The National Archives is teaming up with Ancestry, a genealogy company, to convert and organize many records related to the US military, immigration history, and Indigenous communities. The project is expected to take about 5 years, which is 10 times faster than without the Archives’ new tech tools.

Announced on Thursday, organizers plan to put 65.5 million documents online within two years, including military files from World War II and the Korean War, as well as immigration and naturalization reports. This information will initially be on Ancestry’s websites, but will become accessible on the National Archives database.

“The National Archives is the record keeper of the nation, holding billions of stories. Our mission is to preserve, protect, and share those stories with all Americans,” US archivist Colleen Shogan said in an official announcement.

Speaking with The Washington Post today, National Archives’ chief innovation officer Pamela Wright explained that the ongoing digitization efforts make previously hard-to-find information easier for researchers and families to locate. “It’s a geographic barrier for many people,” said Wright, “and making it digital… gives access to the records.”

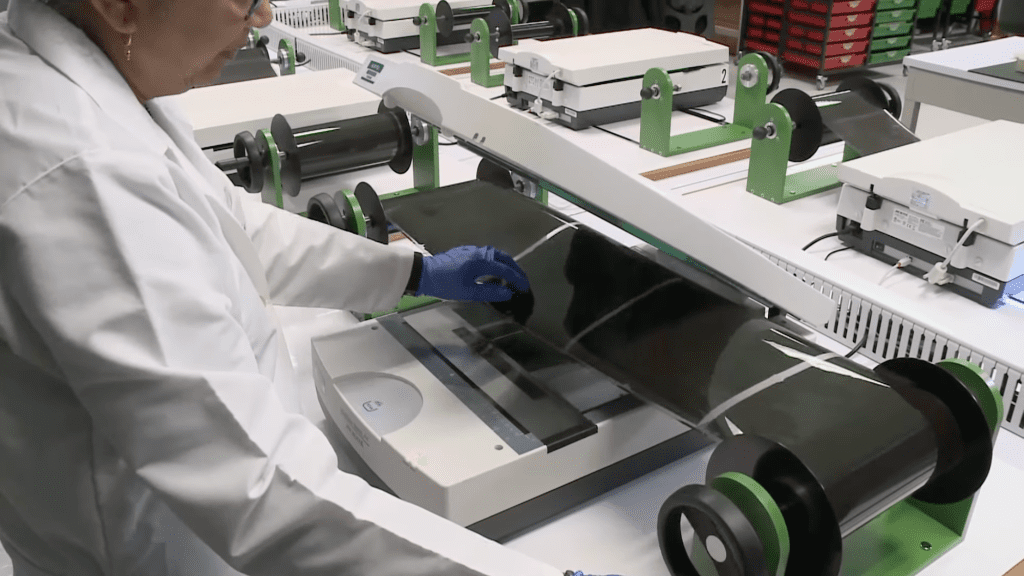

To achieve the task, workers will use the National Archives’ recently renovated, 18,000-square-foot digitization center in College Park, Maryland. The facility has new high-speed scanners and overhead camera systems that can process records up to 10 times faster than before. Without them, the National Archives almost certainly couldn’t meet their current goal of converting and making 500 million pages of records accessible by September 2026.

A ‘bionic eye’ scan of an ancient, scorched scroll points to Plato’s long-lost gravesite.]

This month, archivists will reportedly start with naturalization petitions from US immigrants who served in the military between 1918 and 1947. According to CIO Pamela Wright, these documents can provide various details about an individual’s military service.

The resulting information will also help fill in the gaps left by a major fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis in 1973. Over 15 million military files—including 80 percent of information on soldiers discharged between 1912 and 1960—were lost during the blaze.