat is the only confirmed species north of that area, with a known range reaching as far as the 64th parallel.

The little brown bat is currently the only confirmed bat species in Alaska found outside the state’s southeast region, extending as far north as the 64th parallel.

can a nocturnal, hibernating species thrive in a place where true darkness may last less than two hours on the summer solstice, and colder winters demand more fat reserves? does Brown bears can eat all day and night throughout the summer and fall. However, bats depend on darkness to protect them from predators while they search for food, so they must build up fat stores in short, intense feeding sessions, according to Reimer. They also cannot become too

fat, or they won't be able to fly to their hibernation site when the time comes. Through the use of acoustic monitoring devices to record and analyze feeding frequencies, Reimer has started to understand how the bats manage. For instance, in the Far North, they fly at dusk—what Reimer refers to as “extra-solar flights”—despite being more vulnerable to owls and other raptors. too The cold also presents significant challenges for

Myotis lucifugus in Alaska. Not only can little brown bats get frostbite on the tips of their ears, but food is often scarcer. The species primarily consumes insects, and individual bats can consume their weight in mosquitoes, moths, midges, and mayflies in a single night. They are skilled at “aerial hawking”—scooping insects into their mouths with their tails or wing membranes. When the temperature drops, so does the availability of insects, and little brown bats have adapted to enter torpor as easily as flicking a switch. “If there’s a bad weather event, or no food, bats can save energy rather than go find energy which doesn’t exist,” Reimer explains. Little brown bats in Alaska have also developed a more varied diet compared to southern populations. In 2017, researchers

found that, as well as catching arthropods on the wing, they “glean” them from webs and foliage, adding orb-weaver spiders and others to their menu. With climate change and shifting habitats, including the northward expansion of the treeline, this adaptability could be beneficial. discovered However, there is one thing Reimer has yet to figure out. Since 2016, she has identified more than 25 summer maternity colonies. However, she has not yet found any winter hibernation sites.

Twenty kilometers southeast of Brooks Camp, I follow Reimer down a trail that descends into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. The slopes are densely forested, a sharp contrast to the valley floor, which is covered in pink pyroclastic rock. This is the result of the 1912 eruption of Novarupta, a magma vent at the base of nearby Mount Katmai—this was the largest volcanic eruption in the 20th century.

We enter a spacious grove of birch trees where there's plenty of room to move between the trees or, if you're a bat, to fly. 'Little brown bats like open forest canopies like this one for finding food,' Reimer says. 'Once you understand bat behavior, you start to see their living spaces everywhere. You have to think like a bat.'

The steep bank of the Ukak River gorge in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, Alaska, displays pyroclastic rock formed by the eruption of the Novarupta volcano in 1912. Reimer wonders if little brown bats could be hibernating in the cracks and crevices of the rock.

But Reimer’s hypothesis—and her hope—is that bats here behave differently than their southern counterparts. There’s good reason to think so, based on

recent findings in southeast Alaska by biologist Karen Blejwas . Starting in 2011, Blejwas attached tiny radio tags, weighing 0.3 grams, onto dozens of bats from summer roosts near Juneau, Alaska, in hopes of finding their hibernation spots. In the late fall, she boarded a fixed-wing plane fitted with radio tracking. She flew at sunset, circling where the bats gathered, waiting for one of them to make a move so she could follow. Sometimes she'd get a signal only to have it vanish. 'It was like looking for a needle in a haystack,' recalls Blejwas.Then, three years after Blejwas started her search, her research team struck gold. The first-known Alaska hibernaculum wasn’t a cave with 1,000 bats; it was a small hollow, tucked beneath rocky scree on the side of a steep ridge, with just a handful of occupants.

Since then, Blejwas has found 10 hibernacula in unassuming places: under tree stumps and mossy rubble, in a jumble of rocks, tucked into upended root balls on toppled trees. She set up trail cameras at some of the sites and observed bats swarming outside and entering their hibernation spots. They were all small groups, ranging in size from one to 12 bats.

The cold presents significant challenges for Myotis lucifugus in Alaska. Reimer is currently documenting cases of damaged ear tissue, which could be caused by frostbite.

We come out of the forest and walk along the steep edge of the turbulent Ukak River. Reimer stops and points at something on the other side of the rushing water. I’m not completely sure what she’s looking at. Then, I see it: a series of small openings and fissures running through the volcanic rock wall, just big enough for a bat to seek shelter in.

The sun goes down at 10 p.m. in King Salmon, a small fishing community with 300 residents in Alaska’s Bristol Bay. This is the starting point for visiting Katmai National Park, about an hour-long boat ride from Brooks Falls, and Reimer and I are back for one final examination before I leave, driving through the twilight in a Park Service truck to search for promising locations.

We park next to a group of run-down buildings stacked with fishing buoys. Reimer jumps out to inspect an old storage shed that has “all the elements” of a place where bats would love to roost: it has a high ceiling, an attic, and sun-bleached wooden shakes that bats could easily slip under for shelter. But she only finds a few dried guano pellets. Despite all she knows about bat preferences, she admits that the most reliable way to find a bat roost is when a homeowner calls to complain about one.

Reimer sets free a research bat from her field station in King Salmon.

Yet, Reimer has heard stories of homeowners firing bear spray into their roofs or pouring bleach into their walls; often, they kill entire colonies. Bats aren’t like mice, which can replenish their numbers quickly by having five to 10 litters per year. And more than 50 percent of bat species, including the little browns,

face the risk of steep population decline or extinction over the next 15 years. “Once you exterminate a bat colony, that colony isn’t coming back,” says Reimer. “It would be like killing all the bears at Brooks Falls. The following year, there won’t be any bears.” So as Reimer works on her surveys, she also works on the public, hoping to help more people learn to appreciate bats. She tells homeowners who report colonies that bats aren’t likely to chew insulation and wires like mice. She also makes sure they know that the bats will depart by late August. She recruits homeowners to participate in efforts to count bats as they emerge for the night—one of the ways researchers get an idea of populations—or to help with one of her capture surveys. Seeing little browns up close and learning about their unique adaptive biology and behaviors often changes people’s minds about them, she says: “They start to care about ‘their’ bats.” And once the bats have left for the winter, homeowners can seal off their homes so that the bats find a more appropriate place the following year.

Before it gets completely dark, Reimer gets a strong feeling about the three-story Park Service apartment building where we’ll stay for the night. We go back and set up mist nets, then arrange her field equipment on the back of the truck in the parking lot. It doesn’t take long before we hear the familiar sound of wings from the building’s awning. A dark shape flies down, curves back up, dives again, and lands gently in the net. It’s one of the last for this particular study—another unintentional helper in the effort to ensure its species’ future in the Far North.

This article was initially published in

Hakai Magazine and is reprinted here with permission Active in daylight during the Arctic summer and hibernating during the long winter nights, Alaska’s small brown bats are a unique population..