Nada Hassanein | (TNS) Stateline.org

Elizabeth Bauer received a call at the gym from her fertility nurse last August. This call brought them the news they had been waiting for.

Elizabeth called Rebecca so they could hear together that they were expecting a baby.

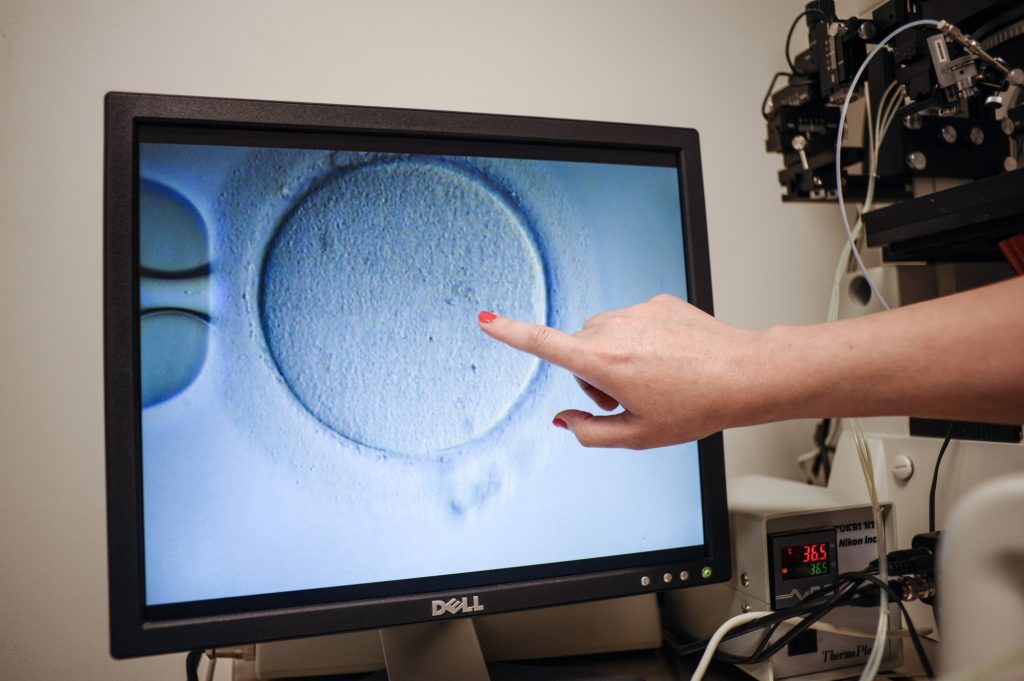

Three years ago, before their marriage, the couple decided they wanted to have a child. Both wanted to be involved in the pregnancy process. So, they used a process called reciprocal in vitro fertilization, in which eggs were taken from Rebecca and fertilized with donor sperm to create embryos. Then one of the embryos was implanted in Elizabeth’s uterus.

Although both Elizabeth, a 35-year-old teacher, and Rebecca, a 31-year-old consultant, had health insurance, it didn't cover the roughly $20,000 procedure, so they had to pay for it themselves.

But starting next year, health insurance providers in D.C. will have to pay for IVF for same-sex couples who can't conceive naturally. Only seven states (Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey and New York) have similar requirements. However, a new definition of “infertility” might lead other states to do the same.

In October, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine changed the definition of infertility. expanded The new definition of infertility includes all patients who need medical help to conceive, whether as a single parent or with a partner. Previously, the organization defined infertility as a condition in which heterosexual couples couldn’t conceive after a year of unprotected intercourse.

The group stressed that the new definition should not be used to deny or delay treatment to any individual, regardless of their relationship status or sexual orientation.

Dr. Mark Leondires, a reproductive endocrinologist and the founder and medical director at Illume Fertility and Gay Parents To Be, said the new definition could make a big difference.

He said, “It gives us extra power to say, ‘Listen, everyone who meets the definition of infertility, whether it’s an opposite-sex couple or same-sex couple or single person, who wants to have a child should have access to fertility services.’

