Arthur Allen | KFF Health News (TNS)

In January 2021, Carol Rosen received standard treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Sadly, she passed away three weeks later due to severe side effects from the drug meant to extend her life.

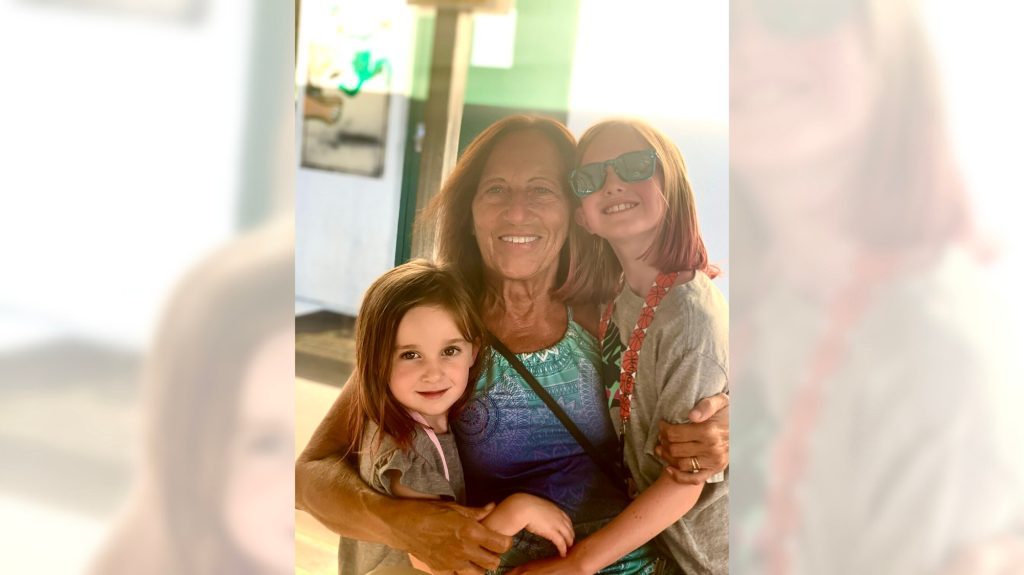

Rosen, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher, spent her final days in extreme pain, struggling with severe diarrhea, nausea, mouth sores, and skin peeling. Her kidneys and liver failed, and she suffered from internal burns. Lindsay Murray, Rosen’s daughter, described her agony.

Rosen was just one of over 275,000 cancer patients in the United States who receive fluorouracil, known as 5-FU, or its similar pill form capecitabine. These chemotherapy drugs, when given to patients lacking a specific enzyme, can cause severe suffering or even death.

-

A photo of Carol Rosen and her granddaughters at an Irish Cottage restaurant in Methuen, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, Rosen endured excruciating final days after receiving incompatible drugs during chemotherapy. (Lindsay Murray/TNS)

-

Carol Rosen and her daughter, Lindsay Murray, celebrating Thanksgiving in 2020. Rosen, a 70-year-old retired school teacher, experienced terrible days after receiving incompatible drugs during chemotherapy. (Justin Murray/TNS)

-

Carol Rosen and her daughter, Lindsay Murray, at Boston’s Fenway Park in 2020. Unfortunately, Rosen endured excruciating final days after receiving incompatible drugs during chemotherapy. (Lindsay Murray/TNS)

Expand

These patients essentially overdose on the drugs, as they remain in their bodies for prolonged periods instead of being swiftly metabolized and excreted. As a result, the drugs claim an estimated 1 in 1,000 lives on average annually , causing severe illness or hospitalization in 1 in every 50 patients. Physicians can conduct tests to detect the deficiency and receive results within a week. Based on the results, they can switch drugs or adjust the dosage for patients at risk due to genetic variations.

However, only 3% of U.S. oncologists regularly request these tests before administering 5-FU or capecitabine, largely due to the guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which do not recommend preemptive testing. Additional warnings about the lethal hazards of 5-FU were recently added to the drug’s label on March 21 following inquiries from KFF Health News. However, the administration did not make it mandatory for doctors to conduct the test before prescribing the chemotherapy.

The FDA The FDA, which is currently working on expanding its supervision of laboratory testing, stated during a House hearing

The agency, on March 21 that it could not endorse the 5-FU toxicity tests since it had not evaluated them. Daniel Hertz, an associate professor at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy, mentioned that the FDA generally does not review most diagnostic tests. He and other medical professionals have been urging the FDA for years to include a black box warning on the drug’s label, advising prescribers to test for the deficiency. “The FDA has a responsibility to ensure that drugs are used safely and effectively,” he stated. He said that not warning about the risks is a failure to fulfill that responsibility.The update is a step in the right direction, but not the significant change we need,” he said.

Europe is leading in terms of safety measures.

Since 2020, British and European Union drug authorities have advised the testing. A small but increasing number of U.S. hospital systems, professional groups, and health advocates, including the American Cancer Society, also support regular testing. Most U.S. insurers, both private and public, will cover the tests, which Medicare reimburses for $175, although the cost may vary depending on the number of variants screened.

its most recent recommendations

In their guidance on colon cancer, the Cancer Network panel pointed out that not everyone with a risky gene variant gets sick from the drug. They also mentioned that giving lower doses to patients with such a variant could deprive them of a cure or remission. Many doctors on the panel, including Wells Messersmith from the University of Colorado, have stated that they have never seen a 5-FU related death.

In European hospitals, it's common to start patients with a half- or quarter-dose of 5-FU if tests show they metabolize the drug poorly, then increase the dose if the patient responds well. Advocates of this approach argue that American oncology leaders are unnecessarily slow in adopting it, thereby harming people.

