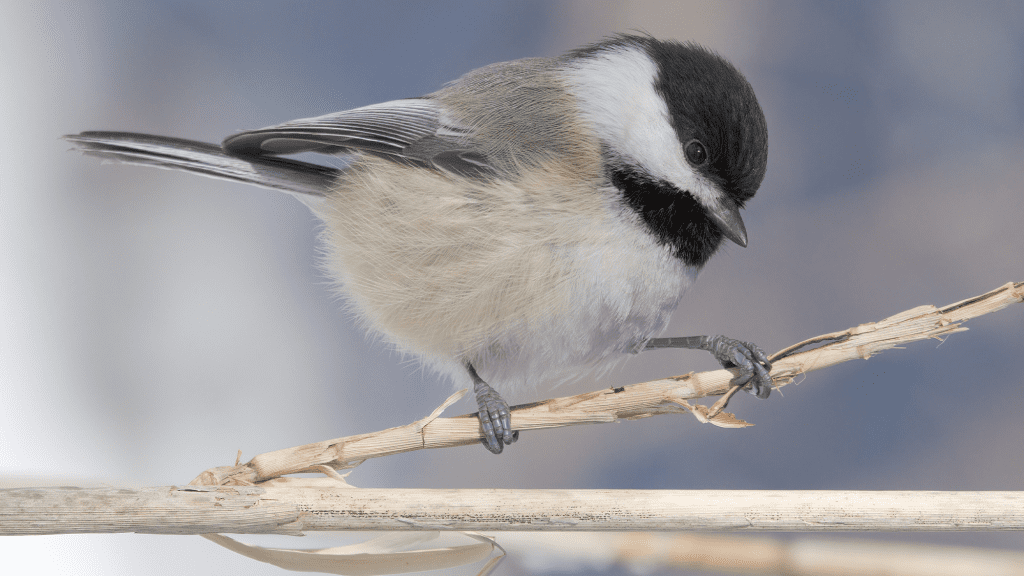

The brain’s capability to produce and retain memories is quite unknown. Memory isn’t always reliable, yet it’s crucial for survival. Remembering where food is stored during scarce winter months is a necessity for many animals, including black-capped chickadees. Recent research suggests that these birds with outstanding memories use a system similar to something seen at the store. They seem to remember each food location using brain cell activity that works like a barcode. The findings are detailed in a study released on March 29 in the journal Cell.

“We understand the world through our memories of objects, places, and people,” study co-author and Columbia University neuroscientist Dmitriy Aronov stated in a release. “Memories completely shape how we perceive and interact with the world. By studying this bird, we have a way to comprehend memory in a greatly simplified manner, and by understanding their memory, we will learn something about ourselves.”

‘Memory experts’

Scientists have long known that the brain’s hippocampus is essential for storing episodic memories such as where a car is parked or food is kept. It’s been more challenging to understand how these memories are stored in the brain, since it’s hard to know what an animal might be recalling at a specific time.

To address this challenge, the new study examines black-capped chickadees. Arnov refers to these birds as “memory experts” and masters of episodic memory. Most chickadees reside in colder areas and don’t migrate in the winter like other birds. Their survival depends on remembering where they stashed food in the summer and fall, with some birds creating up to 5,000 of these stashes daily.

[Related: Dogs and wolves remember where you hide their food.]

“Each cache is a well-defined, obvious, and easily noticeable moment in time during which a new memory is formed,” stated Aronov. “By focusing on these special moments in time, we were able to identify patterns of memory-related activity that had not been noticed before.”

A hippocampal ‘barcode’

In the study, the team constructed indoor arenas in a lab that were inspired by the birds’ natural habitats. During the experiments, a black-capped chickadee instinctively concealed sunflower seeds in the holes in the arenas, while the team monitored the activity in the bird’s hippocampus, using an implanted recording system. This tool allowed the team to monitor the brain while the birds moved freely and was removed between recording sessions. Concurrently, six cameras recorded the chickadees as they flew and an artificial intelligence system that automatically tracked them as they stashed and retrieved seeds.

“These are very noticeable patterns of activity, but they’re very brief—only about a second long on average,” study co-author and postdoctoral research fellow Selmaan Chettih stated in a release. “If you didn’t know exactly when and why they happened, it would be very easy to miss them.”

They observed that the hippocampal neurons fired in a unique pattern each time the chickadees stored food in a certain location. Each memory was marked with a unique pattern in the hippocampus that activated when the bird retrieved the cached food. The team referred to these patterns as barcodes since they are very specific labels of individual memories.

Aronov said that even if two nearby caches have different barcodes, the barcodes themselves are not related.

These barcode-like patterns occur separately from other activities of hippocampal neurons known as place cellsThese cells store memories of locations in the brain. Each of these pseudo barcodes remains unique, even for stashes hidden in the same place but at different times, or near stashes made in quick succession.

Aronov explained that many studies on the hippocampus have concentrated on place cells, which led to the Nobel Prize being awarded for their discovery in 2014. Nobel Prize was given in 2014 for the discovery of place cells.Aronov added, "The assumption in the field was that episodic memory must have something to do with changes in place cells. We find that place cells don’t actually change when birds form new memories. Instead, during food caching, there are additional patterns of activity beyond those seen with place cells."

The implications of this for humans

According to the teamThe team noted that it is not fully clear whether the chickadees activate the ‘barcodes’ and use those memories to make decisions about where to go next.

[Related: Do cats and dogs recall their past?]

In the future, the team hopes to observe whether the birds activate these barcode-like patterns when searching for caches in more remote spots or in more complex environments. They also plan to monitor brain activity while the birds decide which cache to visit.

The team is also keen to find out if this barcoding strategy is widely used by other animals, including humans, as memory is a crucial part of the human experience.

Chettih stated, "Episodic memories of particular events are central to people's sense of self and how they define themselves. That’s what we’re trying to understand."