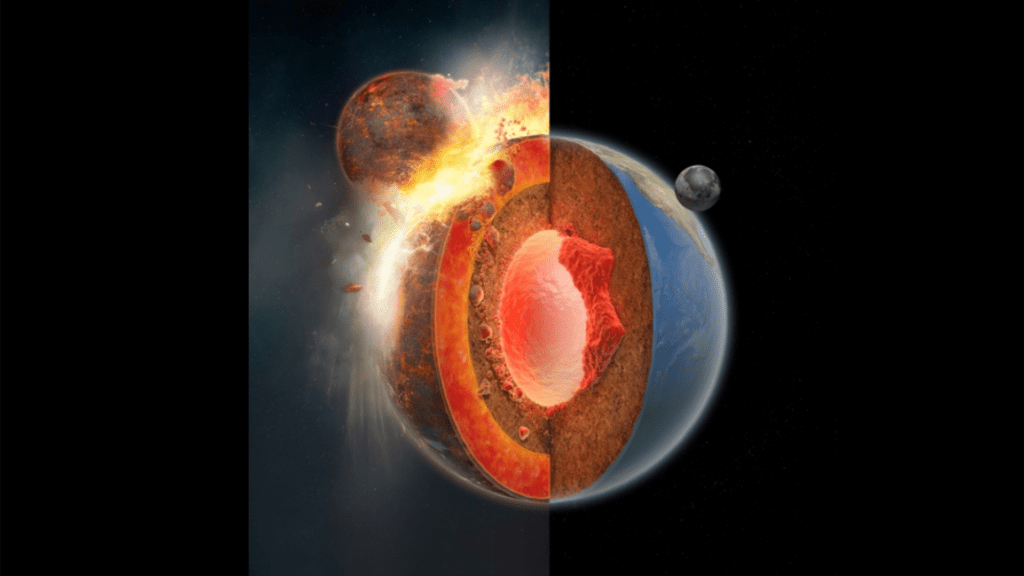

Volcanoes and earthquakes are powerful and interesting forces on Earth, but where they come from has been somewhat hard to understand. Plate tectonics are the outcome of a huge collision about 4.5 billion years ago, when an object the size of the planet Mars crashed into Earth. This event led to the formation of unusual masses within our planet, potentially leading to plate tectonics, as per new computer modeling research. This new theory is detailed in a report released on May 7 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

What are these strange masses?

In the 1980s, scientists first found two continent-sized masses of an uncommon material deep near the center of the Earth. One mass is located below the Pacific Ocean and the other is under the African continent. Both are twice the size of our moon. They are so big that if they were placed on Earth’s surface, they would cover an area about 60 miles thick around the planet.

Officially known as large low-velocity provinces (LLVPs), they are also likely made of different proportions of elements than the mantle that surrounds them. A 2023 paper published in the journal Nature suggested that they are the remnants of an ancient planet called Theia that collided with Earth in the same massive impact that created the moon. The study suggests that most of Theia was absorbed into our young planet, forming the LLVP masses. The remaining debris formed the moon.

Earth’s earliest continent? Likely a massive continental crust.]

“The moon appears to have materials within it representative of both the pre-impact Earth and Theia, but it was thought that any remnants of Theia in the Earth would have been ‘erased’ and homogenized by billions of years of dynamics (e.g., mantle convection) within the Earth,” Arizona State University astrophysicist and co-author of the Nature report Steven Desch said in a statement. “This is the first study to make the case that distinct ‘pieces’ of Theia still reside within the Earth, at its core-mantle boundary.”

The study suggests that these masses themselves then led to the formation of our planet’s plate tectonics, which enabled life to thrive.

A new examination of some very old minerals

This new paper expands on that study. Using computer modeling, they concluded that around 200 million years after the impact with Theia, the submerged LLVP masses may have helped create the hot plumes inside Earth that disrupted the surface. They breached the flat crust and allowed circular slabs to sink down in a process called subduction.

According to the team, it may explain why the Earth’s oldest minerals are zircon crystals that seem to have undergone subduction over 4 billion years ago and may have contributed to plate tectonics.

How old is Earth? It’s a surprisingly tough question to answer.]

“The giant impact is not only the reason for our moon, if that’s the case, it also set the initial conditions of our Earth,” California Institute of Technology geoscientists and study co-author Qian Yuan told The Washington Post.

The model raised numerous questions for some outside geologists, including whether or not the collision would have resulted in a recycling of Earth’s entire crust instead of plate tectonics. This process possibly happened on our planet Venus billions of years ago. Some scientists also have doubts about the theory of planet collision, citing inconsistencies in the planet's geochemistry as a whole.

Do life really need plate movements?

While they can cause damage to both property and lives, some scientists think that plate movements help Earth maintain the carbon cycle. This process transfers carbon among microbes, plants, minerals, animals, and Earth’s atmosphere. Carbon, the fourth most common element in the universe, can also create the complex molecules on Earth such as DNA and proteins. These carbon building blocks make life on Earth possible.

However, another study released last year in Nature suggests that mobile plate movements were not occurring on Earth around 3.9 billion years ago when the first signs of life appeared on Earth.

Your ancestors may have originated from Mars.]

“We found there wasn’t plate tectonics when life is first thought to originate and that there wasn’t plate tectonics for hundreds of millions of years after,” University of Rochester paleogeologist John Tarduno stated. “Our data indicates that when we’re searching for exoplanets that support life, the planets do not necessarily have to have plate tectonics.”

What is certain is that definitive answers to the question of how, when, and why life first appeared on our planet and what role the shifting plates played or did not play will persist.