In “I think it’s the resistance of people on these panels, the mindset of ‘We are oncologists, drugs are our tools, we don’t want to go looking for reasons not to use our tools,’” said Gabriel Brooks, an oncologist and researcher at the Dartmouth Cancer Center. Oncologists are used to the toxicity of chemotherapy and usually have a “no pain, no gain” attitude, he said. 5-FU has been in use since the 1950s.

However, “anyone who has had a patient die like this will want to test everyone,” said Robert Diasio of the Mayo Clinic, who helped conduct a key study on the genetic deficiency in 1988.

major studies

of the genetic deficiency in 1988.

Oncologists often use genetic tests to match tumors in cancer patients with the expensive drugs used to shrink them. But the same cannot always be said for gene tests aimed at improving safety, said Mark Fleury, policy director at the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network. A test that can determine whether a new drug is suitable receives a lot more support for required testing,” he said. “The same stakeholders and forces are not involved in the case of a generic like 5-FU, first approved in 1962

, and costing

approximately $17 for a month’s treatment Medical advancements, many of them funded by taxpayers, are slow to be implemented in fields beyond oncology. For example, few cardiologists conduct tests on patients before prescribing Plavix, a brand name for the anti-blood-clotting agent clopidogrel, even though it fails to prevent blood clots as intended in a quarter of the 4 million Americans prescribed it annually. In 2021,the state of Hawaii was awarded an $834 million judgment from drugmakers it accused of falsely advertising the drug as safe and effective for Native Hawaiians, over half of whom lack the primary enzyme to process clopidogrel..

The numbers of people with the deficiency in the fluoropyrimidine enzyme are smaller, but those with the deficiency aren't at severe risk. aren’t at severe risk if they use topical cream forms of the drug for skin cancers, the risk is lower. However, even a single miserable, medically caused death was significant to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where Carol Rosen was among over 1,000 patients treated with fluoropyrimidine in 2021.

After Rosen’s death, her daughter was filled with grief and anger. She said, “I wanted to sue the hospital. I wanted to sue the oncologist,” Murray said. “But I realized that wasn’t what my mom would want.” Instead, she wrote Dana-Farber’s chief quality officer, Joe Jacobson, urging routine testing. He responded the same day, and the hospital quickly adopted a testing system that now covers more than 90% of prospective fluoropyrimidine patients. About 50 patients with risky variants were detected in the first 10 months, Jacobson said. Dana-Farber uses a Mayo Clinic test that looks for eight potentially dangerous variants of the relevant gene. Veterans Affairs hospitals use a 11-variant test, while most others check for only four variants.

It may be necessary to use different tests for different ancestries.

The more variants a test screens for, the better the chance of finding rarer gene forms in ethnically diverse populations. For example, different variants are responsible for the worst deficiencies in people of African and European ancestry, respectively. There are tests that scan for hundreds of variants that might slow metabolism of the drug, but they take longer and cost more.

These are bitter facts for Scott Kapoor, a Toronto-area emergency room physician whose brother, Anil Kapoor, died in February 2023 of 5-FU poisoning.

Anil Kapoor was a well-known urologist and surgeon, an outgoing speaker, researcher, clinician, and irreverent friend whose funeral drew hundreds. His death at age 58, only weeks after he was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer, stunned and infuriated his family.

In Ontario, where Kapoor was treated, the health system had just begun testing for four gene variants discovered in studies of mostly European populations. Anil Kapoor and his siblings, the Canadian-born children of Indian immigrants, carry a gene form that’s apparently associated with South Asian ancestry.

Scott Kapoor supports broader testing for the defect — only about half of Toronto’s inhabitants are of European descent — and argues that an antidote to fluoropyrimidine poisoning, approved by the FDA in 2015, should be on hand. However, it works only for a few days after ingestion of the drug and definitive symptoms often take longer to emerge.

an antidote to fluoropyrimidine poisoning

, approved by the FDA in 2015, should be on hand. However, it works only for a few days after ingestion of the drug and definitive symptoms often take longer to emerge.

Most importantly, he said, patients must be aware of the risk. “You tell them, ‘I am going to give you a drug with a 1 in 1,000 chance of killing you. You can take this test. Most patients would be, ‘I want to get that test and I’ll pay for it,’ or they’d just say, ‘Cut the dose in half.’” Alan Venook, the University of California-San Francisco oncologist who co-chairs the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, has led resistance to mandatory testing because the answers provided by the test, in his view, are often murky and could lead to undertreatment.“If one patient is not cured, then you give and you take away,” he said. “Maybe you took it away by not providing enough treatment.”

Instead of testing and potentially reducing a first dose of curative therapy, “I lean towards the latter, admitting they will get sick,” he said. About 25 years ago, one of his patients died from 5-FU toxicity and “I regret that deeply,” he said. “But unhelpful information may lead us in the wrong direction.”

In September, seven months after his brother’s death, Kapoor was boarding a cruise ship on the Tyrrhenian Sea near Rome when he happened to meet a woman whose husband, Atlanta municipal judge Gary Markwell, had died the year before after taking a single 5-FU dose at age 77.

“I was like … that’s exactly what happened to my brother.”

Murray senses momentum towards compulsory testing. In 2022, the Oregon Health & Science University

paid $1 million

to settle a lawsuit after an overdose death.

“What’s going to break that barrier is the lawsuits, and the big institutions like Dana-Farber who are implementing programs and seeing them succeed,” she said. “I think providers are going to feel kind of pressured into a corner. They’re going to continue to hear from families and they are going to have to take action.” KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs of

— the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.)

(©2024 KFF Health News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. A recent survey found that only 3% of U.S. oncologists routinely order the tests before dosing patients. KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.)

©2024 KFF Health News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.