Nada Hassanein | Stateline.org (TNS)

Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave the green light to two groundbreaking gene therapies for sickle cell disease patients. Now, a new federal program aims to make these life-altering treatments accessible to patients with low incomes — and it may serve as a model for states to cover other costly therapies.

The new sickle cell treatments have brought hope to individuals dealing with this debilitating blood disorder, which is inherited and has a disproportionate impact on Black individuals. However, these therapies come with a hefty price tag of up to $3 million for a full treatment, which can last up to a year. Despite these high initial costs, cell and gene therapies have the potential to decrease healthcare expenses over time by addressing the root cause of the disease.

Through the Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model, the federal government will negotiate discounts with sickle cell drug makers Vertex Pharmaceuticals, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Bluebird Bio on behalf of state Medicaid agencies, which offer healthcare coverage to low-income patients. To take part, state Medicaid agencies must agree to prices based on these negotiations and commit to providing widespread access to the therapies.

The federal government stated that it will negotiate an “outcomes-based agreement” with the companies, meaning the prices for treatments will be linked to whether the therapy improves health outcomes.

If there are no in-state treatment facilities, Medicaid agencies would cover the cost for patients to receive the therapies in another state. Roughly 50% to 60% of sickle cell patients are on Medicaid, according to federal estimates. federal estimates.

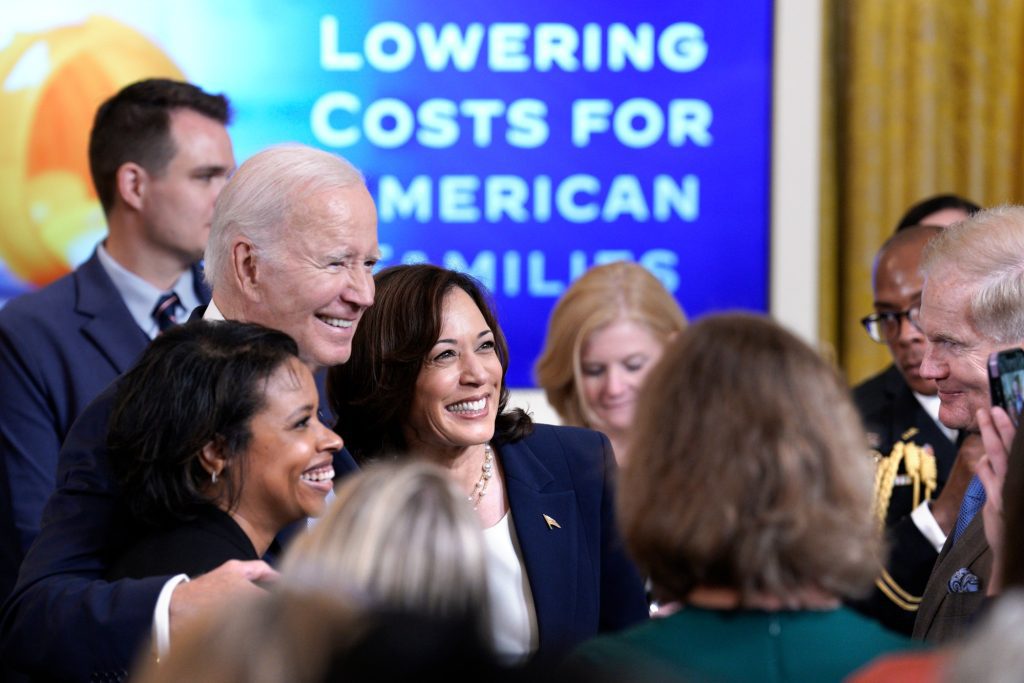

The federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) initiated the program in response to President Joe Biden’s 2022 executive order on lowering prescription drug prices.

CMS officials state that the framework will start with sickle cell disease treatments first, but other conditions may be included over time..

Numerous public health organizations, including the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy and the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, believe the new program could serve as a model for helping low-income patients afford other gene therapies.

Gene therapies, a quickly emerging type of treatment, aim to correct genes responsible for rare hereditary diseases. To date, the FDA has authorized treatments for a rare inherited eye condition and certain types of cancer, with more therapies in development.

Dr. Lakshmanan Krishnamurti, chief of pediatric hematology and oncology at Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven Hospital, referred to the model as “groundbreaking.”

“This is a government initiative to responsibly manage resources while ensuring access. From the perspectives of racial equity and health equity, it’s crucial that we make this work,” stated Krishnamurti, whose sickle cell patients have taken part in clinical trials testing gene therapies.

Some states, like Michigan, are choosing to create their own agreements with Bluebird Bio. The company mentioned it is in discussions with Medicaid agencies in 15 other states and is assessing the CMS framework. Bluebird spokesperson Jess Rowlands expressed that the company anticipates collaborating with the agency on an outcomes-based approach that allows access.

