Letters penned by the well-known British mountain climber and explorer George Mallory Mount Everest explorer George Mallory's correspondence has been digitized and can now be accessed by the public for the first time. The University of Cambridge’s Magdalene College has digitized its collection of the mountaineer’s correspondence. The letters are available for download here ahead of the upcoming 100th anniversary of Mallory’s final attempt to climb Mount Everest.

Mallory is famous for responding with “because it’s there” when asked why he wanted to risk death and climb Mount Everest. He took part in a reconnaissance expedition to produce the first European maps of the mountain in 1921. His first serious attempt at climbing the mountain was in 1922, with two subsequent attempts at climbing the mountain following. Most of the correspondence is between Mallory and his wife Ruth and was housed at his alma mater Magdalene College following his death on Mount Everest in 1924.

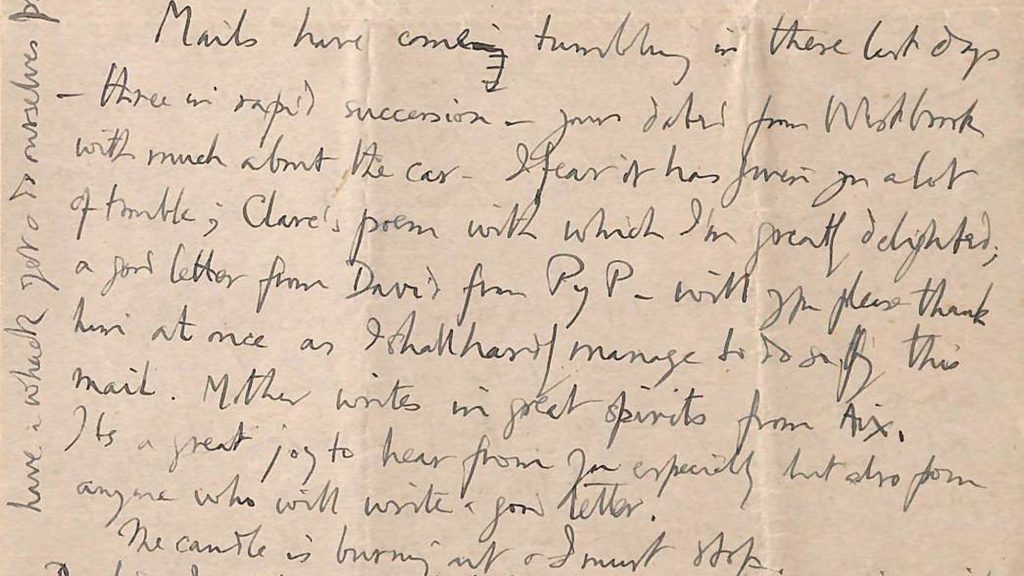

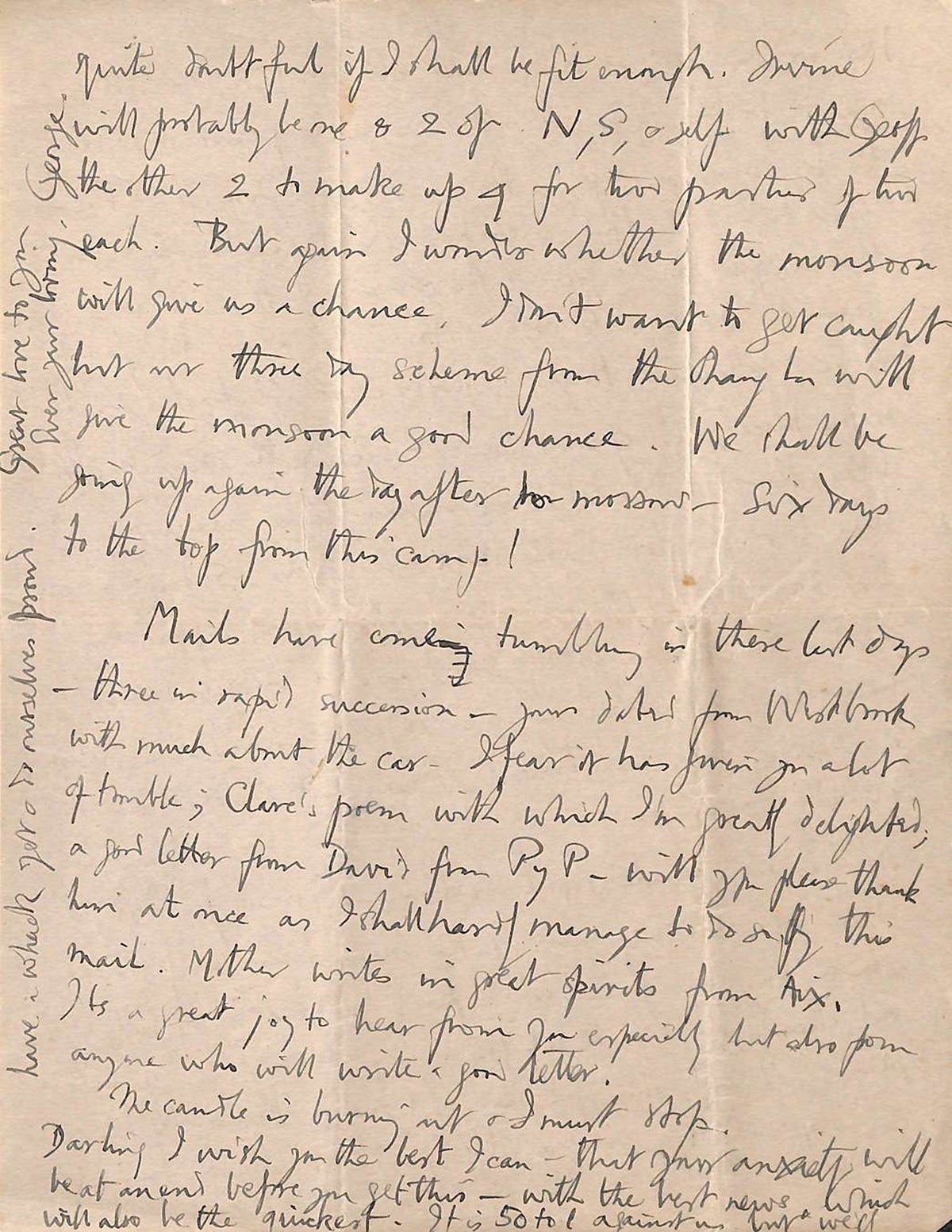

In his final letter to his wife Ruth before his doomed last attempt to climb the mountain, George wrote: “Darling I wish you the best I can–that your anxiety will be at an end before you get this–with the best news. Which will also be the quickest. It is 50 to 1 against us but we’ll have a whack yet & do ourselves proud. Great love to you. Ever your loving, George.”

Who was George Mallory?

George Mallory (1886-1924) was one of the leading members of the early European teams to explore Mount Everest. At 29,032 feet, Mount Everest is the highest mountain in the world. It rises from the Great Himalayas of southern Asia on the border of Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. It was previously referred to as Peak XV and was renamed for British explorer Sir George Everest in 1865.

