A new study has discovered that a single hurricane hitting the forests in New England can reverse many years of carbon storage.

The study published on Wednesday in Global Change Biology revealed that as the oceans warm and hurricanes become more intense due to climate change, they are causing greater damage to the woodlands in the region. can knock down as many as 10 percent of standing trees in the heavily forested region.

The researchers found that even small increases in wind speed led to significant increases in damage. An 8 percent increase resulted in more than 10 times the number of severely damaged areas, while a 16 percent increase caused more than 25 times the damage.

This poses a threat to forest carbon markets, which aim to sell carbon credits earned by storing carbon from the atmosphere in the trees' growing bodies.

With many businesses turning to carbon credits to offset their greenhouse gas emissions, the forest carbon market, expected to reach $100 billion by the end of the decade and a quarter trillion by midcentury, is likely to expand. This information comes from Morgan Stanley. about 15 percentof the nation’s fossil fuel emissions, according to the Department of Agriculture. The agency and state partners have sought to encourage markets in which landowners can sell the carbon stored in their growing forests on regional and international markets.

There is much debate surrounding whether carbon offsets actually reduce emissions. However, all carbon offset schemes rely on the idea that carbon is being permanently removed from the atmosphere, which depends on the trees remaining standing. Shersingh Joseph Tumber-Dávila, a coauthor of the study from Dartmouth College and Harvard Forest, emphasized the importance of adequately addressing the risks to forest carbon if it is going to be a primary tool to combat climate change, as current policies and voluntary/compulsory carbon markets seem to suggest. of Tumber-Dávila's work suggests that companies involved in forest carbon storage face the risk of insolvency, akin to a bank without enough capital reserves to handle a sudden surge in deposits. He also stated that current carbon market policies are not adequately prepared for these risks, as a single hurricane has the potential to release the equivalent of 10-plus years' worth of carbon sequestration from New England forests.

In California's regulated carbon market, which is the largest in the U.S., less than 3% of carbon credits are reserved to mitigate catastrophic risks, highlighting the impact of events like hurricanes or wildfires on carbon offsets.

The loss of trees due to storms or fires can obliterate those carbon offsets. This has posed a significant problem for companies in the West Coast, such as Green Diamond, which received substantial funds from tech companies to offset their fossil fuel usage with forest protection, only to face devastating wildfires driven by climate change.

tear apart their forests

, as per Oregon Public Broadcasting.

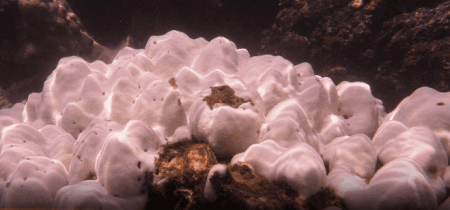

The broadcaster reported that the project relied on live trees. Over time, they would gather carbon dioxide and, using photosynthesis with sunlight and water, store more of it in their wood.

However, in a single fire, the company lost live trees that held down 3.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — equivalent to the yearly emissions from 700,000 cars' tailpipes. The Global Change Biology study broadens this research from just wildfires to include the damage caused by storms.Unlike fires, the damage caused by storms is not immediate: fallen trees can take up to two decades to become a net source of emissions and up to a century to fully decompose, countering the carbon stored by the regrowing forest.

Nevertheless, the authors expressed concern about the future of New England's forests on a warming planet, as well as their value as a financial asset for companies trying to reduce emissions.

One storm is likely to use up what's set aside for risks over 100 years, Tumber-Dávila pointed out.

A single hurricane hitting New England forests can reverse decades of carbon storage, as indicated by a new study. As climate change warms oceans and energizes hurricanes, more severe storms with faster winds are delving deeper into the region's woodlands, according to the findings published on Wednesday in Global Change Biology. Now, a single large storm can demolish…

Unlike that done by fires, however, this damage isn’t instantaneous: fallen trees take up to two decades to become a net source of emissions — countering the carbon stored by the forest regrowing around them — and up to a century to fully break down.

Nonetheless, the writers expressed caution about the future of New England’s forests on a heating planet — not to mention their utility as a financial instrument for companies unable to cut emissions.

A single storm, Tumber-Dávila noted, “is likely to deplete what is set aside for risks over 100 years.”