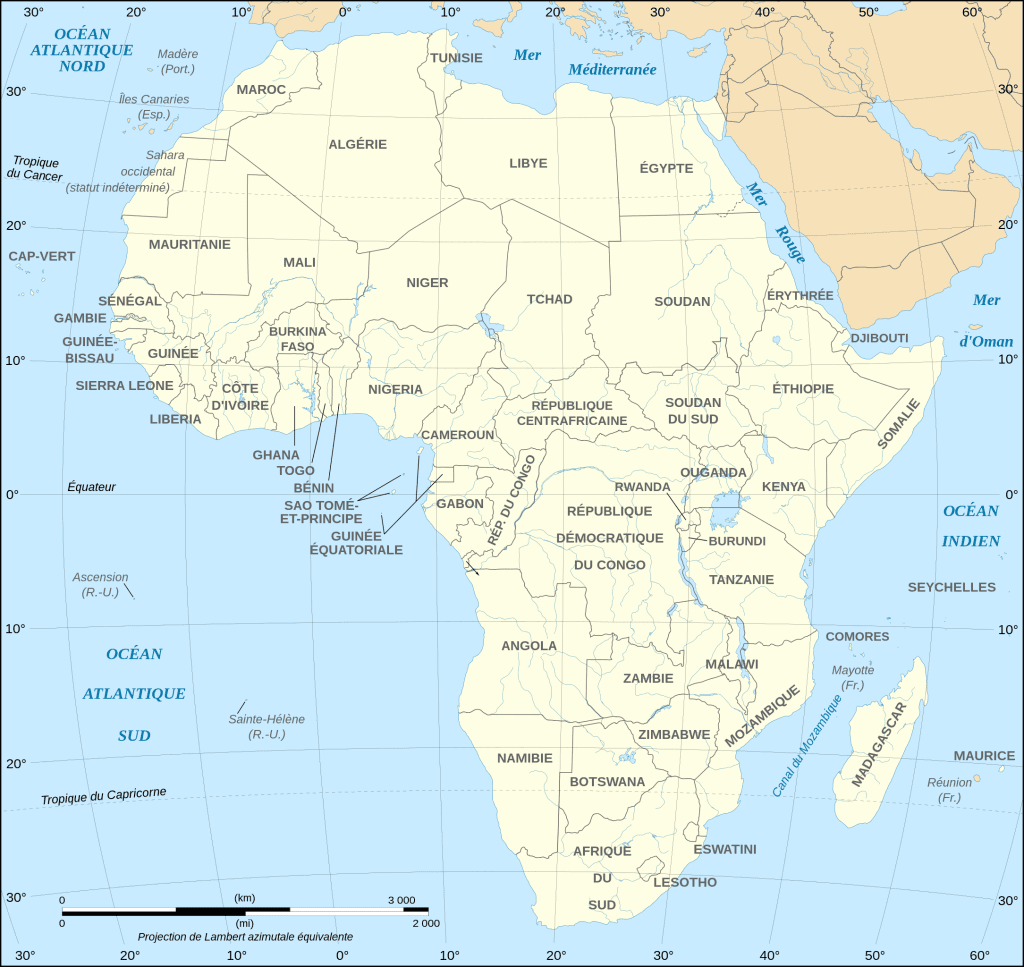

When you look at a map of Africa, you'll see many suspicious straight lines, right angles, and diagonals. Many were taught in school that the borders of African states look like this because that’s how the colonial powers drew them, dividing the territories among themselves. It’s similar to how states in the U.S. are separated, but that’s a different colonial story for another time.

Imagine a group of old white men with beards and top hats, a cigar in one hand and a ruler in the other, arguing over who gets what. That’s sort of the mental picture conjured by this tragic partitioning. It may sound silly, but there are real and deep-seated consequences to this partitioning that are felt to this day, as many ethnic people found themselves in a different country overnight. Wars have been fought over this, sometimes leading to genocide.

But this picture isn’t entirely accurate. A new study by political scientists from Emory University, Washington University, and Loyola University challenges the conventional wisdom that Africa’s international borders were drawn entirely arbitrarily by European colonial powers. Instead, it argues that border formation in Africa was a dynamic process influenced by on-the-ground realities, particularly precolonial political frontiers and major geographical features.

What’s the real story of Africa’s borders?

