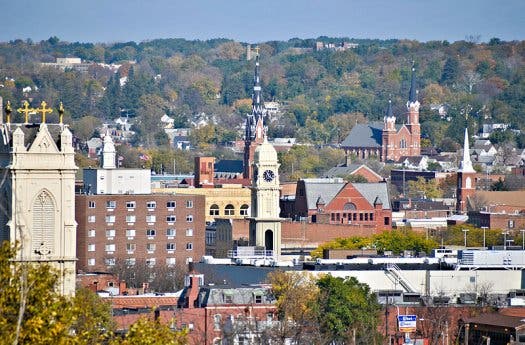

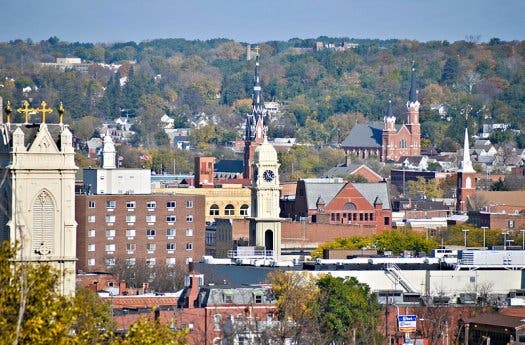

The city of Dubuque, Iowa is a quite and clean city, housing a population of 60,000, making it the 8th largest city in the state. If you happen to pass through this tranquil ville you might get fooled to think this is just another town like any other, however this is not the case – Dubuque is making the transition towards soon becoming the ‘smartest’ city in America. How so? By partnering with IBM, the city council has managed to install a complex array of sensors and launched a sustainable energy campaign among its citizens which will soon allow it to become one of the most efficient urban centers in the country.

I’ve always been concerned about the energy and resource use in this country,” Roy Buol, mayor of Dubuque since 2005, said “It’s almost like people think we have an infinite supply of energy and resources, and we don’t. There are better ways of doing things, but as citizens of the world we don’t have the real-time information so we can make better decisions when we’re using energy and resources.”

During his first year as mayor, Buol managed to have the council on board for a complete turn-around of Dubuque, whose citizens at the time complained about issues like public transit, green space, water quality, and recycling. It was around this time that the city partnered with IBM Research for Dubuque to become the first truly smart city of the nation, bringing sustainable urban infrastructure to a whole different level.

The first step was of implementing a pilot program that replaced the water meters in 300 households with smart water meters that interface with IBM’s technology. Additionally, one thousand more households have been fitted with smart electricity meters for a smarter electricity pilot that is currently underway, along with another program consisting of 250 homes monitored by smart natural gas meters. All these come together and allow for tabulating resource usage, feeding residents and the city real-time data about natural gas consumption.

Thus, citizens willing to enter the program can view exactly what energy goes in and out of their households, easy attainable through an online interface disposed by IBM. This is where the genius of the project lies, by feeding the data directly to the energy consumers, not just to the city counsel or IBM to crunch the numbers in. If you give people the means to investigate power loss, most of the time they’ll take the necessary measures themselves.

“The plan is pretty simple: Give people what they need,” says David Lyons, project manager for Sustainable Dubuque, the larger umbrella initiative that includes the IBM Research partnership. “And they’ve defined that for us. They need information that is specific to their utilization of resources. Not just about how the community or the world uses resources, but ‘how do I use resources?’”

It’s still very early for concrete results to be shown of this innovative experiment, however judging from preliminary data alone, the smart city infrastructure program looks extremely promising for Dubuque and for the rest of the other cities in the world in the future. The smart water metering pilot is already producing hard results: an overall 6.6 percent reduction in the utilization of water that was at least partially driven by an eight-fold increase in the number of households that each–by looking at data–identified and fixed a leak.

Less water waste means less energy waste, which in term leads to exponential increase of efficiency. Word about data regarding the electricity and natural gas side of the project will be unveiled next year, however one might tell it’s already rending results since Dubuque’s city council announced that they’ll expand the project (the water project is already exploding from just 300 households to 3,000 households and 1,000 small businesses).

If it turns out to be a complete success, from all points of view – mainly, sustainability and cost effectiveness – than Dubuque could easily move to any city in the world. You just need to replicate and scale, and have the necessary vision to understand that, in the long run, this is a mandatory solution for an ever growing energy crisis.

“It gives me very strong reason for hope,” Buol says. “I think this creates a very compelling model for other cities to replicate. It won’t be the City of Dubuque or IBM trying to sell what we’re doing: People will be able to see it and they’ll want the same benefits for their citizens and their businesses.”