The increase in Everest deaths may have nothing to do with crowds or waiting.]

In May 1924, Raymond J. Brown from Popular Science magazine chronicled Mallory’s upcoming expedition which would be his last. Brown wondered, “Nature controls the situation through the physical capacities with which she has invested in man. Can a man at a height of 27,000 feet develop the energy to walk or drag himself higher?”

On June 6, 1924, Mallory and a newer climber named Andrew Irvine began an attempt to reach the summit. The last time the pair was spotted alive was June 8, and the debate as to whether or not Mallory reached the summit continues to this day, as he could have reached the summit and died on the way down.

During the 1930’s, Irvine’s ax was discovered at roughly 27,700 feet. In 1975, a Chinese climber named Wang Hongbao found a body. He said that the body was an old “English dead” due to the vintage clothes. At the time, no other English climber was known to have died at that elevation on the mountain, so it was presumed that the body could be George Mallory or Andrew Irvine. In addition, an oxygen canister from the 1920s was later unearthed in 1991.

Using these clues, a group of people went on a journey in 1999 to look for Mallory and Irvine. They found Mallory’s body at 26,760 feet and believe that he died after a bad fall. Irvine’s remains have never been found. expedition set out in 1999 to search for both Mallory and Irvine. The team found Mallory’s body at 26,760 feet and it’s believed that he died after a bad fall. Irvine’s remains have never been found.

What is in this collection of letters?

