David Lauter | Los Angeles Times (TNS)

At the U.S. Supreme Court nowadays, liberal judges don't have much influence. The real conflicts mostly happen between the court's very conservative and its more traditional conservatives.

Tuesday’s dispute over abortion pills provided a great example, and it emphasized the importance of the 2024 presidential election for the court. In particular, it showed one of the ways a second term for former President Trump could significantly differ from his first, with big effects on abortion rights, among other subjects.

Abortion poses a threat to the GOP

The political situation surrounding the high court's dispute is clear: The politics of abortion continue to cause trouble for Republicans.

The GOP achieved a long-held aim in 2022 when the newly strengthened conservative majority on the court reversed Roe vs. Wade, the decision that had ensured abortion rights nationwide for almost fifty years. The court's decision in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health sent abortion policy back to the states, 15 of which now prohibit all or almost all abortions, with six more imposing strict limits.

Those bans have not been successful in reducing the number of abortions in the U.S., mostly because of the wide availability of abortion pills. But they have caused a lot of anger among voters, especially women, that has ruined Republican candidates in swing districts and states.

The most recent example came a few hours after the high court dispute, when a Democrat, Marilyn Lands, won a special election to fill a largely suburban state legislative district in northern Alabama. Lands had focused her campaign on reproductive rights.

Her overwhelming victory — a 25-point margin in a closely divided district — was the first test of voter sentiment since the Alabama Supreme Court’s ruling that frozen embryos created by in vitro fertilization should be considered children under state law, a decision that the state legislature hurriedly tried to overturn after furious voter reaction.

The conservative division

The lesson that many traditional conservatives have drawn from their election defeats is that the GOP should move away from opposing abortion. That may have influenced some of the Republican-appointed justices as they considered Tuesday’s challenge to the Food and Drug Administration’s rules that allow widespread dispensing of mifepristone: They treated the case like an unwelcome guest — to be ushered out as rapidly as possible with a stern admonition not to return.

To the judges on the very conservative side, it represented something else — a missed opportunity for now and a chance to set down markers for the future.

Representing the Biden administration, Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar argued that the antiabortion group seeking to overturn the rules lacked standing to bring the case.

Standing refers to the legal principle that to challenge a law or rule, you have to be affected by it — you can’t just have a generalized grievance.

The antiabortion doctors who brought the case claimed they were affected because at some point, one of them might be in an emergency room when a woman who had taken mifepristone would show up seeking treatment for heavy bleeding, which is an occasional effect of the drug. If that happened, they would be forced to choose between their conscientious objections to abortion and their duty to care for a patient, they argued.

Prelogar said those assertions are based on a long series of unlikely events that didn't come anywhere close to proving standing.

Most of the justices seemed to agree.

Even if the doctors had standing, the proper solution for their claim would be to affirm that they could not be forced to take part in an abortion — a right they already have under federal law, said Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch concurred. The case was 'a prime example of turning what could be a small lawsuit into a nationwide legislative assembly on an F.D.A. rule or any other federal government action,' he said. He didn't mean that as a compliment.

Gorsuch, of course, was appointed to the court by Trump. Another Trump appointee, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, also seemed doubtful that the doctors had standing. The third Trump appointee, Justice Brett M. Kavanugh, said very little, but the one question he asked suggested that he, too, would likely side with the FDA.

