Disease X has been making headlines in recent weeks as scientists, governments – and conspiracy theorists – get ready for the next pandemic.

However, one scientist warns that another pandemic is already here.

Bird flu.

The illness, named H5N1, appeared in domestic geese in China in 1997. It was mostly limited to southeast Asia in the following years, but quickly moved from birds to humans in the region, causing 40 to 50% of those infected to die.

Since 2020, the illness has spread rapidly, not just geographically, reaching from the Arctic to the Antarctic and every continent except Oceania, but affecting dozens of non-avian species.

'When people ask me what I think the next pandemic will be, I often say that we are in the midst of one – it’s just afflicting a great many species more than ours,' said Dr Diana Bell, professor of conservation biology at the University of East Anglia.

'I am referring to the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza H5N1, otherwise known as bird flu, which has killed millions of birds and unknown numbers of mammals, particularly during the past three years.'

Referencing a study released this month, Dr Bell observed that, since 2020, 26 countries have reported at least 48 mammal species that have died from the virus.

In January, a polar bear in Alaska became the first of its kind known to have died as a result of the disease.

Other animals to have caught the virus include brown bears, black bears, lynx and mountain lions.

'Not even the ocean is safe,' said Dr Bell, writing for The Conversation. 'Since 2020, 13 species of aquatic mammal have succumbed, including American sea lions, porpoises and dolphins, often dying in their thousands in South America.'

In March 2023, the first two dolphins to die of bird flu in UK waters were discovered at separate locations in Devon and Pembrokshire. They have not been the last.

Other UK mammals struck down by the disease include seals, otters and foxes.

But the disease hasn’t just spread to wild animals. Another mammal, humans, have also caught the virus.

Between January 1 and December 21 last year, there were 882 reported cases of bird flu in humans across 23 countries – of which 461, or 52%, were fatal.

'Of these fatal cases, more than half were in Vietnam, China, Cambodia and Laos,' said Dr Bell.

'Poultry-to-human infections were first recorded in Cambodia in December 2003. Intermittent cases were reported until 2014, followed by a gap until 2023, yielding 41 deaths from 64 cases. The subtype of H5N1 virus responsible has been detected in poultry in Cambodia since 2014.

'In the early 2000s, the H5N1 virus circulating had a high human mortality rate, so it is worrying that we are now starting to see people dying after contact with poultry again.'

Although the beginnings of Covid-19 have not been confirmed, one leading theory is a ‘zoonotic spillover’ event, as has happened with bird flu – when a virus passes from an infected animal to a person. The virus has not yet been transmitted from person to person, keeping the spread relatively limited, but bird flu is still considered by the World Health Organisation to be a major pandemic threat.

‘Scientists haven’t managed to completely sequence the virus in all affected species,’ said Dr Bell.

‘Research and continuous surveillance could tell us how adaptable it ultimately becomes, and whether it can jump to even more species. We know it can already infect humans – one or more genetic mutations may make it more infectious.’

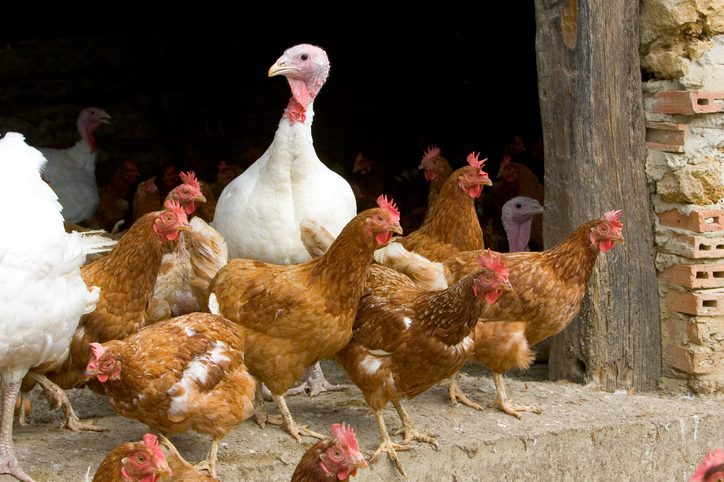

Right now though, the biggest danger is to the world’s bird populations.

‘The UK alone has lost more than 75% of its great skuas and seen a 25% decline in northern gannets,’ said Dr Bell. ‘Recent declines in sandwich terns and common terns were also largely driven by the virus.’

More than half a billion domestic birds have perished or been culled around the world as a result of the virus.

Millions more wild birds have been affected, including those already endangered, such as the African penguin and California condor. After 21 condors died, authorities began testing out a bird flu vaccine on the iconic birds.

But a global vaccination programme is not practical to combat this infectious and lethal disease.

As it continues to spread, Dr Bell argued the best step we can take is to change our attitude to farming.

‘How can we stem this tsunami of H5N1 and other avian influenzas?’ she said. ‘Completely overhaul poultry production on a global scale. Make farms self-sufficient in rearing eggs and chicks instead of exporting them internationally. The trend towards megafarms containing over a million birds must be halted in its tracks.

‘To prevent the worst outcomes for this virus, we must revisit its primary source – the incubator of intensive poultry farms.’