Venus is our closest planet and is often called Earth's twin because it's similar in size. However, it is very different when it comes to water. Venus is extremely dry, with only a small amount of water vapor in its atmosphere, unlike Earth which is mostly covered by oceans.

In a research paper released recently, Nature, scientists from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at Colorado University, Boulder (CU Boulder), have suggested that HCO+ dissociative recombination is the main process currently taking away Venus's hydrogen and, as a result, its water. This discovery goes against some previous ideas and provides new understanding of Venus's harsh environmental conditions.

A very dry planet

“Water is really important for life,” said Eryn Cangi, LASP research scientist and co-lead author of the paper. “We need to understand the conditions that support liquid water in the universe, and that may have produced the very dry state of Venus today.”

Venus is very dry. If you distributed all the water from Earth on the second planet from the Sun, it would make a two-mile (three-kilometer) deep layer. In contrast, on Venus, where all the water is in the atmosphere, you would end up with only 1.2 inches (three centimeters), which is not enough to soak your toes.

“Venus has 100,000 times less water than the Earth, even though it’s basically the same size and mass,” said Michael Chaffin, co-lead author of the study and a research scientist at LASP.

Earth’s sister planet wasn’t always so dry. Scientists suspect that during the formation of Venus billions of years ago, the planet received about the same amount of water as Earth. However, something went wrong. Clouds of carbon dioxide in Venus’ atmosphere triggered an intense greenhouse effect, resulting in surface temperatures reaching a scorching 900 degrees Fahrenheit (482 Celsius). As a result, all of Venus’ water turned into steam and most of it drifted away into space. However, for some, the ancient evaporation theory doesn’t fully explain Venus’s current dryness or its ongoing water loss into space.

“For instance, if I poured out the water in my water bottle, there would still be a few drops left,” Chaffin said.

A major part of this puzzle

On Venus, however, almost all of those remaining drops also vanished.

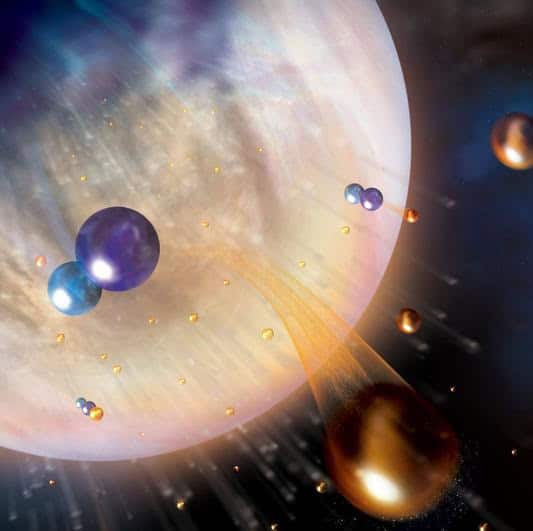

The CU Boulder team used advanced computer simulations to study different chemical reactions on Venus. They found that HCO

dissociative recombination was largely ignored in previous research but is now considered crucial in explaining Venus's current dry state.+ dissociative recombination occurs when HCO

HCO+ ions (reactive molecules made of hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen) in the upper atmosphere of Venus interact with electrons and break apart. This releases hydrogen atoms with enough speed to escape Venus' gravitational force.+ “One of the surprising conclusions of this work is that HCO

should actually be among the most abundant ions in the Venus atmosphere,” Chaffin said.+ This study not only gives us a better understanding of the Venus atmosphere, but also has wider implications for understanding water loss in other planets.

Although these findings are important, measuring HCO

directly in Venus’s atmosphere has been impossible due to limitations in previous missions. The team highlights the importance of future spacecraft with the right tools to detect HCO+ ions directly. Future missions like NASA’s Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (+ ) mission are ready to explore the mysteries of Venus’ atmosphere, although they won’t have the ability to detect HCODAVINCIWhile DAVINCI cannot detect HCO+.

, researchers are hopeful that a future mission may reveal more about water on Venus.+“There haven’t been many missions to Venus,” Cangi said. “But newly planned missions will use decades of experience and a growing interest in Venus to explore the extremes of planetary atmospheres, evolution and habitability.”

Some people don't believe previous theories anymore.