Stephanie Breijo | (TNS) Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES — José Andrés spends a lot of time thinking about how food brings people together, both in and out of the most dangerous conflict and disaster zones in the world.

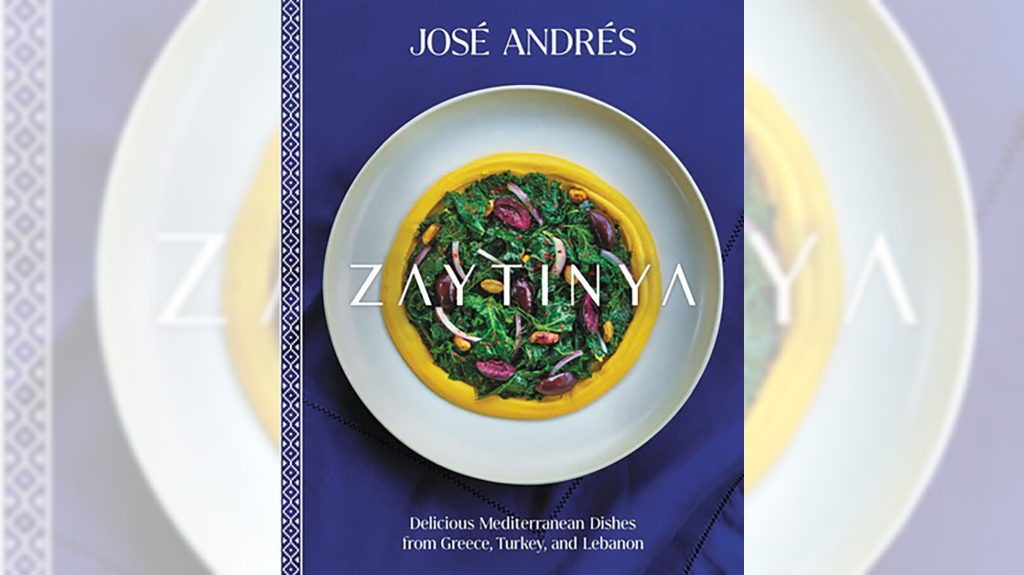

Days before an Israeli airstrike killed seven members of his aid organization working to feed Palestinians in Gaza, Andrés spoke to The Times about his recently published cookbook “Zaytinya.” Andrés is scheduled to speak at the 2024 Los Angeles Festival of Books, on April 21. The April 1 Gaza bombing that killed his fellow aid workers thrust Andrés further into the global limelight, and spurred international calls for accountability from the Israel Defense Forces and for an independent investigation.

In addition to owning dozens of restaurants spread around the globe, the Spanish chef has become synonymous with food aid through his organization World Central Kitchen, which dispatches chefs and other volunteers to feed people in the wake of wars and natural disasters.

“I wish that the world was run by people that cook and feed, because this is something that brings everybody together,” Andrés said on a phone call three days before the attack.

The Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean regions have always been particularly dear to him. The sights, scents and tastes have been a guiding force for the chef, especially over the last 22 years.

At his Washington, D.C., restaurant Zaytinya, a haute but tradition-minded exploration of Lebanon, Turkey and Greece, he pursues the culinary ties found across these cultures and the birthplace of some of the world’s most ancient and influential cuisines. He hopes his new Zaytinya cookbook will further share the beauty of the region.

Andrés and his wife, Patricia, visited cobblestone alleyways and bazaars, home kitchens and high-end restaurants across the Levant, consulting chefs and merchants and other authorities to bring the restaurant to life.

He opened Zaytinya in 2002, offering a variety of dishes inspired by Lebanese, Turkish and Greek cuisine. Eventually he would expand this restaurant to Florida and New York, and soon, to Palo Alto and Las Vegas (Los Angeles is not slated to receive Zaytinya, though an outpost of the chef’s steakhouse, Bazaar Meat, is expected to open downtown this fall, near sibling restaurants San Laurel and Agua Viva).

At Zaytinya the focus is on dishes’ shared connections. And within the cookbook, items enjoyed across the regions are titled in multiple languages.

“The meaning to me of culture is not something exclusive, but something inclusive,” he said. “It’s not something that only belongs to you, but belongs to everybody. Culture to me is the perfect synonym for longer tables, for sharing. Culture is not what I know but what I’m sharing with others, and what others are sharing with me. That’s why I never understood cultural appropriation in the way of food.”

