We typically think of evolution as a tree, with separate animal kinds as leaves on an evolutionary branch. Sometimes, though, the leaves mix together. Two different animal kinds can sometimes make babies called hybrids. The most common example is the mule, the baby of a horse and a donkey.

Animal hybrids are often unable to have babies, especially when there are significant genetic differences between the parent kinds. However, there are exceptions. Sometimes, the hybrids can have babies, especially if the parent kinds are genetically similar. In the new study, researchers describe a remarkable example. Not only were these butterfly hybrids able to have babies — they made a new kind of animal.

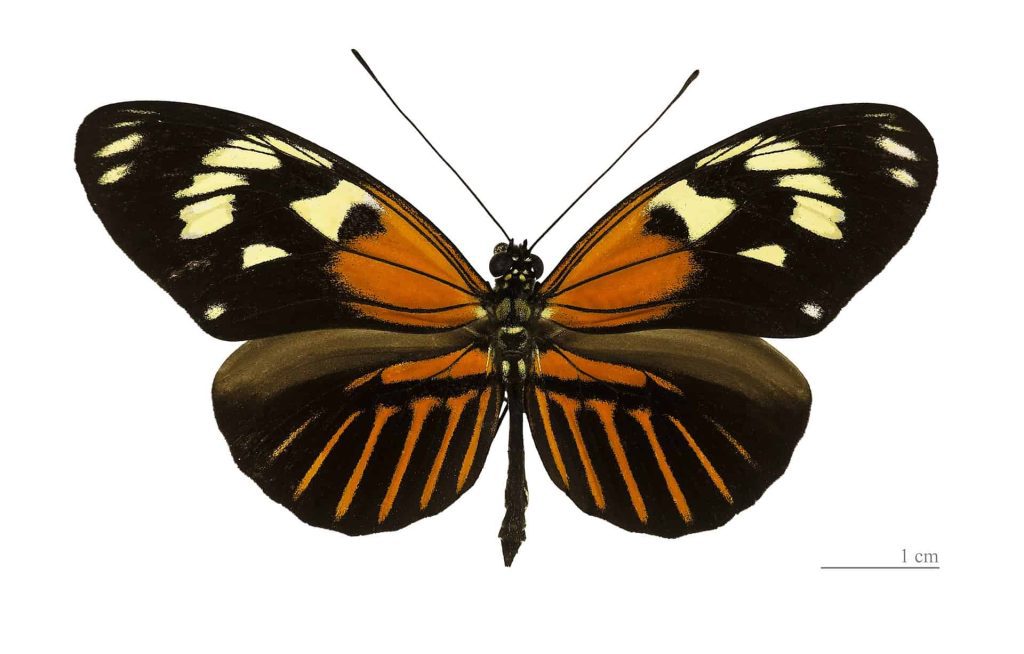

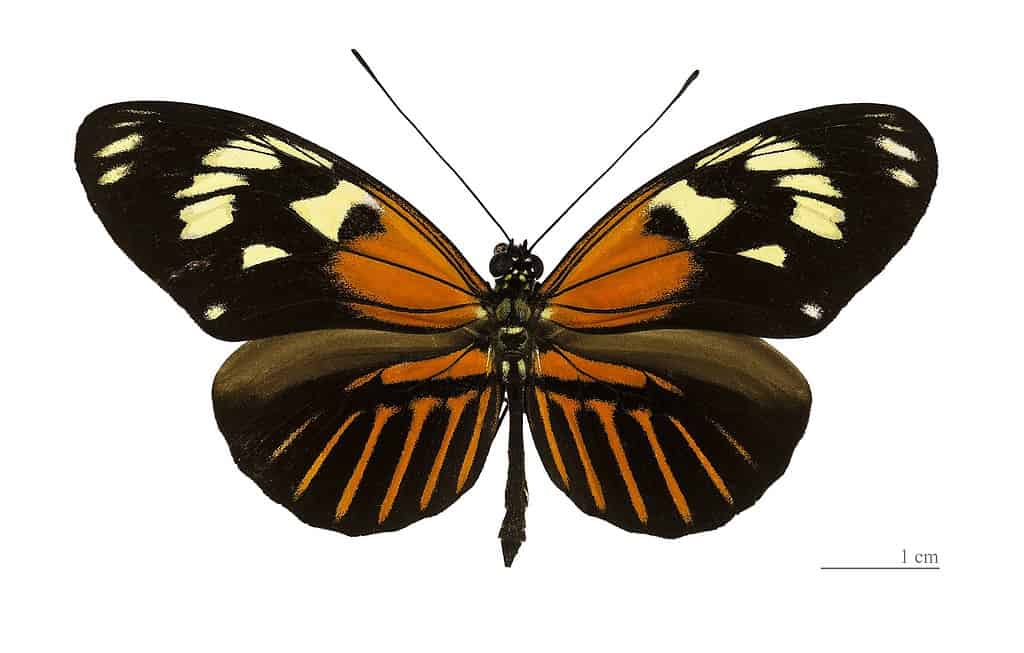

Heliconius butterflies are incredible creatures. They’re brightly colored and their colors show that they taste bad to possible enemies, Biologists use them models for studying how, through their complex mimicry patterns, new kinds of animals encourage genetic exchange and ecological adaptation.

But hybrid kinds of animals were not expected for Heliconius.

