Something is consuming hydrogen and organic molecules on Saturn’s moon Titan, and the recipe matches astrobiologists’ theories about possible methane-based life. Granted, there may be other chemical explanations — it’s just that no one knows what they are yet.

New data from the Cassini spacecraft show hydrogen is disappearing near Titan’s surface. What’s more, scientists have not been able to find acetylene, an organic molecule that should be pretty abundant in the moon’s thick atmosphere.

All this fits very nicely with a theory from NASA astrobiologist Chris McKay, who proposed five years ago that microbial life on Titan could breathe hydrogen and eat acetylene, producing methane as a result.

Scientists emphasize that the findings are not proof of life, and there’s plenty of work to do before non-biological causes can be ruled out. Scientific conservatism suggests that a biological explanation should be the last choice after all non-biological explanations are addressed,” says Mark Allen of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in a NASA release.

The good news is that even if life is ruled out, the non-biological explanations are still interesting. According to previous studies, hydrogen should be distributed pretty evenly throughout Titan’s atmosphere. But it’s disappearing at the surface.

“It’s as if you have a hose and you’re squirting hydrogen onto the ground, but it’s disappearing,” says Darrell Strobel, a Cassini interdisciplinary scientist based at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., who authored a paper published in the journal Icarus.

It’s possible that the hydrogen is combining with carbon on Titan’s surface to produce methane. But Titan is too cold for that to happen quickly enough to account for all the missing hydrogen. An unknown mineral could be the culprit, meaning scientists may have found a new substance previously unknown to exist on Titan.

The explanations for the dearth of acetylene are equally puzzling. The hydrocarbon should form abundantly in icy aerosols in Titan’s atmosphere, but it’s not there. It’s possible that sunlight or cosmic rays are transforming the acetylene into more complex molecules that would fall to the ground with no acetylene signature, according to NASA.

It’s also possible that chemical reactions are transforming acetylene into benzene (which Cassini did observe on Titan’s surface), but that would require a catalyst, which hasn’t been identified.

There’s one more thing: Cassini observed an organic compound with the benzene that scientists have not been able to identify.

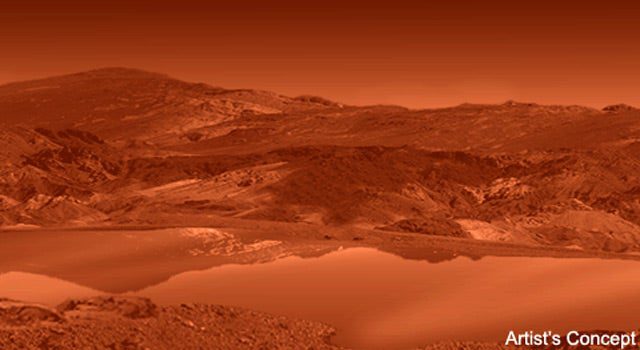

Cassini has several more Titan flybys in which to gather data — in fact, the craft is set to fly within 2,000 miles of Titan’s surface this afternoon, to make infrared scans of the moon’s north polar region. The region includes Kraken Mare, the largest lake on Titan, which covers a greater area than the Caspian Sea on Earth. If methane-based microbes do live on Titan, there’s a good chance they would live in just those sort of lakes.