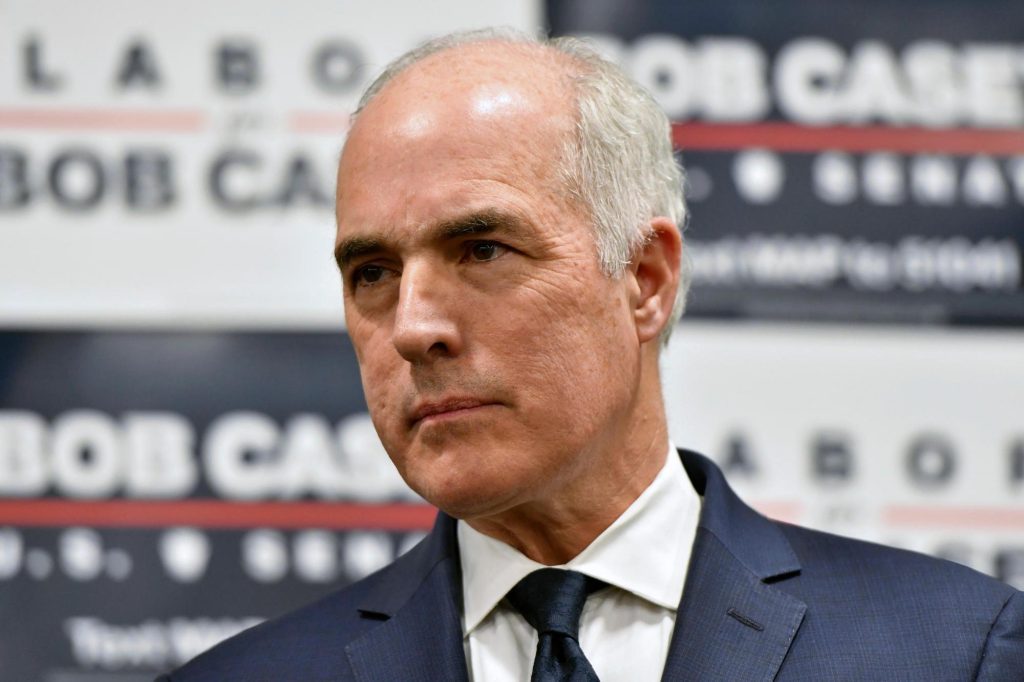

HARRISBURG — Democratic Sen. Bob Casey of Pennsylvania stood at the podium, leaning in close to the microphone, to emphasize his point to the union crowd about how upset corporate leaders are with him.

“But I have news for them,” Casey told Dauphin County Democrats and AFSCME members. “They should get used to it. Because I’m going to keep arguing about greedflation and shrinkflation.”

For Democrats trying to defend the White House and Senate majority, Casey is becoming the main figure in attacking “greedflation” — a blunt term for corporations that raise prices and cheat shoppers to maximize profits — and attempting to change the election-year story about the economy.

Rapidly increasing prices over the past four years have created a vulnerable point in 2024 for Democrats on a significant voter concern, with polls indicating that inflation is dragging down President Joe Biden in his attempt for a second term against Donald Trump.

It is perhaps no coincidence that Casey is trying to assist Biden by making the argument against greedflation in the critical presidential swing state he represents, where a victory for Democrats is crucial to maintaining the White House and Senate.

No Democrat has won the White House without Pennsylvania’s support since Harry S. Truman in 1948, and a Casey loss would likely ensure Republican control of a Senate currently divided by the narrowest of margins.

Casey, running for a fourth term, argues that consumer prices are high primarily because of greedflation, a term coined to target corporate profiteering at shoppers’ expense under the cover of inflation. Casey also is attacking greedflation’s cousin, “shrinkflation”: a seemingly covert way for companies to raise prices by slightly reducing product size, like shortening candy bars or putting fewer potato chips in the bag.

For Casey, the argument fits well with the populist politics that have made him a favorite of labor unions, and he has taken on the job with enthusiasm, seemingly spending more time attacking greedflation than his actual opponent in November, Republican David McCormick.

Inflation hit a four-decade high of 9.1% in 2022, more than enough to get the attention of consumers. And blaming greedflation for high prices is perhaps a powerful argument both to direct the anger of the squeezed wage earner and deflect Republican accusations that spending under Biden — including his $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package — caused higher prices.

McCormick, a former hedge fund CEO, calls Casey’s contentions “nonsense” and blamed federal spending under Biden and rising energy prices.

