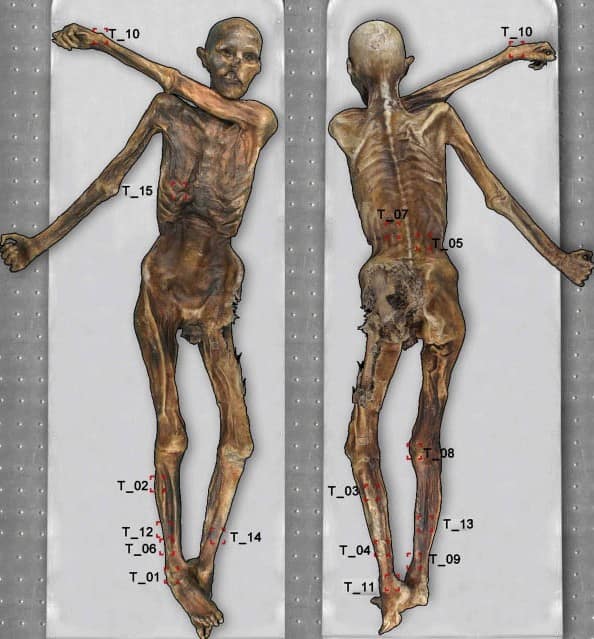

The mystery of Ötzi the Iceman’s tattoos has fascinated scientists and historians for many years. Ötzi, the European Tyrolean Iceman died and was buried under an Alpine glacier along the Austrian–Italian border around 3250 B.C. — and he had 61 tattoos across his body. These are the oldest tattoos in the world.

A recent study has now revealed the techniques used to create these ancient markings on the Iceman’s skin, providing insights into the life and culture of our ancestors.

Understanding Ancient Tattooing

Tattooing is an ancient craft, but its precise origins remain a mystery. Historical records trace tattooing back to Greece in the fifth century B.C., and possibly even earlier in China. Researchers have found evidence of tattooing in art, through tattoo tools, and on preserved human skin. Of these, mummified skin provides the most direct archaeological proof of ancient tattooing practices.

In 1991, Ötzi the Iceman was found in the Italian Alps, remarkably preserved for over 5,300 years encased in ice. We’ve learned many things about him since then. He was murdered, shot from behind with an arrow that pierced his left shoulder. The contents of his mummified stomach revealed he was killed just an hour after eating a final meal of dried ibex and deer meat with einkorn wheat. He wore a leather coat pieced together from the hides of several sheep and goats.

Plant remains from the crime scene suggest Ötzi traveled extensively during his last days. He would have ascended from about 600 meters (1,969 feet) in elevation to 3,210 meters (10,320 feet). In 2023, scientists examined his DNA revealing Ötzi had dark skin and was probably bald, challenging previous assumptions about his appearance.

One can look at this list of features and conclude Ötzi is probably the most studied mummy in the world. You wouldn’t be wrong. It’s thus rather surprising that we’ve only recently come to understand how one of Ötzi’s most visible features — his many tattoos — came to be.

Copper Age Ink

A collective effort among archaeologists, historians, and tattoo artists has led to a breakthrough in understanding these ancient symbols. Their research involved recreating Ötzi’s tattoos on modern skin using various ancient methods to determine which approach was most likely used.

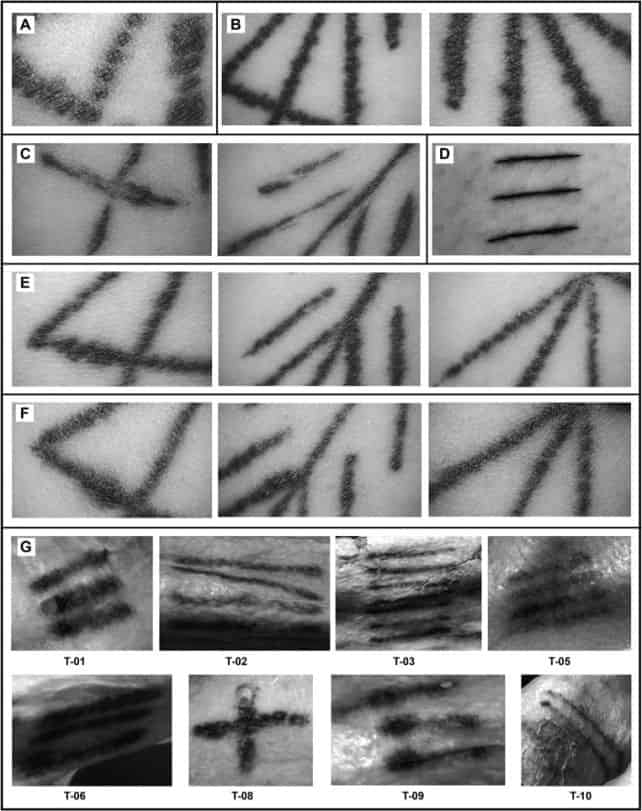

Previous studies have suggested four methods available to ancient tattoo artists: hand poking, subdermal tattooing, hand tapping, and incision. Most of Ötzi’s tattoos are short, straight lines, which suggests they were likely made by the incision method. This technique involves making a cut in the skin with a sharpened object, like a stone, and then inserting a coloring material, such as ash, into the wound.

In these situations, science requires testing. A New Zealand tattoo artist named Danny Riday offered to be the test subject. He tattooed his own leg with marks similar to those on the Iceman’s body using four different methods. Riday used various tools, such as animal bones, copper, obsidian, a modern steel needle, and even a boar tusk. Once they healed, these modern copies were compared to the ancient tattoos using detailed imagery.

A new way to look at things

The researchers discovered that the hand-poking method closely resembled Ötzi’s tattoos. This method involves using a sharpened stick dipped in ink to puncture the skin, resulting in a series of tiny, overlapping disks that combine to form a line. An animal bone or copper awl was likely used.

“Our findings show that there are noticeable differences in tattoos created using different tools and methods,” wrote the authors of the new study.

“This information may be used to study preserved remains from archaeological and museum collections, as well as to analyze historical imagery and traditions, to reveal previously unknown aspects of the associated cultures.”

The findings were reported in the European Journal of Archaeology.

Was this helpful?

Related Posts

- Scientists suggest a spacecraft that travels through Titan’s methane lakes

- How eye color is determined: from brown to blue

- Bioluminescent jellyfish earns Nobel Prize

- Researchers are improving water filtration techniques. We need them