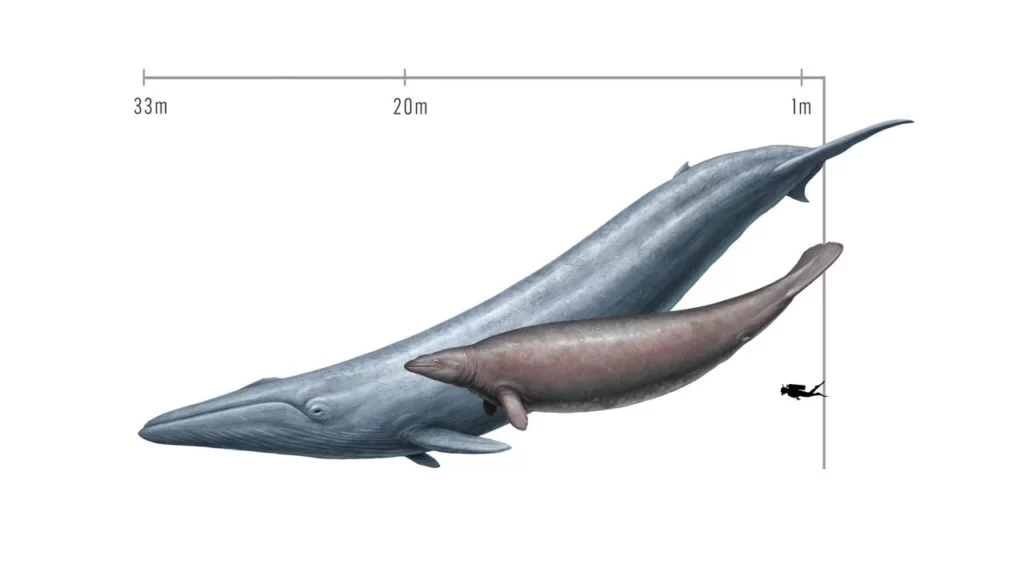

In 2023, a controversial discovery stunned paleontologists when researchers made the bold claim that a 39-million-year-old ancient marine mammal, known as Perucetus colossus, might have weighed between 180 and 340 metric tons. For reference, the largest blue whale ever discovered weighs around 175 tons. This would have made Perucetus colossus the the heaviest known animal in science. Additionally, since the ancient colossus was ten meters shorter than the blue whale, it would have certainly been the densest animal by a long shot.

