Last summer, as sweet crude oil gushed unabated into the Gulf of Mexico, the overriding emotion was one of frustration. It wasn’t just directed at the well owner, BP, or at rig-builders Transocean and Halliburton, or even the government and its difficult-to-understand oil flow estimates. The inability to shut off the well was one thing — but why, in an era of nanotubes and autonomous robots and invisibility cloaks, couldn’t we just clean it up?

To learn more about each team, check out our gallery of the competition and the various designs.

Sure, skimmer ships, containment booms and dispersants deployed immediately, aiming to capture oil gushing from the blown well beneath the destroyed Deepwater Horizon rig. But week after frustrating week, the best available technologies failed to make much of an impact. But some people saw opportunity in this disaster — a chance to prove a new idea, or maybe build upon an old concept. The Wendy Schmidt Oil Cleanup X Challenge, under the auspices of the X Prize Foundation, encouraged competitors to design new oil-removal technologies that would dramatically improve the state of the art. Today in New York, we found out just how far some friendly competition and a tidy sum can push the technological envelope.

Nearly 400 applicants were narrowed down to 10 finalist teams, who were invited to test their techniques at the nation’s oil spill test bed, the Department of the Interior’s Ohmsett facility at the Naval Weapons Station Earle in Leonardo, N.J. The minimum criteria to be eligible for the prize: a technology capable of an average oil recover efficiency (ORE) of more than 70 percent—that is, the mixture extracted from the water had to be 70 percent oil—and an oil recover rate (ORR) of 2,500 gallons per minute. That’s roughly twice what the oil cleanup industry’s best technology can currently recover. The leading team was promised a $1 million reward, while second and third place would receive $300,000 and $100,000 respectively.

The winners did more in a handful of months than private industry had done in the two decades since the Exxon Valdez disaster.This morning in New York, just minutes before revealing the winners of the Wendy Schmidt Oil Cleanup X Challenge, Schmidt herself made what would prove to be the understatement of the event: “This is a powerful return on a relatively modest investment,” she said knowingly. A few minutes later we would find out just how right she was. Second place winner NOFI of Norway demonstrated technology that extracted 2,712 gallons per minute with an ORE of 83 percent. But audible gasps went up when the winning numbers hit the presentation screen. Team Elastec/American Marine had blown the competition out of the water, recovering 4,670 gallons per minute at efficiencies averaging 89.5 percent.

In other words, Elastec/American Marine nearly doubled the gallons-per-minute requirement for the X Prize. But perhaps a better way of looking at it is through the lens of the state-of-the-art. In just one year’s dedicated time, NOFI found a way to double the efficiency of the industry’s best available surface oil skimmers. Elastec/American Marine tripled it, doing more in a handful of months than private industry had done in the two decades since the Exxon Valdez disaster.

It wasn’t easy. Throughout August and September, the teams huddled at Ohmsett for 10 days each, removing oil with skimmers, booms, spinning axial devices and even a “shaver,” testing amid calm seas and turbulent waves. Hurricane Irene briefly interrupted testing, and lent an air of harsh reality to NOFI’s efforts.