In a statement mentioned last week, Tom Klima, the company’s chief commercial and operating officer, stated, “Our commercial approach is based on the belief that people with sickle cell disease covered by Medicaid should have the same prompt access to gene therapy as patients with other types of insurance.”

During an earnings call last month, Vertex’s chief operating officer Stuart Arbuckle referred to the new model as an “important additional path to access.”

Who is impacted?

The majority of sickle cell patients in the U.S. are Black, but people of Hispanic, Middle Eastern and South Asian descent are also disproportionately impacted. There are various forms of sickle cell disease, but all of them affect hemoglobin, the protein inside red blood cells that carries oxygen. All forms of the disease cause the body’s red blood cells to be deformed.

The illness affects an estimated 100,000 Americans. It can lead to strokes, severe anemia and episodes of extreme pain, resulting in repeated hospitalizations. Those with sickle cell disease have a life span that is more than two decades shorter than the U.S. average.The estimated 100,000 Americans affected by the disease. more than 20 years shorter than the U.S. average. .

The two gene therapy treatments for sickle cell disease recently approved by the FDA, known as Casgevy and Lyfgenia, cost $2.2 million and $3.1 million per patient, respectively. The therapies require several other procedures — including chemotherapy before the treatments, which involve taking blood cells from a patient and modifying the DNA before reintroducing them into the body.

In Atlanta, Mapillar Dahn’s three daughters have sickle cell disease.

Her oldest daughter, Amatullaah Tyler, who is 20, was hospitalized earlier this month for another pain crisis. At the end of last year, she underwent a hip replacement due to avascular necrosis, which is the death of bone tissue due to lack of blood supply and a complication of the disease.

Sickle cell disease is a cause of stroke in children. Dahn’s 18-year-old daughter had her first stroke in second grade, causing neurocognitive and academic issues. She’s had more than 10 surgeries, including a brain surgery. Like her older sister, Dahn’s 14-year-old also suffered learning challenges after a series of ministrokes and is slated for the same brain surgery later this month. Both rely on monthly blood transfusions to prevent future strokes. leading Dahn, who founded the nonprofit patient advocacy group MTS Sickle Cell Foundation, also known as “My Three Sicklers,” said she wants Georgia to participate in the model.

Her oldest daughter isn’t currently eligible for the therapy because she is high risk. But Dahn is optimistic for her two younger daughters.

“The hope of it was overshadowed by the access to it,” Dahn said about the new gene therapy treatments. “The bulk of our patient community relies on [Medicaid] for payment. So, I think this is wonderful that they’re testing out this model to not only make it possible for patients to access, but in the long run to somehow make it more affordable.”

Tabatha McGee, leader of the Sickle Cell Foundation of Georgia, was part of a group that advised federal officials developing the program.

“We’re very thrilled because it is a step in the right direction,” she said. “This is something we absolutely want to come to reality. … We’ve never had a singular focus on sickle cell disease to help enhance the inefficiencies, to help enhance the inequality, inside of the health care system.”

In a statement, the Georgia Department of Community Health told Stateline it is reviewing the framework.

Expanding access

Dr. Lewis Hsu, head medical officer of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America, said the gene treatments are a creative option that don’t come with the same risks as a bone marrow transplant — the only procedure that may be able to “cure” sickle cell disease for some patients — since the treatment uses the body’s own stem cells and doesn’t require a match from another person.

“Having gene therapy available for sickle cell disease is just very thrilling,” Hsu said.

Reliable transportation is needed to start treatment. In a memo on state obligations, the federal government said states must ensure necessary transportation and travel expenses for both patients and their caregivers.

Hsu, who is also a professor of pediatrics and head of the Pediatric Sickle Cell Center at the University of Illinois Chicago, said transportation and lodging costs are important to consider, as patients come from all over the state or cross state lines to get treatment.

Federal officials told Stateline that multiple states have expressed interest in participating but wouldn’t say which ones.

Illinois’ Medicaid agency told Stateline it intends to participate.

“People with sickle cell disease often face obstacles to accessing treatments that can improve their health outcomes, including the high costs and geographic challenges,” said spokesperson Jamie Munks. “Expanding access to these high-cost treatments can significantly enhance the quality of life for people across Illinois who need them, and will contribute to a more equitable health care system overall.”

In Georgia, Democratic state Rep. Gloria Frazier told Stateline she is pushing her state Medicaid agency to enroll. But Frazier noted that because Georgia has not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, many patients would miss out.

“I am urging them to definitely participate in the process,” she said. “If we want to really help cure this disease, it has to be affordable.”

States Newsroom

Stateline is part of , a national nonprofit news organization focused on state policy.©2024 States Newsroom. Visit at

stateline.org . Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.A new federal program aims to make these life-changing treatments available to patients with low incomes — and it could be a model to help states pay for other expensive therapies.