This article was initially showcased on Hakai Magazine, an internet publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Find more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

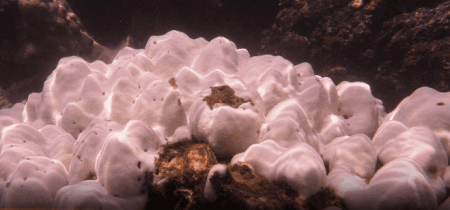

In the summer of 2020, Jennifer Pytka spent three and a half hours a day searching the internet for proof of the illegal animal trade. She would enter กระเบนท้องน้ำ, a word in Thai that roughly means stingray, on Google, and her search would quickly show images of rings, each decorated with an intricate white thorn about the size of a thumbnail. Pytka, a Ph.D. student at the Università di Padova in Italy, is looking into the previously unrecorded business of bowmouth guitarfish—a critically endangered type of ray with these thorns on their spine and brows. In Thailand, these thorns are turned into charms, like rings and bracelets, believed to have protective powers. In a 2023 study, Pytka mentions how she identified 977 of these items on online selling platforms, like Facebook Marketplace, eBay, and the Alibaba-owned e-commerce site Lazada, over 21 days. Bowmouth guitarfish amulets are just one instance of the countless protected animal products being sold online, where a global illicit market of dishonest sellers peddle their animal goods, and anyone with internet access can locate products from rhino horns to exotic orchids to tiger claws with just a few clicks. With lenient regulations, even weaker enforcement, and a lack of legal responsibility, not only is the illegal animal trade able to grow on the internet, but algorithms actually magnify sales, boosting the profits of the platforms.Products obtained from protected species can be found across all sorts of selling platforms, but with three billion active monthly users, Facebook is the leading player. Pytka found 30 percent of the bowmouth guitarfish products on Facebook and 65 percent spread across other e‑commerce sites, like Shopee and Lazada. “I’ve come to believe that Facebook is a driver of the global extinction crisis,” says Gretchen Peters, director of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online (ACCO), a nonprofit whistle-blower organization. studyBefore the internet and online trading became prevalent, sellers of animal products mainly had to reach their customers through personal connections, says David Roberts, a conservation scientist at the University of Kent in England who studies the illegal animal trade. But in the early 2000s, an increasing number of transactions in the physical world moved to the digital realm, with the illegal animal trade being no exception. Today, almost 6,000 species of plants and animals are traded illegally, and the trade is valued at up to US $23-billion annually. It is the fourth-largest illicit market, and many animals, like rhinos, pangolins, and some species of parrots and sharks, are in danger of extinction due to their popularity on the black market.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) recognizes at-risk species and establishes protections and trade bans. However, enforcing CITES rules on the ground is a different challenge.

Glenn Sant, a senior adviser on fisheries trade for TRAFFIC, a nonprofit aiming to decrease illegal trafficking, gives an example of what might happen when someone catches a protected species of shark. “The fins will potentially go to Hong Kong or China, and the meat might go to Europe,” he says, adding that the skin might become leather and the oils sold for cosmetic products. Sant says that processing, shipping, and distribution around the world can make it very difficult to trace and therefore prosecute illegal animal harvesting. That’s part of the reason Pytka chose to study bowmouth guitarfish—their unique thorns are easy to distinguish.

eBay was the first to recognize the growing issue of online trafficking and prohibited all ivory sales on its platform in 2009. Another milestone was achieved in 2018 with the formation of the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online. This partnership, led by animal welfare groups TRAFFIC, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and the International Fund for Animal Welfare, advises technology platforms on how to identify and prevent wildlife trafficking. So far, 47 companies have joined the coalition, including Meta—the parent company of Facebook and Instagram—eBay, TikTok, and other international giants like Alibaba. The coalition’s most recent report, from 2021, found that between all the platforms, more than 11.6 million products made from prohibited wildlife have been removed or banned. A spokesperson from eBay said that over 350,000 listings for prohibited wildlife items were blocked or removed in 2022. Giavanna Grein, a wildlife specialist at WWF, encourages platforms to be more transparent with the public and admits that the efforts undertaken by the coalition are just one small part of the picture. “We fully acknowledge this is a very complex and challenging issue, and there’s no one organization or effort that can tackle this,” she says.

Even with all the efforts, there are still loopholes.

Despite eBay’s ivory ban, for example, a quick search by Roberts identified what he believes to be elephant ivory being sold under a code name. The product is still so readily available, in fact, that he focuses his students’ projects on it. Similarly, a quick search on Facebook Marketplace for rhino horns for sale in southeast Asia immediately yields several posts.

Meta’s own policy prohibits “attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift, or solicit endangered species or their parts,” and in a statement, a spokesperson said that content that violates their policies is removed. However, whistle-blower reports published since Facebook joined the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online have been scathing. “Facebook policy and public comments about countering illicit content are rendered virtually meaningless by the firm’s ineffective follow-up and enforcement,” reads a

from the ACCO. To evaluate the seriousness of wildlife trafficking on Facebook, the report used search terms such as “exotic + animal + for sale” in English, Arabic, Vietnamese, and Indonesian, discovering 473 Facebook pages and 281 groups openly selling wildlife products. Over half the pages were created since Facebook joined the coalition, indicating that online trafficking seems to have increased.. Researchers found many illegal items on Facebook because their algorithm suggests similar products, connecting sellers and potential buyers. The ACCO report discovered 29 percent of wildlife trafficking pages through Facebook’s “Related Pages” feature.

a similar investigation 2020 report Avaaz, a nonprofit that supports global activism, also found that Facebook’s algorithm directed researchers to dozens of wildlife groups, over half of which contained potentially harmful wildlife trafficking content. The report suggests that Facebook’s algorithms should hide these posts instead of promoting them.

Meta is passively making money from illegal activity on its platform through embedded advertisements and transaction fees from sales, including those of trafficked animals. Peters believes that Facebook is not ready to invest in cleaning up their platform to address the issue of wildlife trafficking. She also claims that Facebook could collaborate more with law enforcement to dismantle criminal networks and make better use of the information they have on wildlife trafficking networks. Roberts implies that removing posts from these platforms is like a game of whack-a-mole, with new posts appearing as others are taken down. She suggests that there is a lack of effective measures to combat the issue.

Despite the efforts of animal welfare and social justice groups, illicit wildlife sales continue to thrive online due to the protection provided by section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields platforms from civil liability.

Peters argues that platforms are shielded by section 230, which considers user-generated content as free expression. She suggests implementing a duty-of-care law to require platforms to remove criminal activity, as illegal sales are not considered free speech.

“I believe [the platforms] should be responsible,” says Roberts, who compares online trafficking to a bar allowing drugs to be sold in the bathrooms. The establishment is responsible for allowing illicit activity on its premises. “How is that any different [from] a platform allowing illegal trade to take place?”

Both ACCO and Avaaz propose simple measures for Facebook to decrease online wildlife crime. For instance, when a user searches “bowmouth guitarfish amulets,” the algorithm could fail to return a search or prompt a pop-up explaining that the amulets come from a protected species. AI algorithms could also automatically identify questionable content or be employed to track trafficking activity. Pytka says it would be relatively straightforward to create such a system for bowmouth guitarfish rings because they’re so visually unique. In early 2023, eBay obtained an AI-based software that will supposedly make the marketplace safer. In the meantime, though, my Facebook Marketplace home page is filled with skeletal amulets, while researchers like Pytka can only guess about how many of the endangered fish remain in the sea.

This article was initially published in

Hakai Magazine

and is republished here with permission.

There is minimal enforcement or legal accountability. Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.