“This greedflation-shrinkflation thing is trying to distract the conversation about what really happened,” McCormick said in an interview.

Economists generally don’t subscribe to either side’s black-and-white explanation.

Instead, they tend to list many forces that played a role in global inflation during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, including pandemic-fueled supply-chain shortages worldwide, a strong labor market pushing up wages and Russia’s attack on Ukraine creating energy and food bottlenecks.

Prices in the United States are still approximately 20% higher on average than they were before the pandemic.

However, the government's mostly successful efforts to control inflation without causing a recession have not convinced people that credit is due, especially as food and housing prices continue to rise despite the overall slowdown in inflation rates.

The economy is the number one concern for many voters, and polls indicate that the impact of inflation is influencing how voters view President Biden, despite an improvement in their perception of the economy, according to Christopher Borick, director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion in Allentown.

Borick stated that he has seen evidence that voters may accept the argument that companies raised prices to take advantage of inflation. However, even if they do, voters may not necessarily give a pass to Biden and the Democrats.

“They are still feeling the effects of inflation, and their anger could be directed towards various scenarios,” Borick said.

Casey has made significant efforts to bring attention to the issue of greed-driven inflation.

He has released reports, sent strong letters to trade associations, appeared on national cable news shows, and introduced legislation directing the Federal Trade Commission to investigate price-gouging and unfair trade practices like shrinkflation.

“Many of these companies have said, ‘Well, consumers can simply choose not to purchase a certain product,’” said Casey in an interview. “When you go to the grocery store, you need to buy food every week. You need to buy household items regularly. You don’t have the option to delay purchases for six months. It's not like buying a new television set.”

During a visit to Pennsylvania in January, he discussed this with Biden, who subsequently criticized shrinkflation in a video released on Super Bowl Sunday and highlighted a social media post by the “Sesame Street” character Cookie Monster expressing dislike for shrinkflation.

In his State of the Union speech, Biden once again strongly opposed shrinkflation and pledged to crackdown on price gouging and “deceptive pricing.”

“Pass Bobby Casey’s bill and put an end to this,” Biden urged. “I really mean it.”

Then, in what is likely the first and only mention of Snickers candy in a State of the Union address, Biden added: “You probably all saw that commercial on Snickers bars. And you get charged the same amount, and you got about, I don’t know, 10% fewer Snickers in it.”

Mars Inc., the maker of Snickers, stated that they have not reduced the size of Snickers bars.

Casey's argument doesn't just involve political messaging and blame terminology.

It is based on a report released last year by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. In the report, Fed researchers claim that corporate profits accounted for 100% of overall inflation in the first year of the recovery and 41% of inflation in 2021-22 — a pattern similar to other recoveries in the last 70 years.

The Fed’s researchers described this as companies being “forward-looking” by raising prices in anticipation of higher costs.

In one common argument, Casey asserts that inflation increased by 14% from July 2020 through July 2022, while corporate profits rose by 75% — five times faster. Using federal data, Casey estimates that approximately $3,200 of the nearly $5,600 additional spending by the average American family in 2021 is a result of “corporate profit-taking.”

Some economists say that companies could be less limited by the normal competition during inflationary price increases, and could use temporary market power to increase profits.

The liberal economic advocacy group Groundwork Collaborative has put together a list of instances where corporate executives boasted about their profits or price hikes, and discussed issuing stock buybacks, raising dividends, or benefiting from high prices or high interest rates.

However, some researchers warn that the amount of profit-taking might be exaggerated.

Ahmed Rahman, an associate professor of economics at Lehigh University, stated that corporate profits have contributed to inflation, but he hasn't seen enough convincing evidence that greedflation plays a major role in inflation, let alone driving it.

Focusing on corporate profitability is “glib,” Rahman said. “It’s a little bit easy. It resonates during political cycles.”

Prices are not likely to decrease, according to Rahman and other economists, and it's more helpful for politicians to discuss the impact of upstream markets—like grain, oil, and computer chips—when addressing the price of consumer products such as potato chips or candy bars.

Moreover, even if corporations raised prices more than justified by costs, that's part of their job, said Z. John Zhang, director of the Penn Wharton China Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Instead of blaming the companies, he suggested blaming the decisions that resulted in inflation.

“It’s politics and this is really a matter of politicians trying to shift blame for policy-induced inflation,” Zhang said. “And obviously if I were in Biden’s position, that probably is a button I’m going to push, too. It seems to be believable.”