By CAROLYN THOMPSON (Associated Press)

In Cleveland, seventh-grade student Henry Cohen was happily moving to the Beatles’ song “Here Comes the Sun” in teacher Nancy Morris’ classroom, swaying his arms across the planets on his T-shirt.

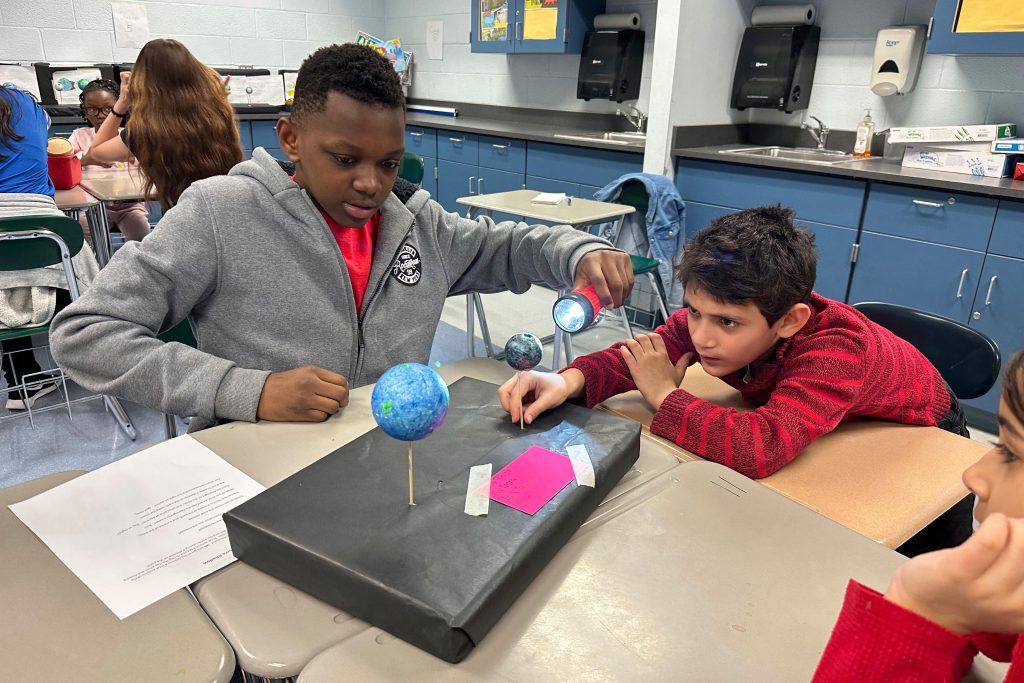

Henry and his classmates at Cleveland’s Riverside School were standing up and dancing during an activity related to April’s total solar eclipse. Second-graders who were invited to the lessons were sitting on the floor, laughing as they showed off their newly decorated eclipse viewing glasses. There were dioramas with small earth and moon models and flashlight “suns” on desks and shelves around the room.

Henry said his shirt showed his interest in space, which he described as “a cool mystery.” He said the eclipse was a rare event and he was happy to be able to experience it.

For schools in or near the path of the April 8 eclipse, the event has inspired lessons in science, literacy, and culture. Some schools are also organizing group viewings for students to observe the daytime darkness and learn about the astronomy behind it together.

A school system in Portville, New York, near the Pennsylvania line, plans to take its 500 seventh- through 12th-grade students to an old horse barn overlooking a valley, a bit out of the path of totality. There, they will be able to see the eclipse shadow as it arrives around 3:20 p.m. EDT.

The school day schedule had to be changed to remain in session, but Superintendent Thomas Simon said the staff did not want to miss out on this learning opportunity, especially at a time when students spend so much time looking at screens.

“We want them to leave here that day feeling they’re a very small part of a pretty magnificent planet that we live on, and world that we live in, and that there’s some real amazing things that we can experience in the natural world,” Simon said.

Schools in Cleveland and some other cities in the eclipse’s path will be closed that day to prevent students from being stuck on buses or in crowds. At Riverside, Morris came up with a mix of crafts, games, and models to educate and engage her students ahead of time.

“They really were not realizing what a big deal this was until we really started talking about it,” Morris said.

Learning about phases of the moon and eclipses is part of every state’s science standards, said Dennis Schatz, past president of the National Science Teaching Association. Some school systems have their own planetariums — relics of the 1960s space race — where students can watch educational shows about astronomy.

But there is no better lesson than the real thing, said Schatz, who encourages educators to use the eclipse as “a teachable moment.”

Dallas science teachers Anita Orozco and Katherine Roberts plan to do just that at the Lamplighter School. They arranged for the entire pre-K- through fourth-grade student body to watch the eclipse outdoors. The teachers spent a Saturday in March at a teaching workshop at the University of Texas at Dallas where they were told it would be “almost criminal” to keep students inside.

“We want our students to adore science as much as we do,” Roberts said, “and we just want them to comprehend and also be amazed by how incredible this event is.”

Handling young children may be a difficulty, Orozco said, but “we want it to be an occasion.”

In instructing future science teachers, University at Buffalo professor Noemi Waight has advised her student teachers to include how culture influences the way people experience an eclipse. Native Americans, for instance, may perceive the total eclipse as something sacred, she said.

“This is crucial for our teachers to comprehend,” she said, “so when they’re teaching, they can address all of these aspects.”

The STEM Friends Club from the State University of New York Brockport planned eclipse-related activities with fourth-grade students at teacher Christopher Albrecht’s class, hoping to convey their enthusiasm for science, technology, engineering and math to younger students.

“I want to demonstrate to students what is achievable,” said Allison Blum, 20, a physics major focused on astrophysics. “You know those prominent mainstream jobs, like astronaut, but you don’t really know what’s possible with the different fields.”

Albrecht sees his fourth-grade students’ interest in the eclipse as an opportunity to integrate literacy into lessons, too — perhaps even ignite a love of reading.

“This is is a great opportunity to read a lot with them,” Albrecht said. He has selected “What Is a Solar Eclipse?” by Dana Meachen Rau and ”A Few Beautiful Minutes” by Kate Allen Fox for his class at Hill Elementary School in Brockport, New York.

“It’s capturing their interest,” he said, “and at the same time, their imagination, too.”

___