U.S. immigration courts are moving towards procedures that are more suitable for children, but whether these procedures will effectively protect minors in immigration proceedings depends on the available funding.

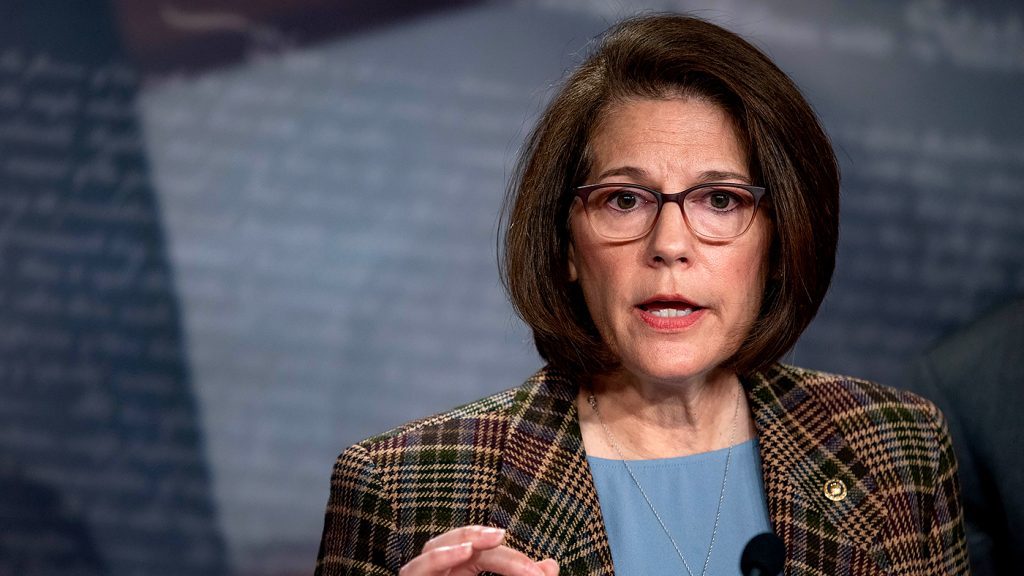

A group of 18 senators, led by Sens. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Catherine Cortez Masto (D-Nev.), are urging the upper chamber’s budget planners to carefully consider the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) procedures when developing the fiscal 2025 budget.

The 18 senators, including Sens. Patty Murray (D-Wash), Susan Collins (R-Maine), Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.), and Jerry Moran (R-Kan.), emphasized a December memorandum from EOIR Director David Neal with guidelines on how to handle cases involving minors in a letter.

They stated that if the Director’s Memorandum is properly enforced, it could help children comprehend and participate in their court proceedings by providing adjustments that suit a child’s developmental level.

It could also ease the burden on the immigration courts by grouping similar cases together and streamlining the handling of pending cases of children with claims awaiting review by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), thereby preventing duplicate efforts by multiple government agencies.

EOIR, the immigration court system, is part of the Department of Justice, functioning as an administrative court rather than part of the judiciary.

Its funding falls under the jurisdiction of the Commerce, Judiciary and Science (CJS) Appropriations Subcommittee, led by Shaheen and Moran, while Murray and Collins lead the Senate Appropriations Committee.

In their letter, the senators led by Bennet and Cortez Masto request the budget planners to include specific language in the fiscal 2025 Committee report, commending EOIR for Neal’s memorandum, and instructing the Department of Justice to submit a report detailing its implementation.

The proposed language specifies that the report should cover the name and number of immigration courts implementing juvenile dockets, training for judges handling juvenile dockets, protocols for assessing court compliance with the memorandum, methods used by courts to facilitate legal representation for children, and any resources conserved by using juvenile dockets.

Because EOIR is not part of the judiciary, standard constitutional protections offered to criminal defendants are not required in immigration cases.

This means that individuals in immigration proceedings do not have the right to an attorney, even if they do not understand the allegations against them or the consequences of their actions in court.

Neal’s memorandum instructs immigration judges to take certain steps to protect children in proceedings, including basic issues such as understanding an oath and sworn testimony.

According to part of Neal’s memo, the immigration judge should ensure that the child understands the oath at a level appropriate to their age, reassure them that they can say “I don’t know” if unsure how to answer a question, and explain that they should not feel at fault if an attorney objects to a question.

However, despite those administrative safeguards, EOIR is having difficulties in creating safe and fair environments for children who are essentially on trial.

According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, which is a government data tracker at Syracuse University, 31 percent of all foreign nationals who received a notice to appear in 2022 were 17 or younger, and 16 percent were 18 to 24 years old.

Neal’s memo states that immigration courts should have a separate docket for people under 21.

“The Memorandum also outlines certain procedures and practices that immigration judges should follow in order to create an environment where children can better understand and participate in their proceedings and where judges can better administer justice. Ideally, the immigration courts will seek to engage legal service organizations that represent unaccompanied children in the juvenile dockets with the goal of maximizing legal representation,” says the letter led by Bennet and Cortez Masto.

In November, Bennet put forward a bipartisan bill that would create a separate children’s court within EOIR, with judges and court officials specialized in handling children.