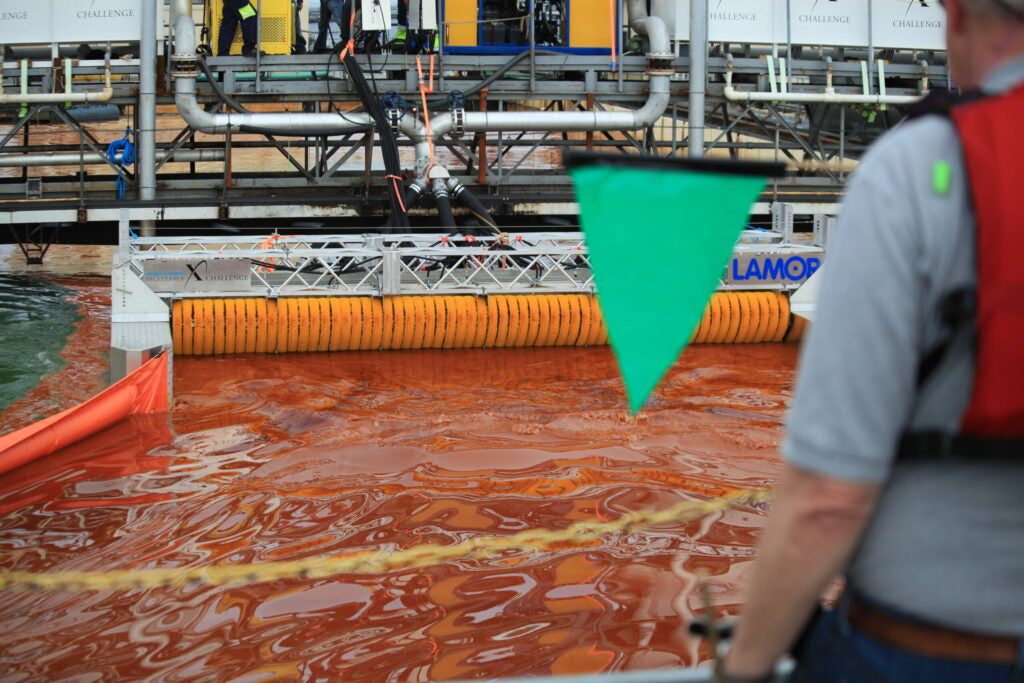

Each team completed a minimum of six tests, three in calm conditions and three with waves. Once the team was ready to go, the judges would wave a green flag to give the go-ahead, and Ohmsett staff would start the stopwatch, open the valves and let the group get to work.

Team Lamor Gets the Green Flag

A referee waves the green flag to give the go-ahead to Team Lamor of Finland during the Wendy Schmidt Oil Cleanup X Challenge.

“The team would be on the bridges operating their system — they’re turning on pumps, monitoring performance, and letting the judges know they are ready,” said Cristin Dorgelo Lindsay, vice president of Prize Operations for the X Prize Foundation, who managed the competition. “It is a really finely tuned dance… it is like getting into a test tube and being shaken about. It was very stressful.”

The competitors included a retired police inspector; two generations of one family; a tattoo artist; a former pro basketball player and several other entrepreneurs and inventors. Each team had its own judges, who consisted of industry reps, Coast Guard officials and marine conservation experts, examining each system according to various criteria, she added.

“It was a little bit like summer camp. People from all over the world get to come and hang out at this Navy base in New Jersey,” Lindsay said.

But unlike summer camp, the work being done there was anything but carefree. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill and the weeks and months of unchecked pollution of gulf ecosystems placed a new urgency on finding ways to remediate waters fouled by man-made disasters, and the X Prize offered the financial impetus as well as the benchmarks for success that drove the search for better technologies.

“Nobody thought about an oil spill such as the Gulf oil spill, so nobody was asking for this,” Elastec/American Marine team leader Don Johnson said. “Nobody was asking for 2,500 gallons per minute.” Things like the X Prize are critical to pushing technology forward, Johnson said, because when there’s no industry demand for a technology and no customer to buy it, it doesn’t get built. And given the nature of disasters like Deepwater Horizon, the time when demand peaks—during an actual oil spill—is not the time to be developing and testing new technologies. During the Deepwater Horizon spill Johnson and his team were out on the gulf corralling oil with last-gen technologies rather than building new technologies in the workshop, he notes. They would have been better served if the new technology had already been on the shelf.

To tackle these kinds of challenges, we need to be proactive rather than reactive, Johnson said. Deepwater Horizon serves as a stark reminder of that. And just in case that’s not clear, there’s $1 million to drive the point home.

Deepwater Horizon Skimming Operations

A high volume skimming system skims oil from the Gulf of Mexico near Venice, La., April 28, 2010. Skimmers like these helped remove some of the oil leaking from the blown Macondo well last summer, after some 4.9 million barrels of oil spilled into the Gulf. After the spill, Wendy Schmidt, wife of Google CEO Eric Schmidt and president of their family foundation, sponsored an X PRIZE Challenge to come up with a faster, more efficient way to separate oil from water.