Since he opened Zaytinya, he has seen these food traditions and many others spread to all parts of the world, especially with the internet, which has made it very easy to share these cultural connections to food.

Ingredients commonly used in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, like za'atar, can now be found not only in specialty restaurants like Lebanese Taverna or Zaytinya, but also on big-box grocery store shelves across America. He welcomes the discussion about who originated certain foods, but focusing solely on this is, in a way, missing the bigger picture.

“If we remove borders, there are people,” he said. “If we have no borders, no boundaries, there are people. Everybody enjoys hummus and falafel. There are certain things that transcend borders and boundaries, and there are dishes that belong to the people.”

“You say tzatziki, I say cacık,” he added. He has experienced this within his own culture as well, eagerly engaging in the heated debate over whether Spanish coca, or flatbread, influenced Italy's pizza on an episode of the food travel show “José Andrés & Family in Spain.”

The Zaytinya cookbook was released six months after “The World Central Kitchen Cookbook,” a large and colorful collection of recipes from around the world by Andrés and other chefs, and a book that raises funds for the organization. “He said people were requesting the recipes because it’s incredible the care that people put into recipes during crises,” he said. “It’s incredible the variety of meals we’ve prepared throughout our history.”

In many ways, the cookbooks are quite different: Zaytinya, he said, is about feeding a small number of people while the World Central Kitchen’s book is about feeding a large number. However, the concepts were similar in terms of translation and global nature: With Zaytinya, the recipes were from the restaurant and its connections to the outside world, and in the World Central Kitchen cookbook, the world serves as the restaurant.

The chef mentioned that he tries to keep his restaurant business separate from his humanitarian organization, but their philosophies sometimes overlap. In March 2020, Zaytinya served as a hub for nourishment and assistance when Andrés transformed the restaurant and his others into community kitchens during the pandemic, providing affordable dishes, pay-it-forward options, and free meals for those in need.

“Water and food should be recognized and acknowledged as a basic human right,” Andrés said. “Every person on Earth, every child, should have access to food and water, regardless of the circumstances. I don't know anyone who disagrees with this statement, but we still don't make it happen. And we're leaving people hungry.”

He continued: “Clearly that's happening right now in Gaza, but it's also happening in many places around the world. We have an abundance of the Earth's goodness, yet we still can't solve hunger even in wealthy countries.”

He knows that one restaurant, one cookbook, one nonprofit cannot solve this. However, he believes he has to try, and that the collective efforts could make a difference.

They also serve another purpose: to preserve and share culture — at least as best they can.

“Eating places are important because they anchor a specific type of cooking in a local area within the city, but there is also a lot of activity happening in people's homes,” he said.

According to Andrés and Greek food writer and consultant Aglaia Kremezi, who wrote the book’s introduction, Greek, Turkish and Lebanese cuisine can be especially difficult to reproduce in a restaurant environment because of the heartfelt, simple nature of their home cooking.

André tried kolokithokeftedes, or Greek zucchini fritters, at a small restaurant near the airport in Santorini. He had gotten lost, but a sign indicating a dining establishment attached to what appeared to be a small house caught his attention. Andrés ordered the fritters and found them to be incredible; he obtained the recipe and added them to the menu at Zaytinya but, he said, has never been able to duplicate them exactly as they were in that cozy restaurant in Santorini. In his own home he has come closer, but in the restaurant they feel further from their origins.

Despite all his innovative culinary techniques at his restaurants like Minibar and the Bazaar, much of his cuisine at eateries such as Zaytinya and Jaleo remains faithful to their origins. “In my approach to those traditional cookings,” he said, “I always hold myself accountable to be as authentic as I could from the tradition.”

Those kolokithokeftedes are featured in the Zaytinya cookbook along with many other homestyle, comforting recipes from the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East — perhaps they’re most authentic, most reproducible, when prepared at home for your loved ones too.

José Andrés is

____

slated to speak at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on Sunday, April 21, at 12:30 p.m. at Bovard Auditorium. Tickets are for sale at events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks ©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at .

. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. latimes.comThe Spanish chef has become synonymous with food aid through his organization World Central Kitchen, which sends chefs and other volunteers to provide food for people following wars and natural disasters.