How Trump could prohibit abortion pills

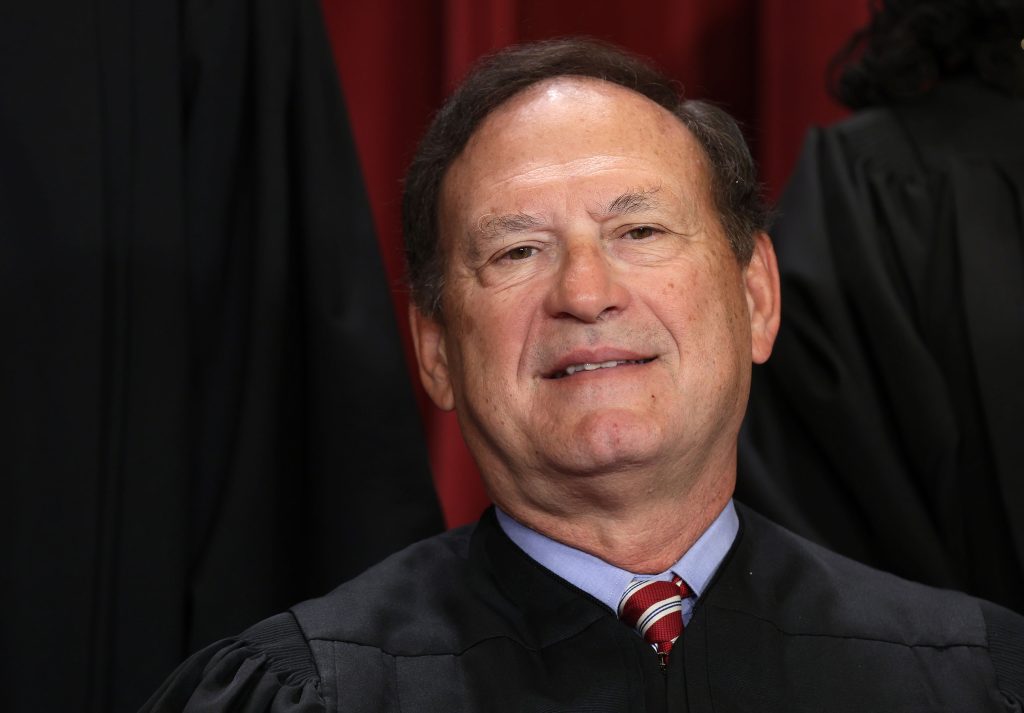

Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Clarence Thomas were the only members of the court who seemed receptive to the arguments presented by Erin Hawley, the lawyer representing the antiabortion group.

In their questions, both also returned to a related legal issue, the potential impact of an 1873 law known as the Comstock Act. That law, best known for prohibiting 'lewd' material from the mail, also prohibits any 'article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine, or thing which is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead another to use it or apply it for producing abortion'.

The law hasn't been enforced in decades, but up until the 1930s, it was repeatedly used to prosecute people for mailing birth control devices or even medical texts about contraception.

In 2022, the Justice Department issued a formal ruling that the law wasn't applicable to mifepristone because the drug has medical uses beyond abortion.

That ruling, however, could be reversed by a future administration. Antiabortion groups have made it clear that if Trump wins another term, they'll make the Comstock Act a high priority.

The Comstock law is 'quite extensive, and it explicitly covers drugs such as yours,' Thomas said at one point to Jessica Ellsworth, the lawyer representing Danco Laboratories, which manufactures mifepristone. His remark sounded like a warning.

Why two Bush justices, not Trump ones, make up the far right

The comments by Gorsuch and Barrett on one side and Thomas and Alito on the other highlighted a paradoxical reality of the current court: The justices Trump appointed to the court aren't the ones most likely to align with the MAGA movement's priorities. Instead, the far-right members, Thomas and Alito, were appointed by two figures of the pre-Trump GOP establishment — the Presidents Bush, father and son.

That doesn't mean that the three Trump appointees are moderates. They're firmly conservative. But they are establishment conservatives.

During Trump's tenure, the process of selecting and confirming Supreme Court justices was largely driven by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, working with Trump's White House counsel, Don McGahn. Trump had relatively little to do with it beyond confirming the final selections.

McConnell and McGahn sought justices who shared their beliefs, not necessarily Trump's.

By comparison, George H.W. Bush picked Thomas without knowing much about him. He wanted a Black judge to take the place of Justice Thurgood Marshall, and there weren't many Black Republican judges to choose from. The full extent of the new justice’s beliefs was unclear when he was selected.

Alito's background was more familiar when George W. Bush nominated him, but he wasn't the president's first preference. Bush attempted to appoint his adviser, Harriet Miers, to the court. However, he had to retract Miers’ nomination after facing strong opposition from the right. Selecting Alito was an attempt to limit political harm.

However, McConnell won't continue as the Senate Republican leader after this year — he's already announced his intention to step down. And Trump is unlikely to appoint someone to the White House staff like McGahn, who frequently obstructed him on important matters.

Trump's ability to stay in power is owed to the unwavering support of the right wing, particularly conservative, evangelical Christians. Any restrictions that the former GOP establishment managed to impose on him before would be largely absent in a second term.

Therefore, the primary lesson from Tuesday is this: the high court has already shifted considerably to the right, but it could move even further if Trump is reelected.

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.