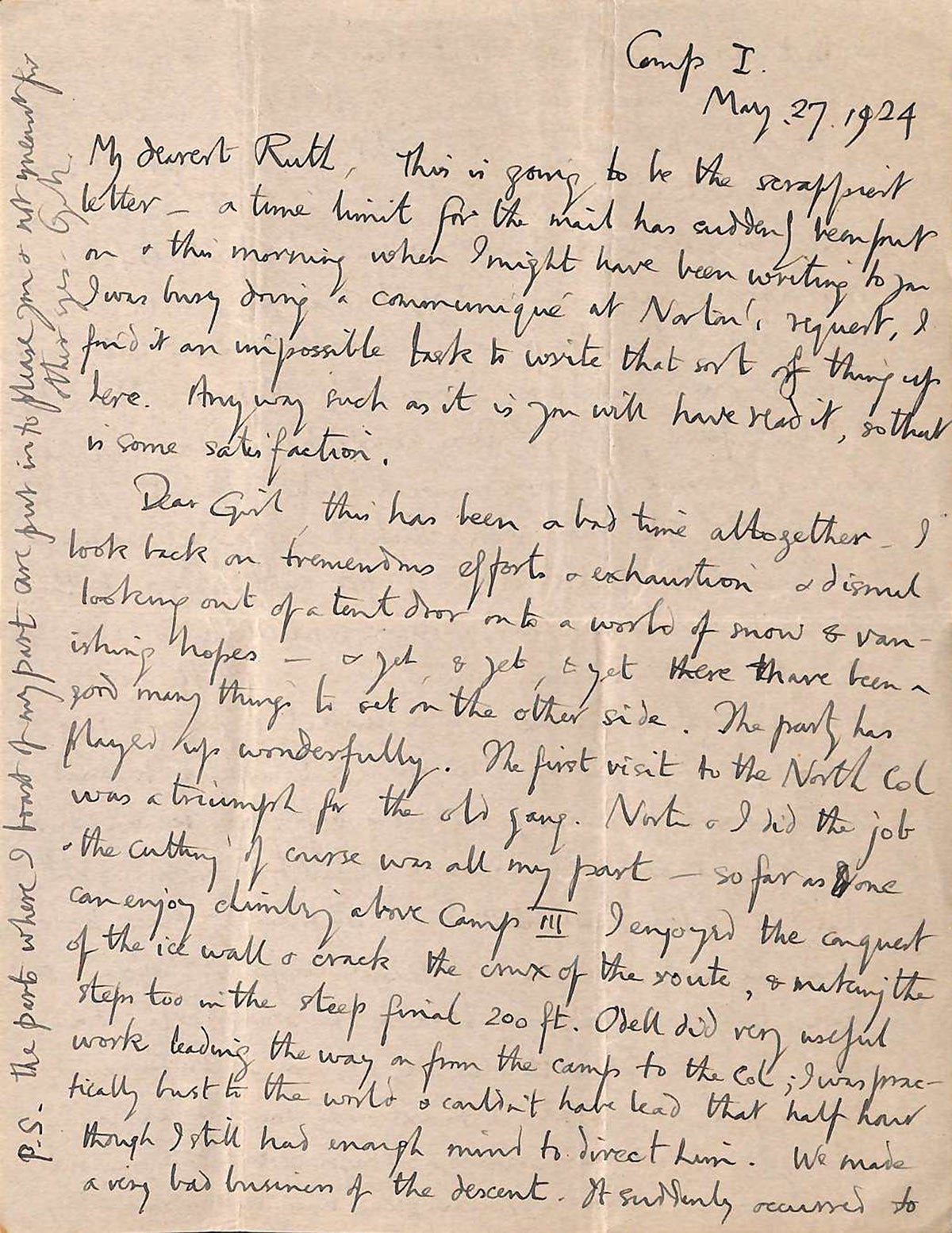

The majority of the letters in this collection are correspondence between Mallory and his wife Ruth from the time of their engagement in 1914 until his death. The last letter that he wrote and sent in May 1924 before his final Everest attempt is in the collection.

Also, three letters that were recovered from his body in 1999 are included in this new collection. The letters survived 75 years in his jacket pocket before his body was discovered and are included in the collection with his other letters.

The collection covers various topics including his first mission to Everest in 1921 to see if it was even possible to get to the base of the mountain. It also includes an account of his second mission that ended in disaster when eight Sherpas were swept off the mountain and killed in an avalanche. In the letters, Mallory often blamed himself for the tragedy.

Mallory also details his service in World War I in the letters, including a detailed account of the deadly Battle of the Somme in 1916. Mallory’s letters even detail a visit to the United States during Prohibition in 1922. He describes visiting speakeasies, asking to be served milk, and getting whiskey through a secret hatch.

The rocky history of a missing 26,000-foot Himalayan peak.]

