Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once wrote that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Clarke was thinking a bit too narrowly, though. Really, any sufficiently technical and jargony science is often indistinguishable from magic–or for the Olympics, pseudoscience.

The newest sensation sweeping the Games is cupping, an ancient bloodletting practice originally used to purge chi. Nowadays, it’s typically extolled as a device to remove “stagnant blood, expel heat, treat high fever, loss of consciousness, convulsion, and pain.” There’s no scientific consensus as to how bursting capillaries with heated cups accomplishes this, but it can certainly have some medical effects … like possibly necrosis.

Nevertheless, the real heydey of Olympic quackery is long gone. For a while, from the 1904 Olympics’ Anthropology Days for “savage” races, on through the 1936 Games, which saw doubt that the black Jesse Owens could outpace the Aryan ideal, the principles underlying Olympics-related scientific theory was just eugenics pseudoscience.

As fascination with proper breeding waned, biomechanics started becoming the common denominator of Olympic progress. The high jump, alone, went through seven popular techniques before settling on the whimsically named Fosbury Flop in 1968, as the most efficient. External factors became more important, too. Running outfits evolved from three-quarter length combos to form-fitting duds. Carbon fiber bikes began popping up in the ’80s, alongside mens’ speedos–a far cry from the old baggy two-piece suits. Then, in ’92, Speedo debuted the s2000 suit that cut drag by 15 percent, which would later give rise to the 2008 LZR suit that would be banned for its effectiveness.

But as the LZR suit showed best, Olympic boundary-pushing has changed. As human physiology has raced closer to its limits, advances in engineering and technology around the athletes have played a more dominant role in keeping the plateauing rates of broken records trudging forward. So, it’s not surprising that athletes will look anywhere, including pseudoscience, for that personal edge.

Cupping may be making headlines, but by no means is it the extent of modern Olympic pseudoscience. Since 2008, the games have popularized kinesiology tape, which, somehow, “alleviates discomfort and facilitates lymphatic drainage” using slight lateral tension on the surface of your skin. Only, it doesn’t.

In addition to cupping, some Olympians are turning to acupuncture, which, although it has no evidence behind its use to treat disease, has been shown to reduce pain, (physical pain, at least)–regardless of where the needles are stuck. In other words, the placebo pain reduction of wanton needling is nearly as effective as precision pricking.

Then there’s the paleo diet, acclaimed by swimmer Amanda Beard, which comes with a good principle: “eat what we’re made to eat, and we’ll be healthier.” Except, hunter-gatherer diets came in lots of different types, with the general macronutrient split ranging from 19-35 percent for protein, 22–40 percent for carbohydrate, and 28–58 percent for fat. Not to mention things like widespread lactose tolerance show that our digestive systems have evolved alongside our diets.

Even icing sore muscles, a widely accepted practice, is often abused as an unscientific recovery panacea before going back into the game–though the Olympics are hardly the only culprit. Most evidence to date suggests that using it as a stopgap before returning to activity could potentially do more harm than good.

There’s more, to be sure, including Olympic endorsements of vitamins, which nutritionists generally contend are unnecessary for most Americans–and which decades of mortality rate tracking for at least 429,000 individuals has demonstrated are actually more likely to be counterproductive to health.

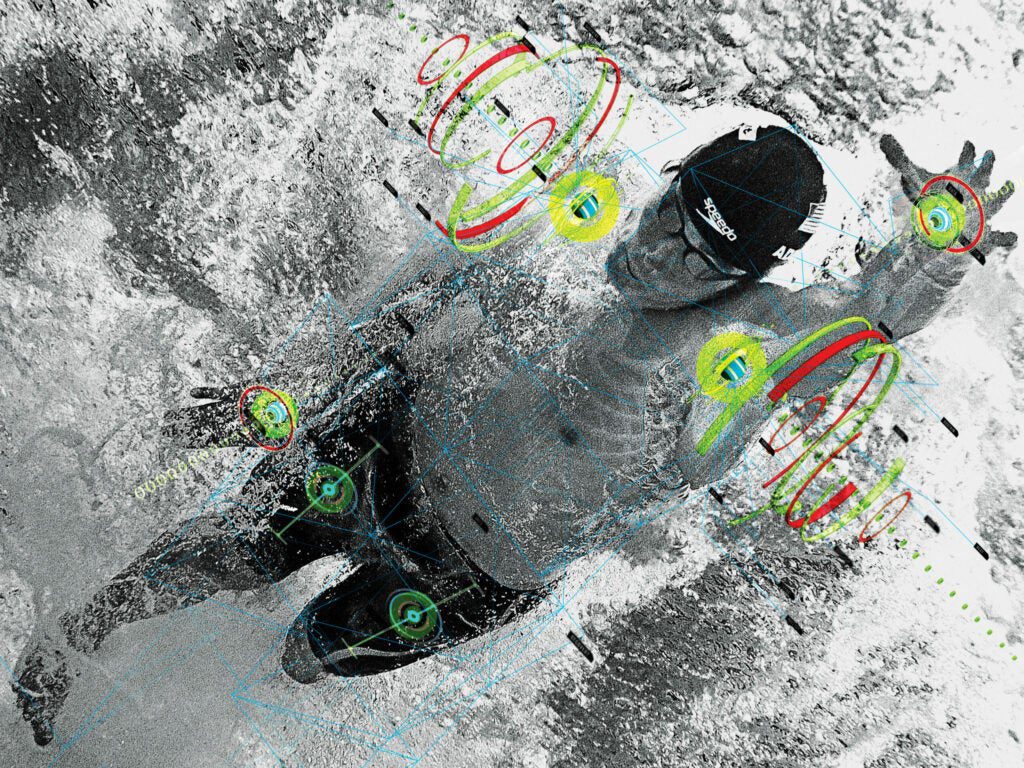

Yet it’s hard to fault athletes. Through the last few games, more so than ever before, records have fallen thanks to small-scale engineering, from silica nanoparticle-loaded racquets to carbon nanofiber golf clubs, and Big Data analytics that digitize athletes, model their movements, catalog performances, and help formulate strategies.

When the best arrows in Olympians’ quivers are among science’s most abstract, jargonistic, and near-mystical, it’s not surprising they’d find pseudoscience indistinguishable–or perhaps even more plausible due to its seeming simplicity.