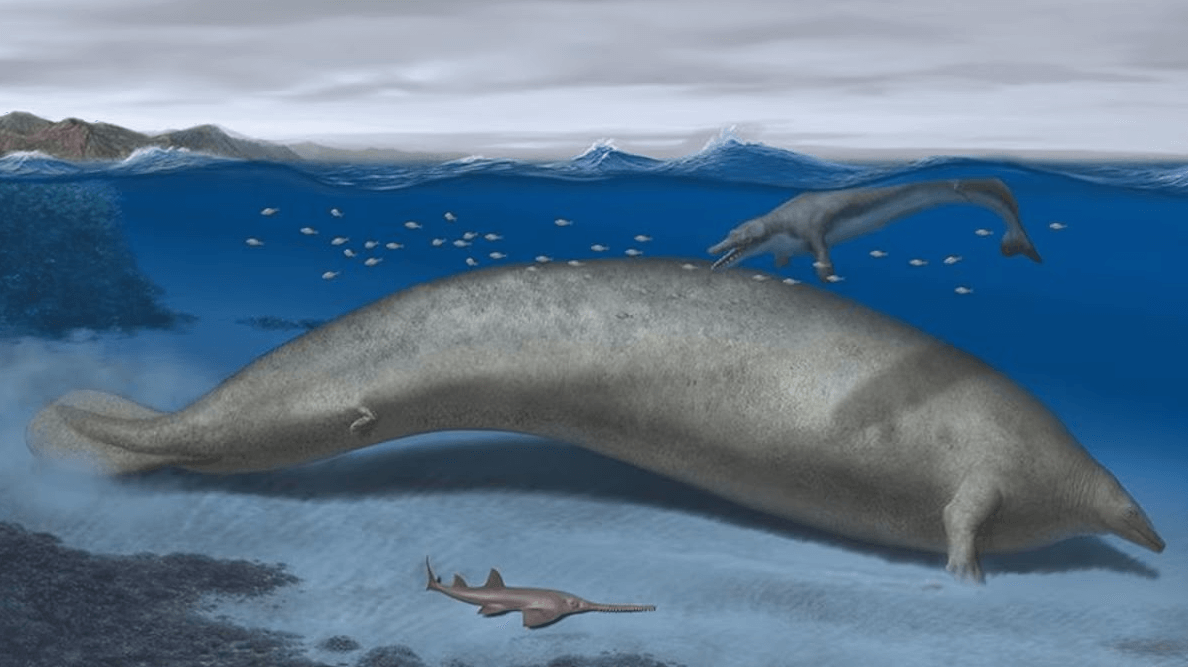

“Until now, extreme gigantism in cetaceans, like baleen whales, was thought to be a relatively recent event (around 5-10 million years ago) and associated with offshore habits. Thanks to Perucetus, we now know that gigantic body masses were reached 30 million years earlier than previously assumed, and in a coastal environment. The discovery of the new fossil shows us that the coastal environment can sustain such a gigantic animal, which was completely unexpected. In general, this demonstrates that extreme gigantism can be achieved through a completely different evolutionary path than was previously known,” Eli Amson from the Natural History Museum in Stuttgart and lead author of this 2023 study said ZME Science in a previous interview.

But not everyone was convinced. When researchers at the University of California, Davis and the Smithsonian Institution first saw these specifications, they noticed that they seemed much too exaggerated. So, the researchers took a closer look. Their formal analysis, detailed in a new study, confirmed their suspicions.

They found that the initial estimates for P. colossus didn't make sense as this type of animal couldn’t possibly exist in a marine habitat. Instead, their own estimates put Perucetus in a weight range comparable to modern whales, notably smaller than the largest blue whales on record.

Not as huge as previously thought

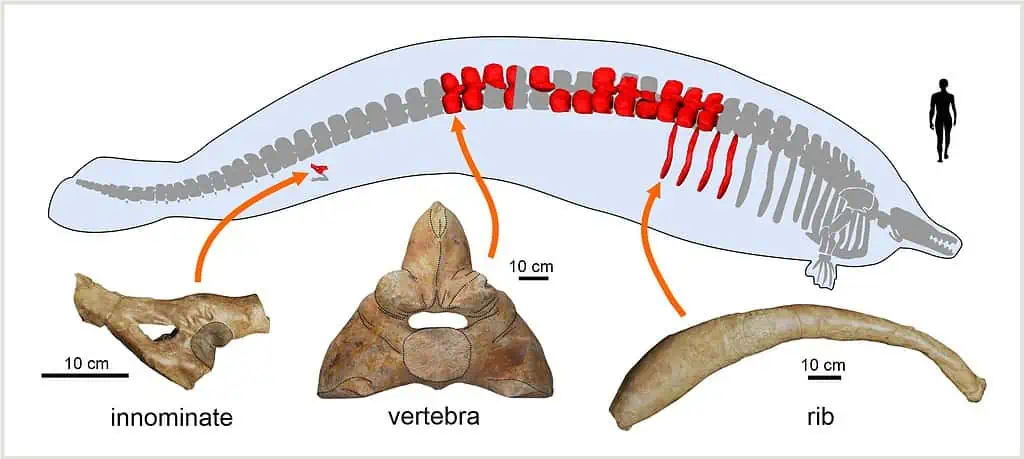

Perucetus was discovered in Peru and identified as a member of the extinct basilosaurid group of early whales, living approximately 39 million years ago. It took paleontologists over ten years to unearth its giant fossils, including 13 vertebrae, four ribs, and a hip bone. One of the vertebrae weighed a staggering 100 kilograms (220 pounds). The ribs measured 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) across.