At least four states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island) are currently considering broader IVF coverage mandates that would clearly include same-sex couples, according to RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association. Bills were introduced but did not progress in Oregon, Washington and Wisconsin.

A recent change in policy at the federal level might also add to the momentum. Earlier this month, the departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs extended IVF service benefits to patients regardless of marital status, sexual orientation or whether they are using donor eggs or sperm. The new policy follows a lawsuit filed in federal court last year. announced Betsy Campbell, RESOLVE’s chief engagement officer, said, “The federal government is the largest employer in the country, so if they’re providing these type of benefits, it definitely adds pressure on other employers and states to do the same.”

A total of 21 states

IVF involves gathering mature eggs from ovaries, using donated sperm to fertilize them in a laboratory, and then putting one or more of the fertilized eggs, or embryos, in a uterus. One complete cycle of IVF can take up to six weeks and can cost between $20,000 and $30,000. Many patients require multiple cycles before getting pregnant.

multiple cycles before becoming pregnant. Nearly 100,000 babies in the U.S. were born in 2021 through IVF and other forms of assisted reproductive technology, such as intrauterine insemination, according to

federal data IVF continues to attract nationwide attention following the Alabama Supreme Court’s.

ruling last month that under state law, frozen IVF embryos are considered children, meaning patients or IVF facilities can face criminal charges for destroying them. The decision caused an uproar, and three weeks later Alabama Republican Gov. Kay Ivey signed a ruling into law that gives IVF clinicians and patients immunity from criminal and civil charges. bill Polly Crozier, director of family advocacy at GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, or GLAD, described the Alabama decision as “a shock to the system.” But Crozier said the reaction to it sparked a “bipartisan realization that family-building health care is important to so many people.”

Crozier commended the insurance requirements in Colorado, Illinois, Maine and Washington, D.C., for more explicitly including LGBTQ+ people. Maine’s

, for example, states that a fertility patient includes an “individual unable to conceive as an individual or with a partner because the individual or couple does not have the necessary gametes for conception,” and says that health insurers can’t “impose any limitations on coverage for any fertility services based on an enrollee’s use of donor gametes, donor embryos or surrogacy.” lawChristine Guarda, financial services representative at the Center for Advanced Reproductive Services at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, said more same-sex couples are seeking help starting families. One reason, she said, is that more large employers that provide insurance directly to their employees, such as

, are including broad IVF coverage. Amazon‘Elective procedure’?

But some lawmakers are doubtful about broadening the definition of infertility to include same-sex couples. That was evident at

bill earlier this month, where Republican state Rep. Cara Pavalock-D’Amato noted that “infertility isn’t necessarily elective, but having a baby is.” a hearing on the Connecticut “Now, we are changing definitions to cover elective procedures,” Pavalock-D’Amato said. “If we’re changing the definition for this elective procedure, then why not others as well?”

She added: “Infertility, whether you are straight or gay, up to this point has been a requirement. Now, is it through this bill that we are no longer requiring people to be sick? They no longer have to be infertile?”

But supporters of the change say that making IVF coverage available to same-sex couples is a matter of fairness.

“I don’t think anyone in the LGBTQ community is asking for more. They’re just asking for equal benefits, and it's discriminatory to say, ‘You don’t get the same benefit as your colleague simply because you have a same-sex partner,’” Leondires said in an interview.

“If you’re contributing to the same health care system as the person sitting next to you, then you should receive the same benefit,” he said.

Elizabeth and Rebecca Bauer, who are busy decorating a nursery and buying baby clothes, acknowledge that they were fortunate to afford IVF even without insurance coverage, and that “there are plenty of people who don’t have the time or the means.”

“There are so many ways that people who want to start a family might face challenges,” Elizabeth said, adding that the previous infertility definition felt like a “pretty impossible barrier” for non-straight couples. “Insurance should make starting a family possible for any person or persons who desire to do so.”

States Newsroom

Stateline is part of , a national nonprofit news organization focused on state policy.©2024 States Newsroom. Visit at

stateline.org . Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.The American Society for Reproductive Medicine expanded the definition of infertility to include all patients who require medical intervention, such as use of donor gametes or embryos, to conceive as a single parent or with a partner.