Ohmsett Facility

This summer, teams from the U.S., Norway, Finland and the Netherlands spilled oil in a massive saltwater pool off the New Jersey shore and tried their best to clean it up. Tuesday in New York, one team will win a $1 million X PRIZE purse for their efforts. The Ohmsett facility in Leonardo, N.J., features North America’s only full-scale oil cleanup testing facility. The 666-foot-long, 65-foot-wide, 11-foot deep pool holds 2.6 million gallons of saltwater. A wave generator creates waves up to 3 feet high, as well as irregular “harbor chop” waves. A bridge alongside the pool serves as a simulated boat, capable of towing oil removal equipment at speeds up to 6.5 knots. Teams can observe their progress from a control tower, and video cameras capture oil recovery above and below the surface.

Team Crucial

Louisiana-based Crucial Inc. manufactures several types of skimmers, including mop, disc, drum or weir (dam) designs, as well as sorbents and additives. The company makes an absorbent coating material that can be applied to its drum and disc skimmers, boosting their recovery rates by up to 500 percent, according to the company. Crucial’s oil recovery efficiency ranges from 87 percent to 82 percent, depending on the gallons-per-minute rate. Before the challenge, the company’s coated spinning drum achieved the highest pure oil recovery rate in Ohmsett history.

Team OilWhale

This Finnish design is a competition veteran, already participating in several cleanup challenges in the U.S., France, the UK, Dubai, Norway and Russia. Plus its dual jet ski-style design definitely looks like the most fun. The system works by capturing water and oil together, so dispersion and mixing is kept at a minimum, unlike methods that use brushes and skimmers. The recovery system looks like a catamaran, with a gate that captures the oil-water mixture. The oil floats to the top and is removed without any pumps, according to the company. Then gates in the hull bottom release the water, leaving the oil inside the reservoir. The system can be pushed in front of a tugboat, towed by a barge or incorporated into a purpose-built ship, the company says.

Team Elastec

A veteran of oil spill cleanup, this Illinois‐based team built a new grooved-disc skimmer that improves on its existing technologies. According to the company, their first eureka moment came by accident: While working on a small oil spill several years ago, Donnie Wilson asked colleague Jeff Cantrell to throw him a 5-gallon bucket. The wind caught it and it fell into the oil slick, where it started to spin. The two noticed that the oil stuck to the side of the bucket, and their barrel skimmer was born. The company also makes fire-resistant booms, which were used to skim and burn oil recovered in the Deepwater Horizon aftermath. Elastec tested a new skimmer design in the X Challenge, a product it was already building after three years of testing and development. The grooved disc has some of the highest recovery rates of any skimmer, according to the company.

Team Koseq

This Dutch team makes a suite of V-shaped containment booms, which channel oil into a skimmer system. Its newest design, the Victory Oil Sweeper, was inspired by the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The sweeper channels surface oil into a skimmer mounted at the junction of the V’s two arms. The arms can be set apart at various degrees, enabling the whole system to fit inside narrow channels or large areas. It is either pulled alongside a large vessel or pushed in front of a small tugboat, according to the company.

