A wild animal from Indonesia named an orangutan was seen making a medicinal paste and putting it on a wound on its face to help it heal faster. The treatment worked well and suggests the animal has advanced abilities to treat itself with medicine.

This impressive behavior shows a clear example of actively treating a wound with a type of plant that is known to have biologically active substances, as noted by the researchers who recorded the event.

Self-medicating orangutan

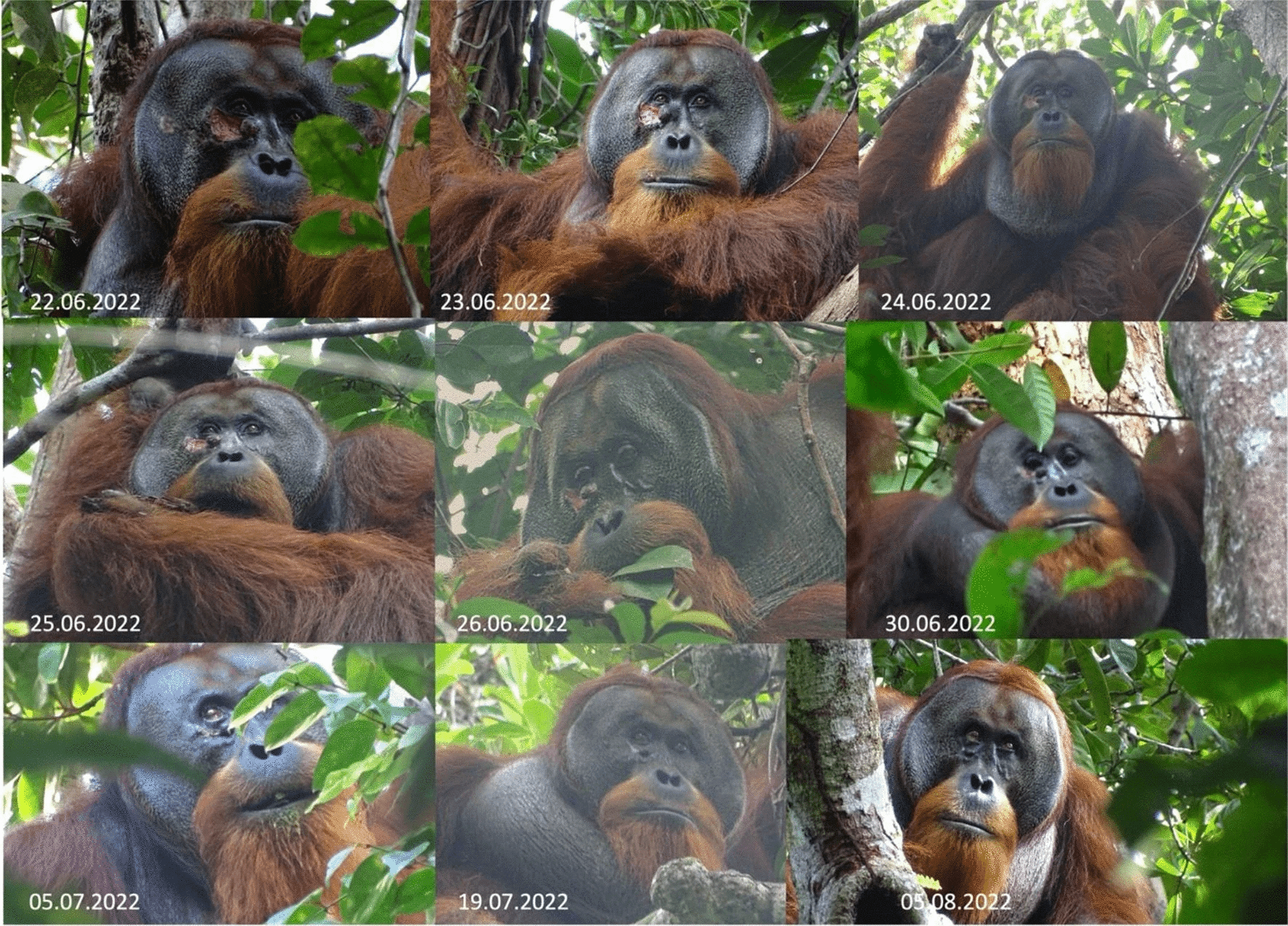

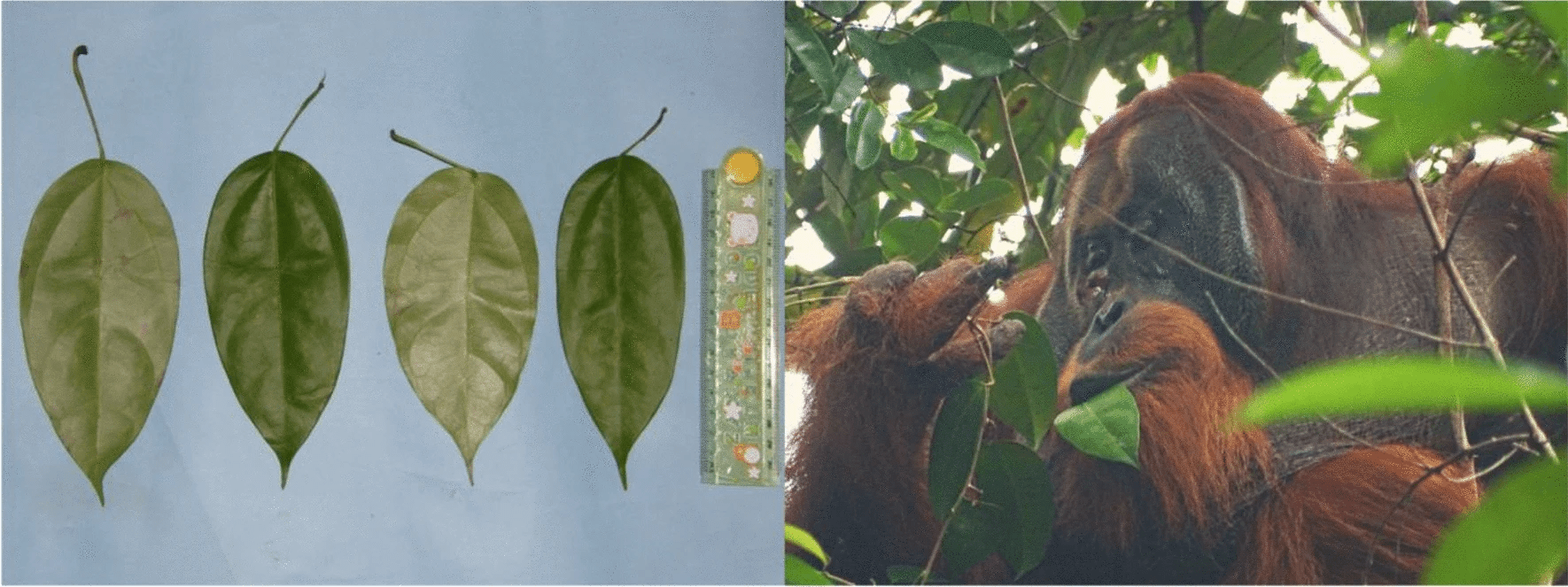

The whole thing began at the Suaq Balimbing research site in Indonesia. An orangutan named Rakus got into a bad fight with another male. The fight left him with a bad wound on his face. Three days after the injury, Rakus started picking and tearing the leaves of a woody vine called Fibraurea tinctoria.

The vine is known for its pain-relieving effects. It is also sometimes used to reduce fever and as a diuretic. It also contains some anti-inflammatory and antibacterial compounds. Rakus collected the leaves and started chewing them. Rakus applied the resulting juice onto his face and finally covered his wound completely with chewed leaves.

There’s no reason to believe this is anything other than self-medication, according to researchers.

“Rakus’s behavior seemed to be deliberate as it selectively treated the wound on his right cheek pad with the plant juice and not other body parts. The behavior was also repeated several times, not only with the plant juice but also later with more solid plant material until the wound was completely covered. The whole process took a significant amount of time,” said lead author Isabelle Laumer.

“This study may present the first report of actively managing a wound with a biologically active substance in a great ape species and offers new insights into the existence of self-medication in our closest relatives and in the evolutionary origins of wound treatment in general,” the study also states.

The treatment was successful. Only five days later, the wound had closed and there was no infection. Additionally, Rakus was also aware that it needed to rest more.

“Interestingly, Rakus also rested more than usual when injured. Sleep has a positive effect on wound healing as the release of growth hormone, protein synthesis, and cell division are increased during sleep,” Laumer explained.

Just like humans used to do

This behavior once again suggests that evolutionarily, orangutans are not that far behind humans. This is the first time we’ve noticed this behavior, but orangutans may have been self-medicating for a long time.

Scientists say that this behavior is so similar to humans that it might have developed in our shared ancestor with orangutans.