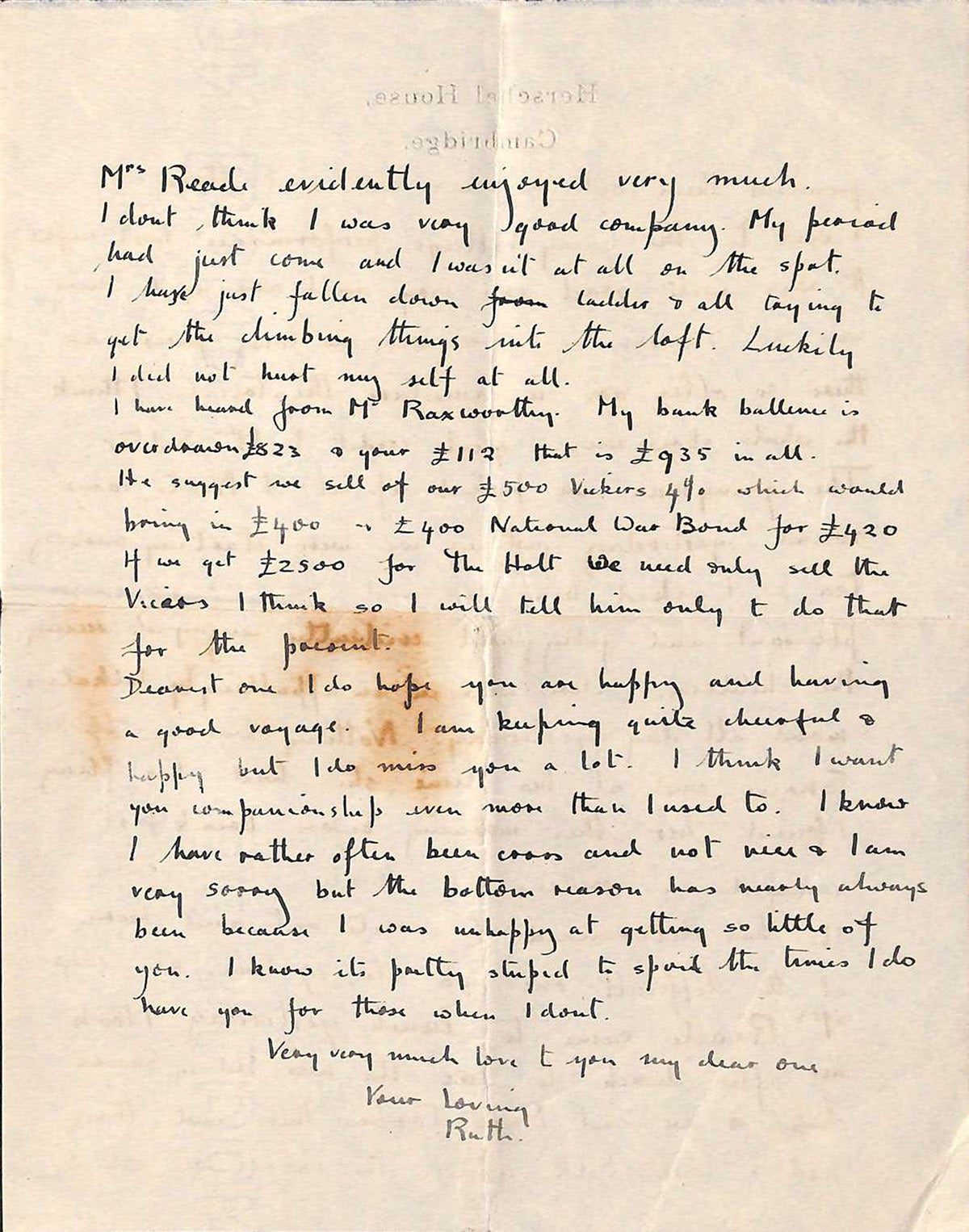

According to the team from Magdalene College, the letters from his wife Ruth are a major source of women’s social history, as they detail a wide variety of topics about her life as a woman living through World War I.

In the only surviving letter from the Everest period in the archive, Ruth wrote: “I am keeping quite cheerful and happy but I do miss you a lot. I think I want your companionship even more than I used to. I know I have rather often been cross and not nice and I am very sorry but the bottom reason has nearly always been because I was unhappy at getting so little of you. I know it is pretty stupid to spoil the times I do have you for those when I don’t.”

“It has been a real pleasure to work with these letters,” archivist Katy Green said in a statement. “Whether it’s George’s wife Ruth writing about how she was posting him plum cakes and a grapefruit to the trenches (he said the grapefruit wasn’t ripe enough), or whether it’s his poignant last letter where he says the chances of scaling Everest are ‘50 to1 against us,’ they offer a fascinating insight into the life of this famous Magdalene alumnus.”