Researchers at Linköping University in Sweden have successfully made extremely thin sheets of gold for the first time. This new material, named 'goldene,' has different properties that could be useful in various applications like environmental catalysis and advanced electronics.

Creating 2D gold

The development of goldene is a significant achievement in the field of materials science. It's usually difficult to make such thin layers because gold atoms tend to clump together naturally. The scientists used an old Japanese method and modified it to fit modern scientific needs.

During the process, the scientists changed some of the properties of gold. For example, gold is usually a good electrical conductor, which is why it's used in electronic devices like phones and computers.

However, when it's reduced to a single sheet that's only one atom thick, gold (or goldene) becomes a semiconductor. This 2D material shows extraordinary properties, similar to graphene at a single-layer thickness. graphene exhibits extraordinary properties at a single-layer thickness, so does this 2D material.

“Since the discovery of graphene, 2D materials have gained interest for their extraordinary properties. Diverse 2D materials comprising non-metallic elements or covalently bonded blends have been investigated. However, the synthesis of 2D materials solely comprising metals is challenging,” the researchers told ZME Science in an email.

“Goldene is one of few elemental 2D materials comprising metals, which are produced via scalable methods. Metals, especially noble metals such as gold due to their plasmonic properties, are used in a wide range of applications such as chemical, biological, pharmaceutical, and electrical applications. Thus, goldene would find unique applications different from those of other 2D materials,” they added.

A Serendipitous Discovery

The journey to goldene began unexpectedly and had many twists and turns. The researchers were working with a special conductive ceramic called titanium silicon carbide, and they added gold to the bulk material at high temperature to enhance its conductivity. However, they were surprised to find that atomic layers of gold replaced silicon within the ceramic matrix, creating titanium gold carbide — a precursor to goldene.

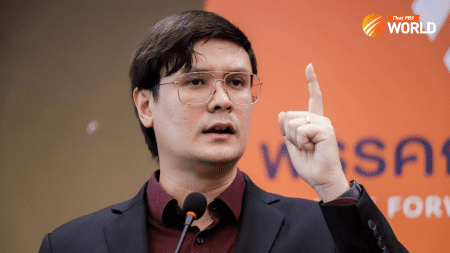

These developments took place years ago, as a result of pioneering work led by Lars Hultman, Professor of Thin Film Physics at Linköping University. The researchers knew they were on to something valuable if they could figure out how to peel off that 2D layer and extract the atomic gold.

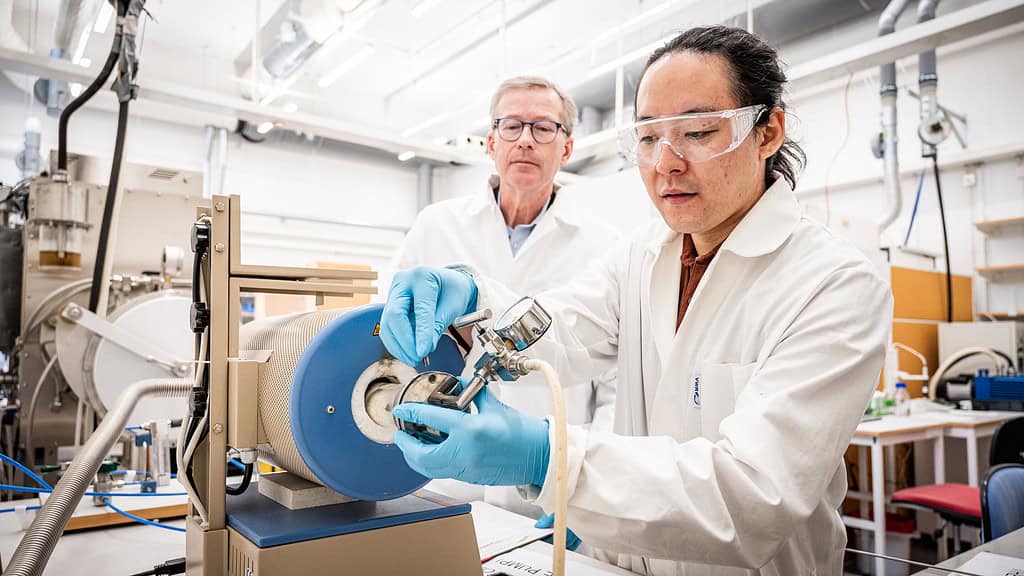

The breakthrough came when Shun Kashiwaya joined the group as a researcher at the Materials Design Division at Linköping University. With Kashiwaya’s assistance, the researchers adapted a century-old Japanese technique using Murakami’s reagent. This method was originally used for removing carbon residues in knife-making, but they applied it to separate the titanium carbide from the titanium gold carbide.

This process was complicated. It involved adjusting different concentrations of Murakami’s reagent over various periods. Despite this, they found a suitable dilution for the reagent after many attempts. They also discovered that performing the etching process in complete darkness was crucial. Light causes the formation of cyanide ions from the reagent, which attack the gold. Finally, the researchers added surfactants to prevent the resulting golden sheets from curling and coming together.

Potassium ferricyanide may be harmful, so it must be handled with great care. However, the researchers explain that their method involves diluting this reagent to less than one percent in the solution, reducing its impact. Additionally, the cyanide ions stay enclosed in the reagent’s molecules without being released.

Uncovering the Potential of Goldene

Using an electron microscope, the researchers verified goldene’s distinctive structure, which is characterized by having two available bonds in its two-dimensional form, thereby boosting its chemical reactivity. This makes it suitable as a catalyst for uses in converting carbon dioxide, producing hydrogen, and creating valuable chemicals.

Beyond the laboratory, the impact of goldene is significant. The material’s effectiveness in catalytic uses means that less gold is required for processes that currently rely on larger amounts of the metal. Furthermore, goldene also displays semiconductor properties, unlike its bulk form, enabling new applications for gold in technologies where traditional metals are not practical.

“To anticipate potential applications, we aim to explore the fundamental properties of goldene and optimize the synthetic process further to increase the goldene sheet area and yield. The current upper limit is the substrate wafer size of 200 mm. Furthermore, we envision applying this developed synthetic approach to exfoliate atomic sheets of other 2D noble metals beyond golden,” said the researchers looking toward the future.

The findings were published in the journal Nature Synthesis.