In plants, hybrid speciation is well-documented, largely due to the doubling of chromosomes. However, in animals, such events are rare and complex, especially when the chromosome number remains unchanged. Heliconius butterflies, with their recently uncovered speciation story, provide a compelling narrative on how hybridization can drive speciation in animals.

“Historically hybridization was thought of as a bad thing that was not particularly important when it came to evolution,” said Neil Rosser, an associate of entomology at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology who co-authored the study and handled its genetic mapping with Harvard postdoctoral fellow Fernando Seixas. “But what genomic data have shown is that actually hybridization among species is widespread.”

The findings may change how we see the concept of a kind of animal. “Many kinds of animals are not intact units,” said Rosser. “They’re quite leaky, and they’re exchanging genetic material.”

Hybrid + hybrid = new kind of animal

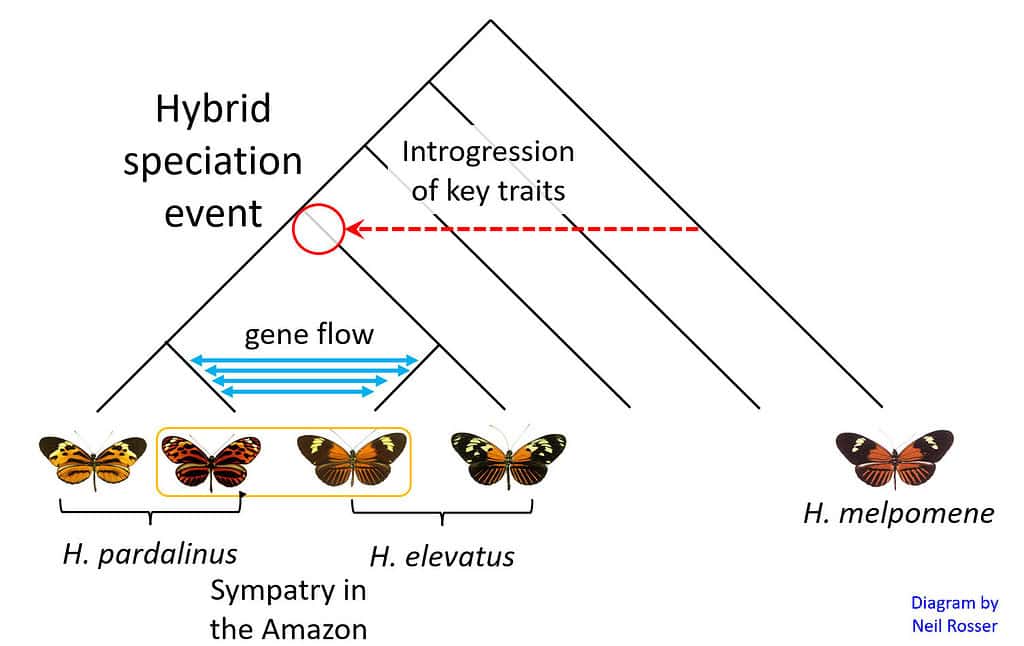

Rosser and colleagues sequenced the genome of the kind of animal Heliconius elevatus. They found that this kind of animal appeared after a hybridization event some 180,000 years ago between two other kinds: H. melpomene and H. pardalinus.

Everything about H. elevatus suggests it’s a new kind of animal. It has a distinct caterpillar host plant, different pheromones, different color patterns, wing shape, and flight — it’s an entirely new kind of animal. Even more strikingly, all three kinds of animals now live across a vast area of the Amazon rainforest, covering different ecological niches.

“Normally, kinds of animals are thought to be unable to have babies,” added co-author James Mallet, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard. “They can’t make babies that are reproductively able.” While there is now evidence of hybridization between kinds of animals, what was difficult to confirm was that this hybridization is, in some way, involved in speciation. As Mallet put it: “The question is: How can you merge two kinds of animals together and get a third kind of animal out of that merge?”

However, the vast majority of H. elevatus’ genome comes from one of the parent kinds (H. pardalinus). This small but significant genetic contribution shows an interesting aspect of evolution: sometimes, a small part of the genome can have a big impact on an animal’s evolutionary path. It’s in these genetic “islands” that we find traits that enable H. elevatus to do well in its specific area, making itself different from its original species even though genes continue to move between them.

For example, one of the most remarkable characteristics of Heliconius elevatus is its wing coloring. These colors are not just for show; they have an important role in mimicry, which helps protect the butterflies from predators. In Heliconius , mimicry is a well-studied occurrence. Different species have similar wing patterns to signal their toxicity, a survival tactic that reduces the chance of being eaten.

Species can pass on genes

The new research is more than just discovering a rare event: the situation with Heliconius elevatus challenges the traditional ideas about the development of new species and their adjustment. This might even change our understanding of what a species is.

It demonstrates that species may not be as clearly defined as previously believed — the branches on the evolutionary tree are not always distinct. Previous studies have already indicated that the distinction between species and subspecies is not as evident as once assumed, and in the last decade or two, researchers have found more evidence that hybridization also plays a role in this process.

“In the last 10 or 15 years, there has been a change in the way we view the importance of hybridization and evolution,” Rosser said. Previously, it was thought that hybridization hindered the development of new species. Now, it seems to be the opposite. “The species that are evolving are constantly exchanging genes, and as a result, this can actually lead to the development of entirely new lineages,” Rosser explained.

The study was released in Nature.