Caroline Schuppli, senior author of the study, says that the first mention of treating human wounds was likely in a medical manuscript from 2200 BC, which included cleaning, plastering, and bandaging wounds with specific substances for wound care.

The recognition and use of substances with medical or functional properties on wounds may have a common underlying mechanism for both African and Asian great apes, indicating that our last common ancestor may have displayed similar ointment behavior.

Orangutans are not the only primates to do this. In the 1960s, Jane Goodall observed chimps with whole leaves in their feces, later confirmed to have therapeutic and anti-parasitic benefits.

Since then, various forms of self-medication have been observed in nature.

Animals also self-medicate

Researchers typically categorize self-medication into:

- Sick Behaviors: Displaying symptoms of illness such as anorexia.

- Avoidance Behaviors: Avoiding feces, contaminated food, or water.

- Prophylactic Behaviors: Regular consumption of foods known for their preventive health benefits.

- Therapeutic Behaviors: Ingesting small amounts of biologically active or toxic substances with minimal nutritional value to treat diseases or symptoms.

- Therapeutic Topical Application: Topically applying pharmacologically active plants to treat external health conditions or using such plants in nests as fumigants or insect repellents.

The latter is perhaps the most complex, and several animals have been observed doing it.

North American brown bears (Ursos arctos) make a paste of Osha roots (Ligusticum porteri) and saliva. They then rub their fur in this paste to repel insect bites and soothe existing bites. Navajo Indians are said to have learned to use this root medicinally from the bear. Bees also use resins as medication after a fungal infection and a chimpanzee in Gabon was spotted treating a wound with insects that contain medicinal compounds.

Rakus has now entered a very select group of creatures, but an important question remains: how did this behavior emerge? Is it that Rakus experimented with different plants and innovated it himself, or did he learn it from somewhere else?

“It is possible, that wound treatment with Fibraurea tinctoria by the orangutans at Suaq emerges through individual innovation,” says Schuppli. “Orangutans at the site rarely eat the plant. However, individuals may accidentally touch their wounds while feeding on this plant and thus unintentionally apply the plant’s juice to their wounds. As Fibraurea tinctoria has potent analgesic effects, individuals may feel an immediate pain release, causing them to repeat the behavior several times.”

In any case, this suggests that self-medication in nature may be much more widespread and common than previously thought. In the coming years, it is likely that more human-like treatments will be discovered through close observation of our primate relatives, according to Laumer.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.