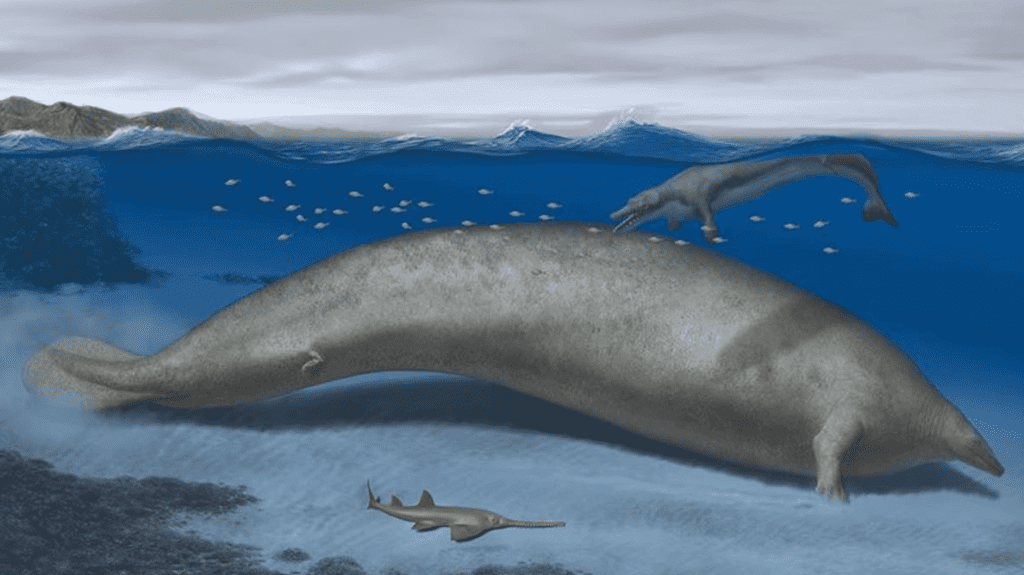

This was a massive creature, no doubt, but its initial weight estimate raised many questions. Unlike the typical mammal bone structure, which is solid on the outside with a spongy or hollow center, Perucetus‘s bones were found to be unusually dense, filled in with solid bone throughout. Furthermore, Perucetus bones had extra growth on the outside due to a condition known as pachyostosis that made the bones even denser. While this is not entirely unheard of, some modern aquatic mammals like manatees also have dense bones, which help counteract buoyancy from all the fat and blubber. This allows these animals to maintain neutral buoyancy or walk on riverbeds, as is the case with hippos.

However, when the researchers of the 2023 study calculated the skeleton’s weight in relation to the overall body weight, they arrived at an impossible animal.

“The whale would have had difficulty staying at the surface, or even leaving the sea floor — it would have needed to continuously swim against gravity to move in the water,” said Professor Ryosuke Motani, a paleobiologist at the UC Davis Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and lead author of the new study.

A newer, lower estimation

Motani and Nick Pyenson at the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of Natural History reevaluated the data on Perecetus with a fresh perspective. They discovered that many assumptions in the original paper were flawed. The main problem was using only a few bones to approximate the skeleton's weight, and then extrapolating the entire animal's weight based on the assumption that skeletal and non-skeletal mass would scale at the same ratio. However, this is not reliable, as seen in measurements of other modern animals.

Another incorrect assumption led to an overestimation of how much the ancient marine mammal’s body mass increased due to pachyostosis. Manatees, for example, are very light in comparison to their dense bones. If a paleontologist were to examine manatee fossils millions of years from now, they too would have significantly overestimated its body size using this method.

Instead, the new estimation places the 17-meter-long Perucetus between 60 to 70 tons — much lower than a blue whale. This is more in line with modern sperm whales. A 20-meter-long Perucetus could weigh over 110 tons, but would still be well below the largest blue whales at 270 tons.

“The new weight allows the whale to surface and stay there while breathing and recovering from a dive, similar to most whales,” Motani said.

But the authors who revealed the news about Perucetus colossus still support their initial assessment. Speaking to Live Science, Eli Amson, a paleontologist and curator of fossil mammals at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History in Germany and one of the authors of the original study, said:

“We are estimating the body mass of an extinct animal known from a very incomplete skeleton, so of course there's plenty of room for using different methods.”

“When you look at the blue whale, it's enormous, obviously, but it has a very streamlined shape,” he said. “If you compare other marine mammals like manatees and dugongs, they have a much rounder body shape.”

Finding more fossils could help resolve this debate. Scientists have not yet found a skull or even teeth, making it difficult to determine its diet, although the 2023 study suggests it may have fed on shellfish, coastal fish, or scavenged carcasses.

The new findings were published in the journal PeerJ.