Cicadas go through an extraordinary life cycle. There are two types: annual and periodical. While annual cicadas show up every year, it's the periodical ones that are truly fascinating.

Periodical cicadas spend most of their lives underground as nymphs, only to emerge simultaneously across large areas after 13 or 17 years. This long phase, spent beneath the soil, is a growth period during which the nymphs feed on sap from tree roots.

The emergence of cicadas is a natural spectacle that changes the landscape. Male cicadas climb onto tree branches to sing together, creating a loud chorus to attract mates. After mating, female cicadas lay their eggs in tree branches. When the eggs hatch, the new nymphs fall to the ground and burrow into the soil, beginning the cycle again. Tree branches The combination of the spectacular cicada emergence and the lengthy waiting period makes a cicada spawning season significant in the eastern and midwestern United States. This year is special because both a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood will emerge at the same time. A “brood” is a scientific term for a group of cicadas that emerge simultaneously.

Sometime around mid-May, a massive number of cicadas will descend, especially upon Illinois. This is the first time since 1803 that two broods will emerge at the same time. The next double cicada event won’t happen until 2037.

The unique event of both a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood emerging simultaneously will take place around mid-May this year, bringing a huge number of cicadas, particularly to Illinois. This is the first time since 1803 that two broods will emerge at the same time. The next occurrence won’t happen until 2037.

The occurrence of two broods emerging simultaneously has not happened in over 200 years. The next double-cicada event won't take place until 2037.

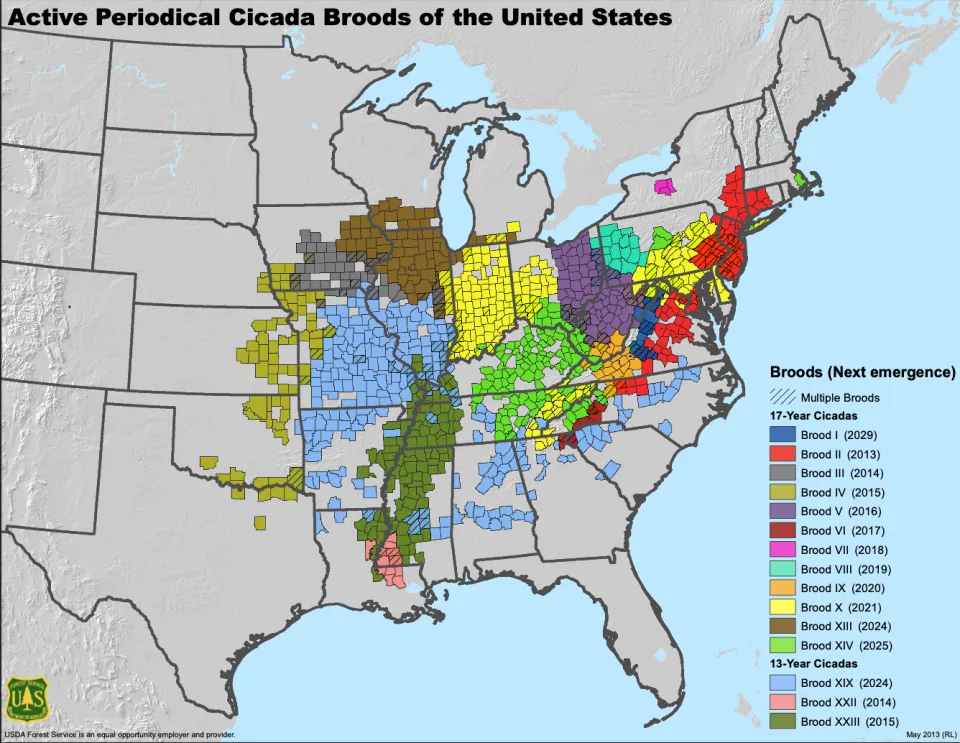

Map of dual cicada brood emerging in 2024. Source: The Cidada Project at the University of Connecticut/The Washington Post.

Broods are classified based on their geographical location and the timing of their emergence, each assigned a unique Roman numeral for identification. There are 15 identified broods of periodical cicadas in the United States. 12 of these are 17-year cicadas and 3 are 13-year cicadas.

These broods emerge in different years and geographical locations, often covering specific areas in the eastern and central United States. Over time, scientists and nature enthusiasts have thoroughly mapped the location and cycles of each brood, allowing them to predict when and where an emergence will occur.

This spring and early summer, Brood XIX (known as the Great Southern Brood) will appear in several states including Missouri, Arkansas, southern Illinois, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas, and surrounding states after hibernating for 13 years. Brood XIII, or the Northern Illinois Brood, will emerge from its 17-year cycle in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin. The next occurrence of both of these breeds emerging simultaneously won't happen for another 221 years.

The exact timing of when this will happen is not known. Once the insects are fully grown and the nearby soil reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit (17 degrees Celsius), the cicadas are ready to go.

The area where the two groups of cicadas overlap is not very large, which could be a good thing given the disturbance this may cause. Scientists are especially excited because it's so rare to see two separate populations of periodical cicadas emerge together. They will be particularly on the lookout for any interbreeding events and the potential outcomes.

The 13- and 17-year cicadas are distinct species, which explains their different cycle lengths. There are nine species of periodical cicadas, seven of which live in the United States, as part of the genus Magicicada. However, there are over 3,400 species of cicadas in the world, highlighting the unique nature of periodical cicadas.

Adult periodical cicadas usually measure about 1 to 1.5 inches (2.5 to 3.8 cm) in length. They have a striking black body that contrasts sharply with their bright red eyes. They have transparent wings with prominent veins, which they hold roof-like over their bodies when at rest.

A sound as loud as a jet engine

A trained observer can differentiate between the various species of cicadas. However, you don't have to be an entomologist to notice the difference between two different broods by listening. While the physical differences between species are very minor, the calls made by the male insects are distinct. Each brood produces a different set of songs, which the females recognize as their mating call.

The method behind their ability to produce such powerful sounds is a fascinating example of nature's clever design.

Male cicadas have a pair of specialized organs called tymbals, located on the sides of the abdominal base. The tymbal is a ribbed membrane that the cicada can rapidly contract and relax using a muscle. This action causes the tymbal to buckle inwards and then snap back to its original position, creating a click sound with each buckle. When these clicks are produced rapidly in succession, they generate the cicada's characteristic buzzing or singing sound. Cicadas are actually drawn to the vibrating sounds of power tools and lawnmowers, which resemble their songs.

The abdomen of the male cicada acts as a resonating chamber, amplifying the sound to levels that can exceed 100 decibels at a distance of 20 inches (50 cm) away in some species, making cicadas one of the loudest insects in the world.

While the possibility of trillions of cicadas appearing suddenly may sound threatening, there's no real need to worry. They don't sting or bite. They're not pests and apart from the noise (and the smell), they're not much of a nuisance. One thing's for sure, birds love them (for lunch).

The reason for the specific 13- or 17-year periods of cicadas that come out regularly is still up for debate. These prime numbers are believed to help them avoid matching up with the life cycles of potential predators, which helps them stay alive. When the cicadas finally appear, their synchronized arrival in large numbers makes it impossible for predators to eat all of them. prime numbers are thought to help avoid synchronization with the life cycles of potential predators, a strategy that enhances their survival. When cicadas finally emerge, their synchronized appearance in overwhelming numbers ensures that predators cannot possibly eat them all.

Apart from birds, mammals, reptiles, and even some fish like to eat these insects. As for us humans, we can be happy with the opportunity to witness their loud and magical spectacle.