Caleb Harper is the founder of CityFARM at the MIT Media Lab, a program dedicating to exploring the future of agriculture through “food computing.” Popular Science spoke with him about his Thanksgiving plans for this year.

What are you eating and/or growing for Thanksgiving?

My work involves growing food in environments that we can control with a computer. Imagine a box in which we can create a climate by controlling things like carbon dioxide, oxygen, temperature, humidity, and light. We have sensors running in that box to monitor what’s going on inside, and the computers adjust the variables to the levels we want.

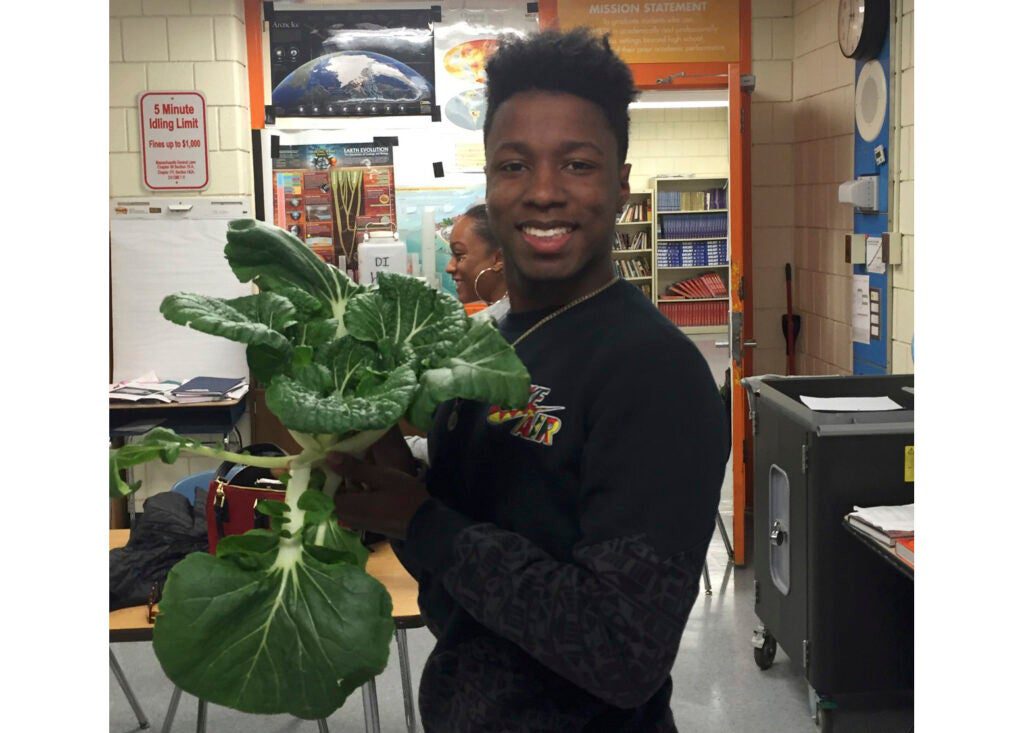

I currently have seven of these little boxes in seven schools throughout Boston. Students from 7th through 11th grade are growing vegetables like mustard greens, kale, basil, and radishes. This week we harvested a bunch of vegetables so the students could take them home for Thanksgiving.

It turns out about 90 percent of what we like about the food we eat comes from the environment. People often claim things like the “best strawberries come from Mexico” or the “best tomatoes come from New Jersey,” but really the best strawberries and tomatoes come from whatever climates produce the size, sweetness, and colors that we like. Since we’re coding the climate, we can code the flavor that comes out on the other end. It’s like we’re creating little worlds.

We’re also growing plants in big boxes about the size of shipping containers, which we use for research. We’re harvesting those for Thanksgiving as well, and donating vegetables to local food shelters in the Boston area, including Pine Street Inn, Haley House, and Daily Table.

How do you know what “codes” a perfect strawberry?

A big part of my research is figuring out correlations between environmental variables and how plants express things like taste, color, and texture. We’re trying to create a model of the plants and understand how they express different features over time.

The goal is to make this open-source — imagine a Wikipedia full of “climate recipe” files that people can upload and download. Let’s say I’ve grown some really good broccoli and I upload a digital recipe for how to grow it. You might see “Caleb’s broccoli” online, download that digital recipe to the plant box in your house, and put a broccoli seed in. You’ll have almost 100 percent success in growing broccoli that has the same characteristics mine had.

We see kids already doing this in schools. They’ll e-mail each other climates they’ve created and say, “Hey, this is what we did to make the basil taste really sweet or grow super tall.” Then other kids might tweak that recipe and upload it again, saying “Hey, we changed one thing and it made the basil more spicy.”

You can get really specific with the parameters you’re controlling, from the minerals that are in the water to the temperature of the water relative to the temperature of the air. For each plant we might be monitoring somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 to 30 variables.

What does this mean for the future of agriculture?

First of all, we can use the little food computers to help a lot more kids understand the production of food. With a digital interface for growing plants, more people can be farmers — you don’t have to be a farmer’s daughter or son, you can be an electrical engineer and contribute to global food solutions. Producing next-generation farmers is one of the most exciting things to me.

On a more practical side, you can produce a lot more food where it’s consumed. We’re experimenting with warehouse-sized boxes that could allow people who live in cities to grow a substantial amount of nutritious food. In the next 10 to 15 years, city-dwellers might get 30 percent of their food from where they live in, whereas right now it could be zero to five percent depending on the city. By eliminating shipping, we’d be cutting down on carbon emissions and food waste.

There are also applications for space. This is the type of technology that could be used by folks at SpaceX or Lockheed Martin who are interested in colonizing Mars. There are already growing experiments on the International Space Station that’s similar to the work we do.

But ultimately, this technology would be good in a lot of places, like the Middle East or Northern Africa, where you can’t currently grow a lot of food. Qatar imports over 90 percent of its food and Japan imports about 60 percent. If you watch the movie The Martian, you’ll see that the landscape looks a lot like the landscape in New Mexico. I think the movie itself was shot in Jordan. As much as this technology could be important on Mars One, it could be as important in Dubai.