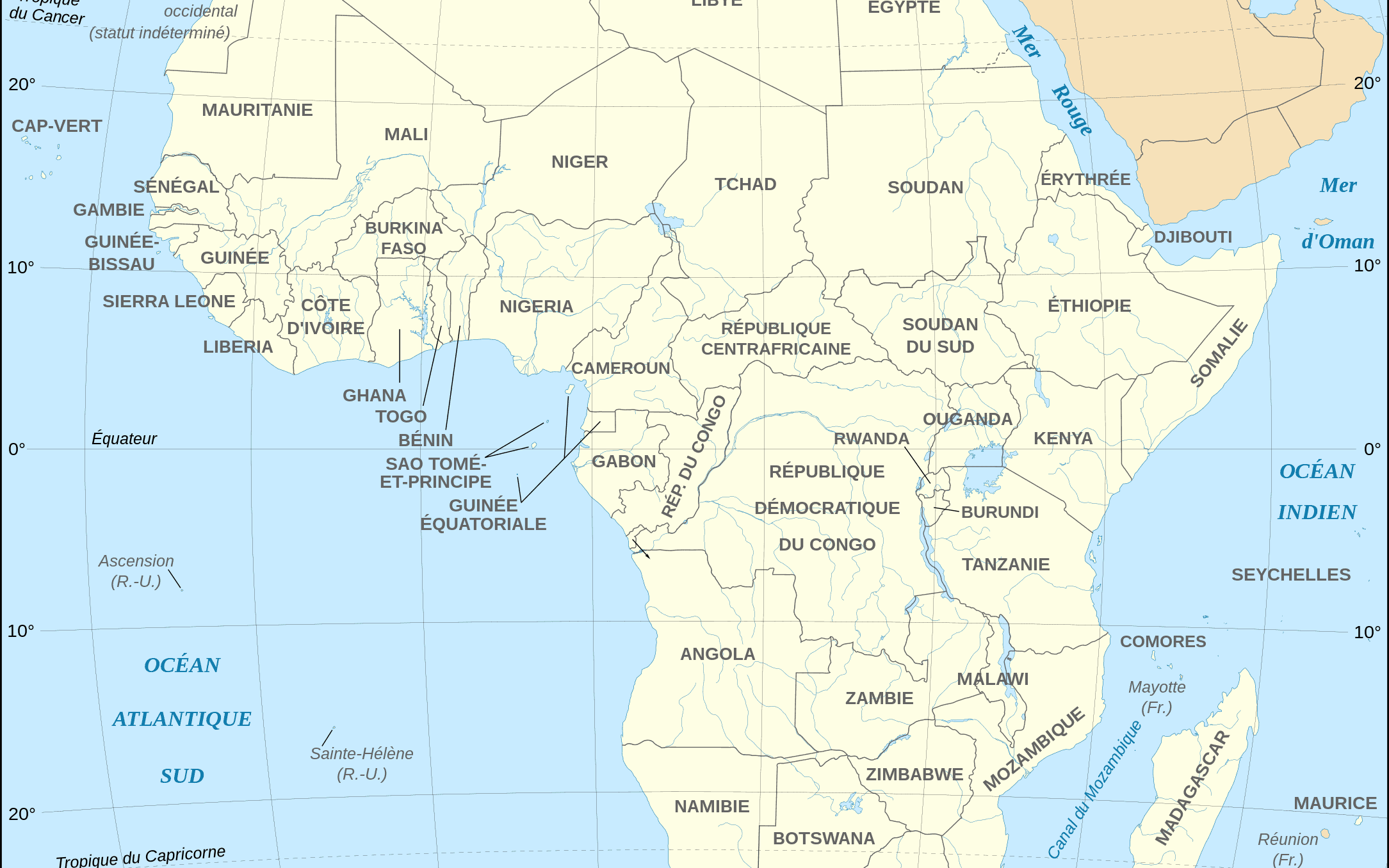

Despite Europeans’ limited knowledge of Africa when most current international borders on the continent were established at the Berlin Conference in 1884-85, evidence suggests they nevertheless made some effort to sketch them out sensibly. This was not out of compassion for the people of Africa or out of some sense of foresight that doing otherwise would escalate tensions. Naturally, it was out of practical self-interest. Berlin Conference in 1884-85, evidence suggests they nevertheless made some effort to sketch them out sensibly. This was not out of compassion for the people of Africa or out of some sense of foresight that doing otherwise would escalate tensions. Naturally, it was out of practical self-interest.

