WASHINGTON — When the Pentagon formed the Space Development Agency five years ago, it faced strong opposition from traditional military satellite programs.

The agency was given a challenging yet controversial task: to create a new orbital structure for national security using small satellites and readily available technologies, overturning decades of preference for larger, expensive spacecraft that took years to develop and launch.

Many in the Air Force’s procurement ranks saw the idea as going against tradition, potentially harming the significant investments and contractor relationships in existing satellite programs.

However, five years later, the agency is launching the initial part of a low-Earth orbit group called the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture. It currently has 27 satellites in orbit and plans to launch more than 160 in the next 18 months.

“You’re going to upset some people and you’re not going to make friends, but that’s what you need to do to bring about change,” said Derek Tournear, the agency’s director. “And so far, it’s been successful.”

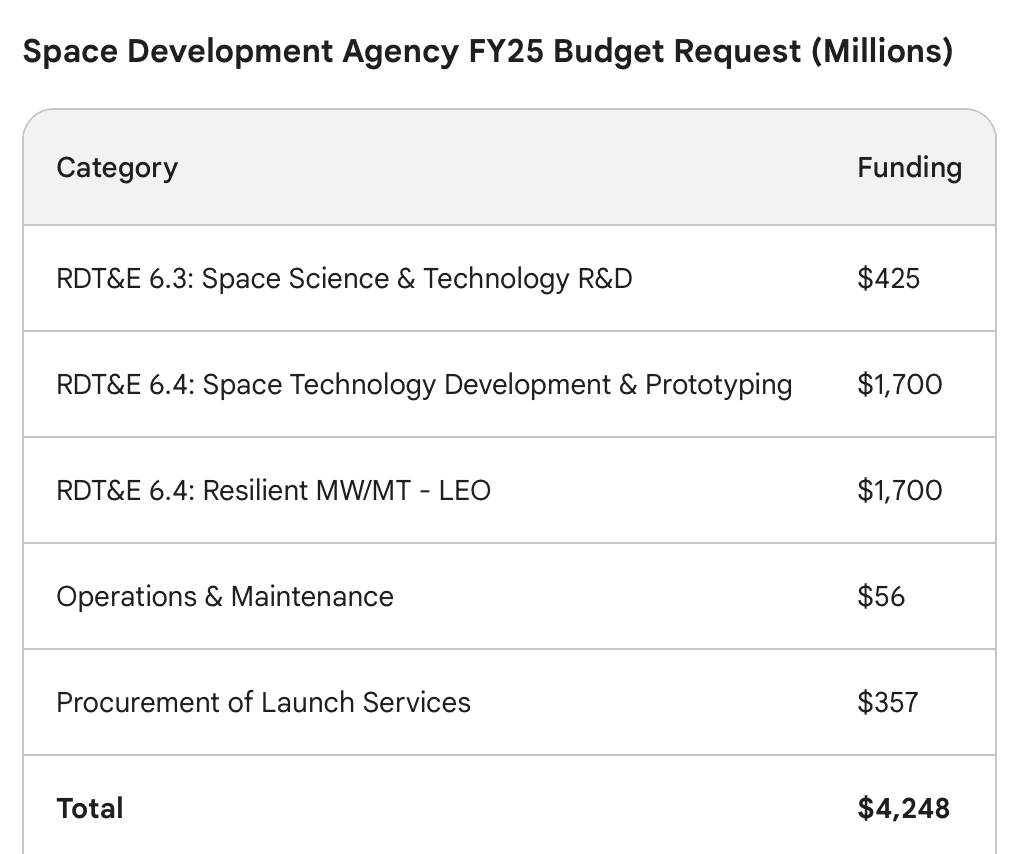

The Space Development Agency now has 322 employees and an annual budget of over $4.2 billion.

The agency is seen within the Pentagon — and now the Space Force, which was separated from the Air Force in December 2019 — as a model for a faster, more commercially oriented procurement and launch approach — possibly a pattern for how the military could revamp its purchasing more broadly.

During a recent interview with SpaceNews, Tournear acknowledged that the journey for the Space Development Agency has been far from smooth, with skeptics in the Pentagon and Congress initially unwilling to fund its first-year budget request.

A significant challenge for the Space Development Agency has been ensuring timely deliveries from suppliers due to ongoing disruptions in the supply chain resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It’s been challenging,” Tournear said. But he noted that companies are gradually getting back on track as bottlenecks ease. SDA program managers are in constant contact with vendors, he said, and the situation can change from day to day, particularly with lower-tier suppliers.

Another area of disagreement has been the agency’s insistence on using fixed-price contracting methods that oblige suppliers to meet a set cost — or take the risk of incurring additional costs themselves.

Some major defense contractors are reportedly avoiding fixed-price contracts, considering them too risky. But Tournear said companies are still eager to compete for SDA work because the agency requests advanced technologies that do not require risky development work.

The Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture includes a Transport Layer of data communications satellites that will function as a tactical network to transfer data collected by a Tracking Layer of infrared sensors to users across the globe. The Transport Layer satellites are estimated to cost between $14 million and $15 million each, and Tracking Layer satellites are expected to cost $42 million to $45 million per unit.

Those are competitive prices that include not just the production of fully integrated spacecraft but also launch and ground services, according to Tournear. They also show SDA's plan to reduce costs by making many spacecraft at the same time, using commercial areas.

‘New vendors coming in’

Tournear said he sees the Space Development Agency’s contracting opportunities as increasingly attractive for both traditional and commercial vendors, with “new vendors coming in every day” to bid on work.

While the agency has given large contracts to well-known defense companies like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and L3Harris, it has also made big orders with newer commercial manufacturers like York Space Systems.

Most recently, two of the agency’s high-stakes contracts for Tranche 1 of the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture were split between Lockheed Martin, L3Harris, and two relative newcomers to the national security satellite arena — Rocket Lab and Sierra Space.

“We actually saw a big increase in the number of proposals for that contract,” Tournear said. “I was surprised by the number of proposals that we saw. That really shows a market that’s healthy.”

Tranche 2 of the PSWA — scheduled to start launching in 2026 — is projected to have 300 satellites.