Archaeologists have long been interested in how ancient societies changed their bodies for beauty, status, or cultural identity. Recently, a unique form of body modification among the Vikings has been revealed. While the Vikings are known for filing and painting their teeth, researchers have now found something even more dramatic: the deliberate reshaping of skulls into an elongated, oblong form. This discovery was made by a team studying Viking skulls from Gotland in the Baltic Sea.

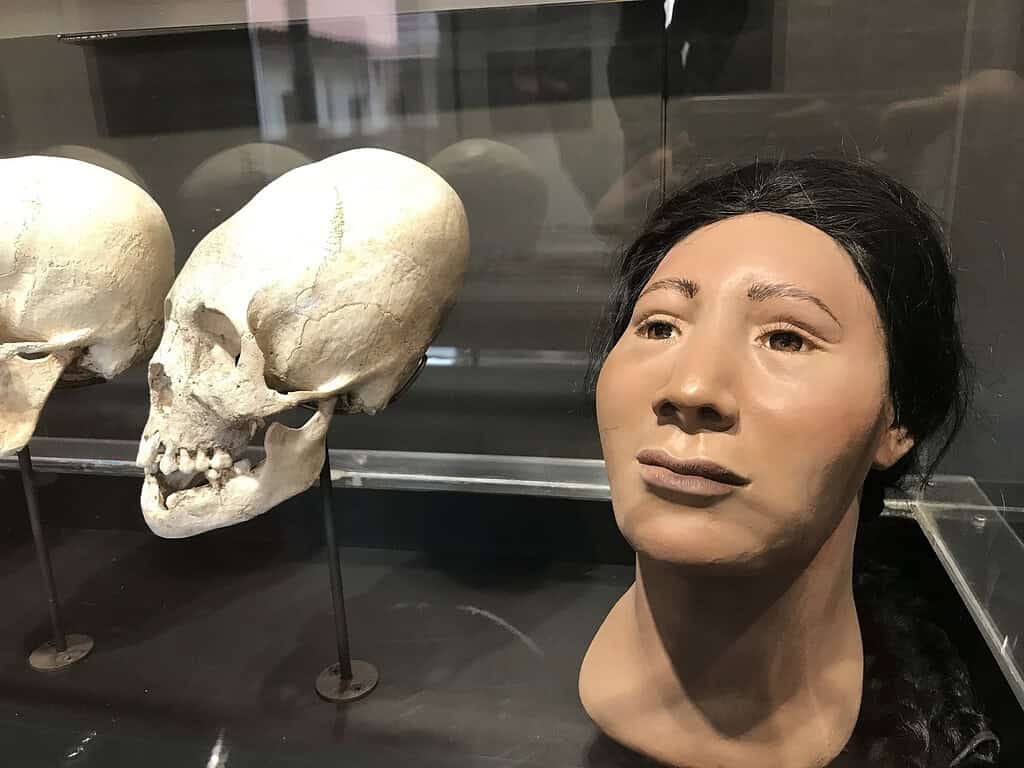

The team, led by Matthias Toplak from the Viking Museum Haithabu and Lukas Kerk of the University of Munster, identified three skulls dating back around 1,000 years and belonging to adult women. The skulls look almost alien. However, as strange as they may appear, similar skull modifications were common in other cultures. Nevertheless, this is the first time we’ve seen something like this from Vikings.

The discovery not only adds a new layer to our understanding of Viking society but also suggests an exchange of cultural practices through trade.

