The Hudson River used to be among some of the most polluted rivers in the United States. Following many years of laws about the environment and people working to make changes happen, wild animals like bald eagles, bears, and whales are being seen more often in New York. The Hudson is also an important home for American eels that move from one place to another, and now they are getting some help from ordinary people who are interested in science.

For the first time, this science information from ordinary people will be taken as official information put into the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s (ASMFC) checked eel stock report. Since 2008, the Hudson River Eel Project has relied on close to 1,000 ordinary people who are interested in science giving their time each spring to catch, count, and let go about two million young American eels.

“What I love about the eel project is it takes another step deeper toward volunteers actually becoming scientists and thinking about research methods and the research questions we’re trying to answer,” Chris Bowser, project leader and Cornell University environmental scientist and educator, said in a statement.

[Related: How eels might get a ride to Europe.]

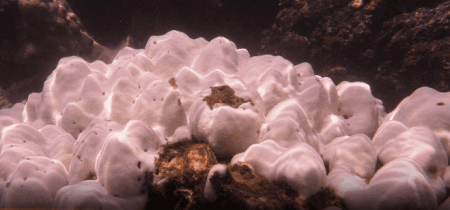

The project has several watching places between Troy south towards New York City. People count and follow the young eels who are often called glass eels, since they are see-through at this part of life. Their information helps make decisions about taking care of the environment, since the species is an important part of the food web.

An eel’s life

American eels start to be alive about 3,700-miles miles southeast of the Hudson in the salty Sargasso Sea. When they are babies, the eels are shaped like thin leaves and they move north to the freshwaters of the Caribbean islands, South America, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic coast from Florida to Canada.

To get to New York, the young eels use a ride on the Gulf Stream water. They change into their see-through 2-inch long glass eel state when they get to the mixed waters of coastal estuaries. They move into the 150-mile Hudson River tidal estuary every year from February through May. Glass eels then serve an important form of food for bigger living things.

When they move into freshwater streams and creeks, they develop color and change into tiny adults called elvers. The elvers become not ready to make babies yellow eels in their next grown-up stage, changing to a brown, dark green, gray, or mustard yellow color. These older eels become top living things that help keep the environment in balance by eating fish, water bugs, and animals like a shrimp.

They may stay yellow eels for five to 30 years before they are ready to make babies and change into silver eels. The grown-up silver eels then go back to the Sargasso Sea to make babies and likely die.

Ordinary people interested in science stepping in

Small rivers and mixed waters can make it harder for the young eels to move, which gives those learning about them a chance to catch, count, and let the eels go to get an idea of how many there are that can help with bigger science studies.

“When done right, ordinary science can be very helpful because it can greatly make bigger an agency’s or a biologist’s range, and also have data spread out over time with tens of thousands of volunteer hours over the years,” said Bowser. “We have tried to collect data that is as strong as what’s been done at the agency level.”

[Related: How to become a citizen scientist and when to let professionals handle it.]

ASMFC approved the latest data in August 2023, partly because of the eel project’s strong data quality-check processes. Partners from Cornell University and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation created these standards to ensure that their protocols were easy to follow, standardize, and could be repeated each year. According to Bowser, the citizen scientists are all well trained and their eel count numbers and procedures are examined.

Eels have been discovered in every waterway that connects with the Hudson River, including urban rivers such as the Saw Mill River in Yonkers, the Fall Kill Creek in Poughkeepsie, and the Poesten Kill creek further north in Troy. They also swim in rural areas, including the Hannacroix Creek in New Baltimore and Black Creek in Esopus.

“The widespread geographic diversity of eels means that you also have widespread diversity of volunteers,” said Bowser. “Different ages, different socioeconomic backgrounds, different experiences.”

Monitoring at the Fall Kill Creek site in Poughkeepsie for this migration season started in late February. There, local high school students and their teachers walk into about two feet of water around nets and traps that are set up along the shoreline where the glass eels swim. Another group may be counting and weighing the eels, while others gather air and water temperature data.

‘Every single dam is a potential barrier’

Chemical pollutants, overfishing, climate change, habitat loss and human-made obstructions like dams have all have taken their toll on the eels over the years. “Every single dam is a potential barrier for eels on their migration route,” Bowser said.

To help address this, the eels that the project counts are released past at least the first known barrier to their migration, whether it be a road, culvert, or dam.

If you are interested in

taking part in a citizen science project like the Hudson River Eel Project, go to citizenscience.gov to find something nearby. Roughly 1,000 Hudson River Eel project volunteers catch, count, and release about two million juvenile American eels per migrating season.