Team Lamor

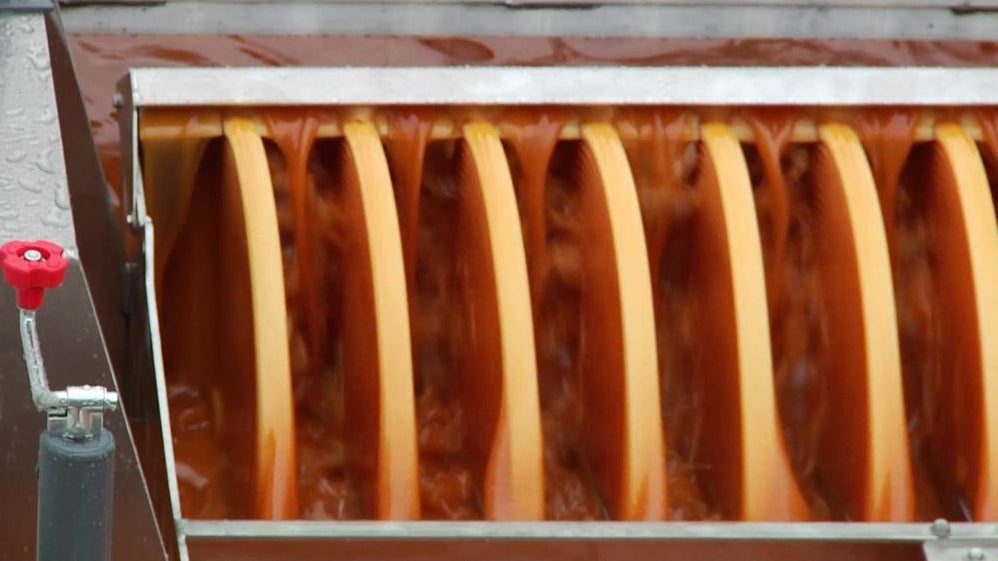

One of several existing oil cleanup firms to join the competition, Lamor Corp. (which stands for Larsen Marine Oil Recovery) was heavily involved in cleaning up the Deepwater Horizon spill, and tested one of its newest products for the X Challenge. The Lamor Squalus, which is Latin for shark, is inspired by sharks’ smooth, fast movement through water, according to the company. It consists of an oil-attracting brush wheel and brush belt, which skim through the water to pick up oil. The Squalus brush belt is shaped like a shark’s head, which will dampen waves as well as separate oil from water, according to the company. Lamor, which hails from Finland, has been building oil cleanup technology since 1982. The new design is intended for high-capacity oil removal, the company says.

Team NOFI

Just as oil recovery workers would in a real-life spill, team NOFI, one of the two Norwegian teams, had to deal with an unexpected variable — Hurricane Irene. The competition halted as the storm pummeled the Atlantic coast, but the spill testing facility held up just fine, enabling NOFI to test its Current Buster system after a five-day delay. NOFI uses a flexible V-shaped boom, towed alongside one vessel or between two of them. The surface boom corrals the oil toward the V junction, where a separator removes the oil from the water. The company’s separator yields a thicker layer of oil than other recovery systems, which is more efficient to reuse or burn off once the oil is captured. NOFI has been making the booms since 1995 and says they can collect and separate oil at speeds up to 5 knots.

Team OilShaver

Fishery trawl tech is the inspiration behind this Norwegian design — team leader Ingvar Huse was trained as a fisherman and has spent 30 years working in fisheries science in Europe, Africa and the U.S. The design includes a pair of parallel floating pontoons a couple feet apart and connected to a sealed floor, which is made of neoprene and polyester. The tunnel-shaped device sits at a 45-degree angle into oily water. The floating oil (and a small amount of seawater) is trapped and “shaved” off the surface, before it starts mixing with water due to the turbulence of the collection device. The collection unit looks like a large toilet seat. Meanwhile, a weighted slit along the bottom of the neoprene floor lets the dense water escape, while oil is pumped into a vessel for storage.

Team Voraxial

Enviro Voraxial Technologies built the Voraxial Separator after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. The Separator uses centrifugal forces to recover the oil. The machine is mounted to a vessel with conventional oil skimmers, and the skimmed mixture is fed into a chamber. An impeller mixes the fluids at high speeds, and the oil and water are separated by densities. Centrifugal forces form a column of oil at the chamber’s center. When the chamber opens, water flows back into the sea, while the oil stays on the skimmer ship. One model, the Voraxial 8000, can process 172,000 barrels of oil and seawater every day, according to the company.

Team PPR

Formed directly in response to the Deepwater Horizon spill, PPR uses an open-water skimmer design. The horseshoe shape seen here shepherds the oil so it can be collected. The design is based on materials already used in other maritime applications, and it can be scaled to various situations, according to the company.

Team Vor-Tek Recovery Solutions

This team may have some of the most unique members — team leader Ashley Day is a former college and pro basketball player, and team member Fred Giovannitti is a tattoo artist. The team was initially inspired by the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and developed the Marine Particle Skimmer system to collect small plastic particles from the open ocean to be recycled into raw materials. The Deepwater Horizon rig exploded as Day was drumming up interest and investors, sparking greater interest in the MPS’ ability to remove oil from water. After the spill, Vor-Tek developed the EEL, or Emergency Extraction Line, specifically to deal with oil. It consists of a series of floating horizontal modules extending out from an oil platform or support vessel, like vertebrae in a spinal column. It works in concert with a weir boom setup, which alters water flow. The system includes a pipeline running through the modules, which brings in oil and water to be separated onboard a vessel.