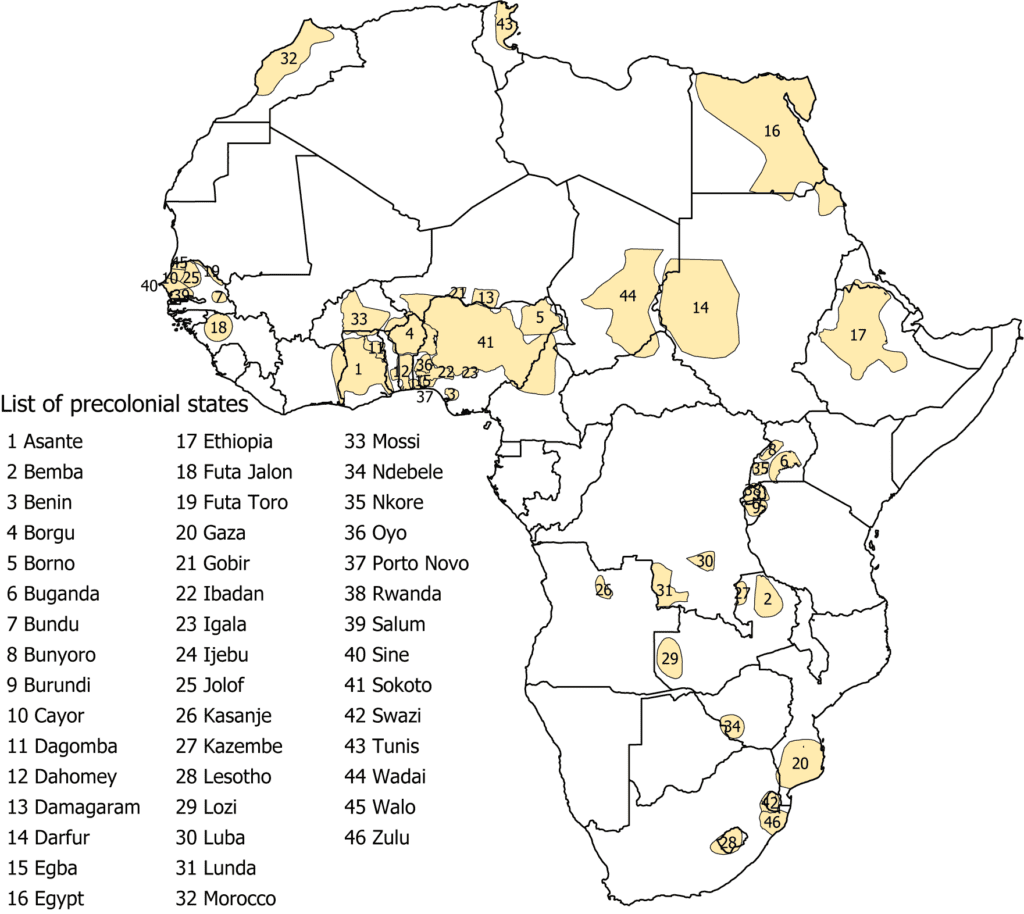

In order to maximize their territorial acquisition and access to resources, powers such as Great Britain, France, Germany, and Belgium, all sent delegates to secure treaties from indigenous peoples or their supposed representatives. They also examined local conditions such as rivers and terrain, as well as historical state frontiers, the researchers wrote. This means that Africans, or at least their leaders, were more involved in influencing the border formation process than most people think.

The authors used two original datasets for a quantitative analysis of African borders. They employed grid cells to statistically analyze the likelihood of border segments coinciding with rivers, lakes, and the frontiers of pre-colonial states. This analysis reveals that borders are more likely in areas associated with these features. For instance, major water bodies were often used as focal points for borders, and straight-line borders were mostly confined to areas lacking discernible local features.

They also conducted a thorough analysis, gathering treaties, diplomatic histories, and observations of causal processes for each bilateral border. They discovered proof that historical boundaries directly influenced the placement of many African borders established later by Europeans.

In general, the study revealed that historical political boundaries had a direct impact on 62% of all bilateral borders. This shows that European powers, while aggressively pursuing their territorial ambitions, often somewhat respected existing political and territorial boundaries.

The intricate dividing issue

Although they found that Africa’s borders were not random, or at least not completely so, the researchers acknowledge the significant social effects of colonial division.

