Dinosaur fossils get most of the hype, but uncovering plant fossils is crucial for understanding the long-gone ecosystems of the past. In a plant find that’s definitely worth the buzz, a team of researchers have found the oldest known fossilized forest. The remains of this ancient forest are embedded in sandstone along the coast of southwest England and date back about 390 million years ago. These fossilized trees are roughly four million years older than the previous record holder–the Gilboa fossil forest in New York. The findings are detailed in a study published February 23 in the Journal of the Geological Society.

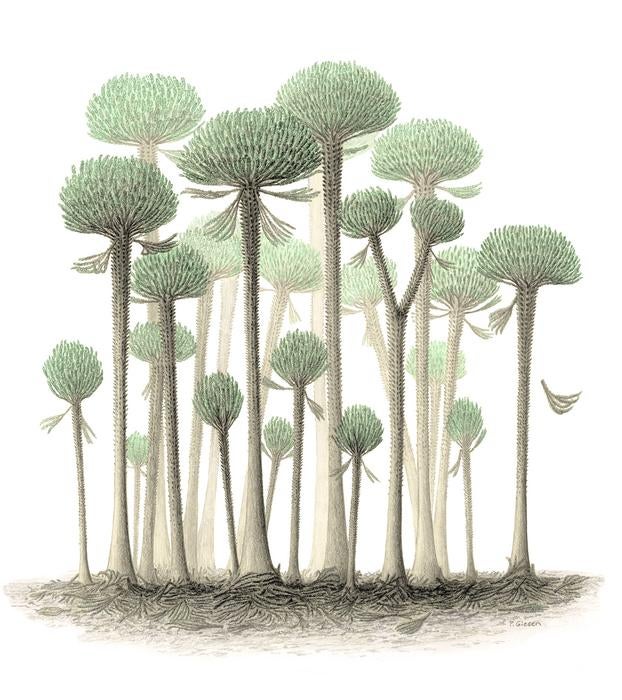

The fossilized trees were uncovered in a rock embedded in the Hangman Sandstone Formation of Somerset and Devon, which dates back 393 million to 383 million years ago. At a quick glance, they look a bit like palm trees. These Calamophyton trees were actually a “prototype” or an earlier evolutionary version of the relaxing tropical trees we know today. Instead of solid wood, their trunks were thin and hollow. They also had branches that were covered in hundreds of twig-like structures instead of broad shady leaves.

The tallest of these trees were only about 6.5 and 13 feet tall, compared to their descendants which can reach towering average heights of 30 to 50 feet. As Calamophyton grew, the trees shed their branches, and this vegetation likely supported the invertebrates living on the forest floor hundreds of millions of years ago.

The forest dates back between 419 and 358 million years ago, during the Devonian Period. This was when life on Earth began its first really big expansion from the sea up onto the land. By the end of the Denovian, the first seed-bearing plants and earliest land animals were well-established.

[Related: Feast your eyes on exquisite fossils from an ancient rainforest (and more).]

“The Devonian period fundamentally changed life on Earth,” study co-author and University of Cambridge geologist Neil Davies said in a statement. “It also changed how water and land interacted with each other, since trees and other plants helped stabilize sediment through their root systems, but little is known about the very earliest forests.”

During the Devonian period, this part of the Devon and Somerset coasts weren’t attached to the rest of England. It was connected to parts of present-day Germany and Belgium and part of an ancient continent called Laurentia. This continent was near the equator and had a dry and warm climate. Similar Devonian fossils have been found in Belgium and Germany.

“When I first saw pictures of the tree trunks I immediately knew what they were, based on 30 years of studying this type of tree worldwide,” study co-author and University of Cardiff palaeobotanist Christopher Berry said in a statement. “It was amazing to see them so near to home. But the most revealing insight comes from seeing, for the first time, these trees in the positions where they grew. It is our first opportunity to look directly at the ecology of this earliest type of forest, to interpret the environment in which Calamophyton trees were growing, and to evaluate their impact on the sedimentary system.”

Older trees existed elsewhere on the plant, since plants first started to grow on land about 500 million years ago. However, this is the earliest known example of a forest where trees were growing close together en masse. While digging into these high sandstone cliffs, the team identified fossilized plants and plant debris, fossilized tree logs, traces of roots, and sedimentary structures. This area was likely a semi-arid plain with small river channels spilling out from mountains to the northwest during the Denovian.

[Related: Fossilized plants give us hints about what ice age forests may have looked like.]

“This was a pretty weird forest–not like any forest you would see today,” said Davies. “There wasn’t any undergrowth to speak of and grass hadn’t yet appeared, but there were lots of twigs dropped by these densely-packed trees, which had a big effect on the landscape.”

This was also the first time that tightly-packed plants could grow on land. The amount of debris that the Calamophyton trees shed built up in the rock layers, and affected the way that the rivers flowed within the landscape. According to the study, this is the first time that the course of rivers could be affected in this way.

“The evidence contained in these fossils preserves a key stage in Earth’s development, when rivers started to operate in a fundamentally different way than they had before, becoming the great erosive force they are today,” said Davies. “People sometimes think that British rocks have been looked at enough, but this shows that revisiting them can yield important new discoveries.”