Uncovering Ancient Modifications

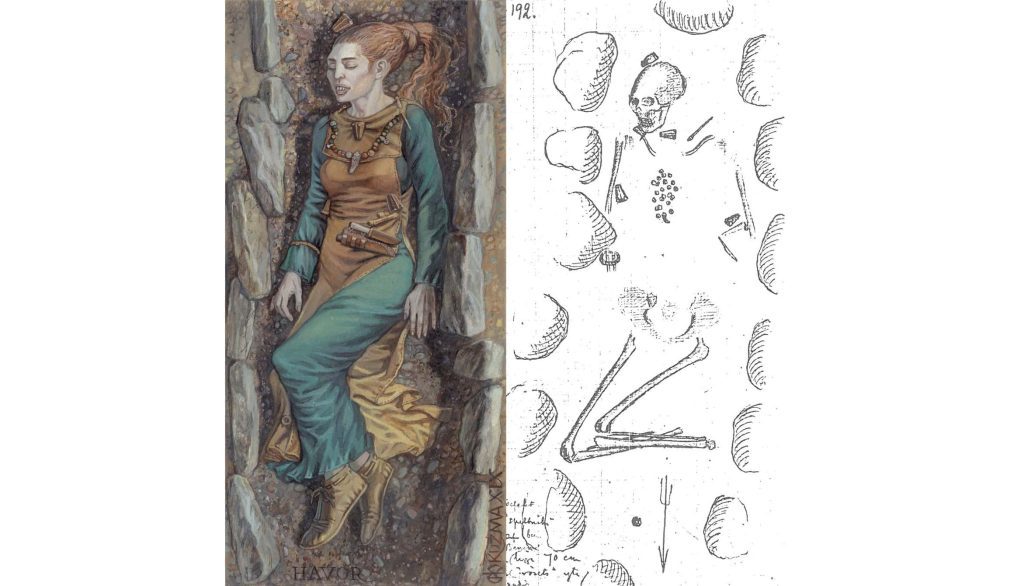

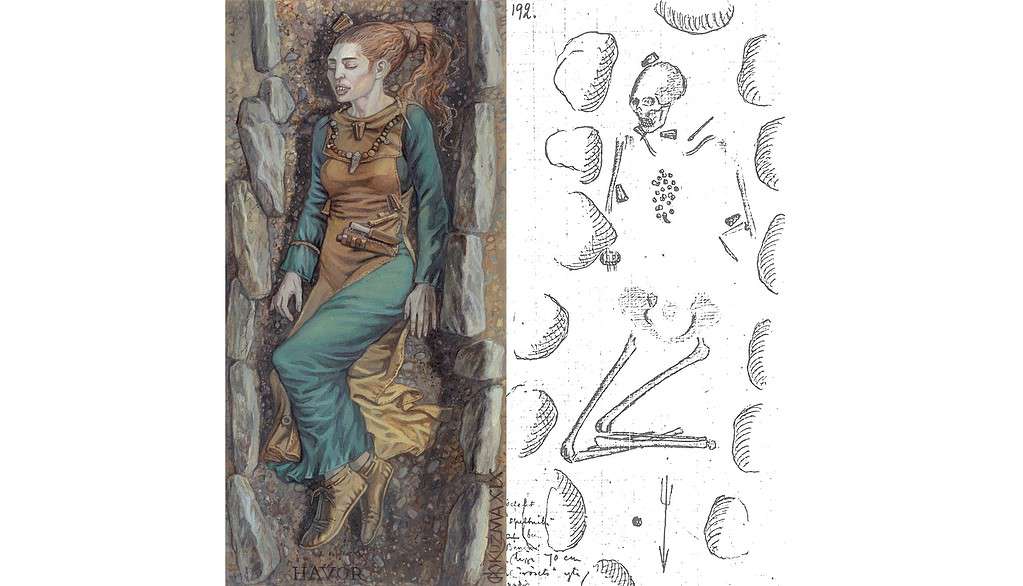

The researchers suggest that these women might have undergone this transformation as infants, possibly in regions around the Black Sea, where cranial modification was common. DNA analysis confirmed that the women originated from that region.

The exact reasons and methods behind their skull deformations remain unclear, but the implications are profound. Matthias Toplak believes that these altered skull shapes were likely seen as symbols of status and attractiveness within Viking society by virtue of their sheer exoticism.

This practice was likely performed by wrapping cloth tightly around infants’ heads or using wooden boards to shape the skull while the bones were still malleable. The process is not all that different from what some doctors use today to correct the skull shapes of babies with deformities. However, the current process is a bit more modern. Typically, babies are fitted with a plastic helmet that very slowly and painlessly reshapes flat spots over time as their brains grow.

“Cranial modification has long piqued the interest of anthropologists and craniofacial surgeons,” Goldstein told Atlas Obscura. “Modifications have been recorded in various cultures throughout history, including the Mesoamerican, Native American, Eurasian, and now, Viking people.”

Cultural Significance and Mysteries

While modern techniques aim to correct skull deformities in infants, historical practices aimed to achieve a specific aesthetic or cultural ideal. In many cases, elongated skulls were a sign of social status, indicating nobility or the elite of society. In others, they improved beauty, or they had religious or cultural significance linked to local mythology or identity.

Archaeological finds have provided significant information about this practice. For example, in Peru, the Paracas skulls are some of the most extreme examples of cranial deformation. Some skulls were elongated to an almost alien appearance. Similarly, in Europe, the Huns and the Alans are known to have practiced skull elongation, which has been found in numerous archaeological digs. In Egypt, the discovery of a mummy, supposedly of Akhenaten, said that the tradition may have also been present among the Egyptian pharaohs.

It’s not known if the practice had any impact on the cognitive abilities of Viking women, nor is it clear why it was done initially. Considering skull elongation is extremely uncommon among Vikings, the researchers think it is due to trade and a type of cultural influence. In any case, the discovery challenges previous ideas about Viking beauty practices and emphasizes the intricate relationship between culture, identity, and physical appearance throughout human history.

“It is still not completely clear if the deformed skulls were meant to represent a certain beauty ideal or if they were meant to show belonging to an elite or a specific social group,” Toplak said to Atlas Obscura. “It's possible that all these factors came together, and the deformed skulls were a way to indicate social elite status and, inevitably, attractiveness.”

The findings were published in the Current Swedish Archaeology.