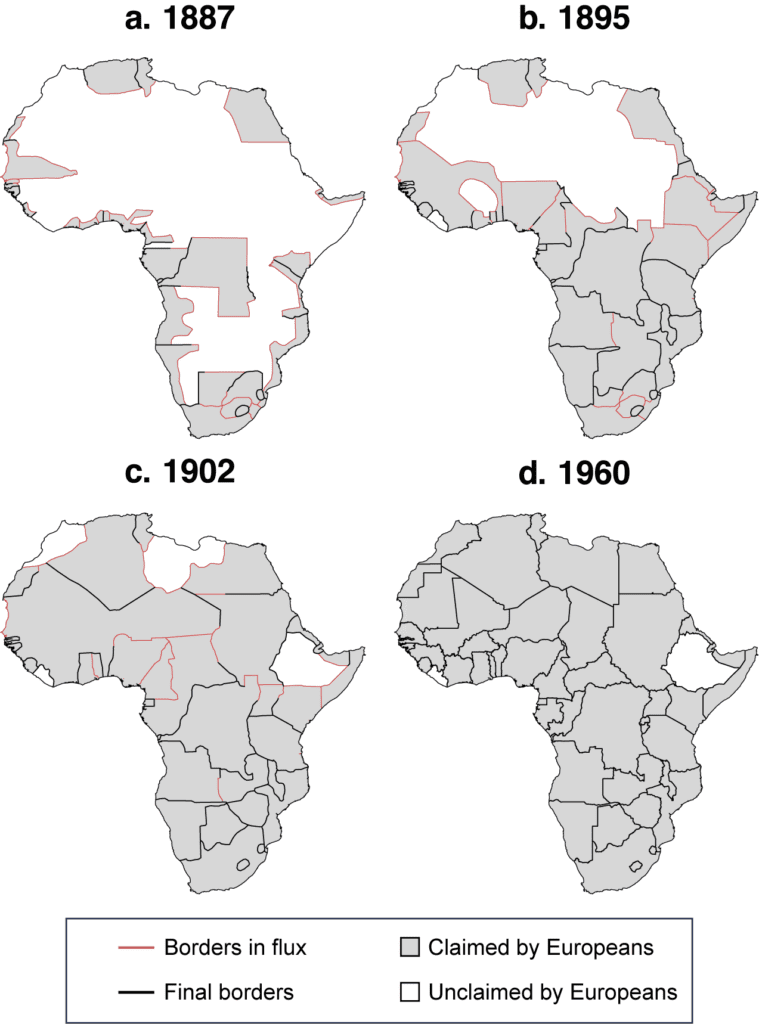

“African colonial borders are less aligned with ethnic geography than borders elsewhere, and they frequently dismembered ethnic and cultural groups across international boundaries. Such borders, even when they incorporated local features, clearly created deleterious human consequences. Our contribution with regard to dismemberment is to demonstrate that which groups were partitioned followed a systematic process, contrary to existing assertions.”

“Areas with precolonial states were rarely dismembered because incorporating their territorial limits created an agreed-upon method for self-interested Europeans to allocate territory. Furthermore, frequent migration and intermingling among peoples of different ethnicities, cultures, and languages ensured that any regional system that enshrined fixed territorial borders would divide groups with fractured polities or decentralized institutions,” the authors wrote in American Political Science Review.

The researchers also emphasize another important point. They argue that pre-colonial states, often fragmented into small tribes, were too small in both size and number to serve as the basis for the colonial and subsequent post-colonial African states we see today. Even if the European powers had created the borders with more thoughtfulness, that still wouldn’t have resolved the numerous problems and negative consequences we witness today.

“The conventional wisdom on Africa’s “bad borders” suggests the following counterfactual: taking as given the general contours of the European colonial occupation and externally created states, certain negative outcomes would have been less likely if Europeans had been more conscientious when determining the location of borders. Our evidence suggests strongly that this counterfactual is wrong. Imposing any set of fixed borders would have suffocated precolonial states within larger colonial states (at least without creating hundreds of states) and dismembered decentralized groups.”

“Although colonial states in Africa were largely artificial with respect to historical antecedents and geographic considerations, the borders between these states were not. Africa’s borders reflect a negotiated and systematic process that scholars and popular accounts have largely overlooked and misunderstood.”