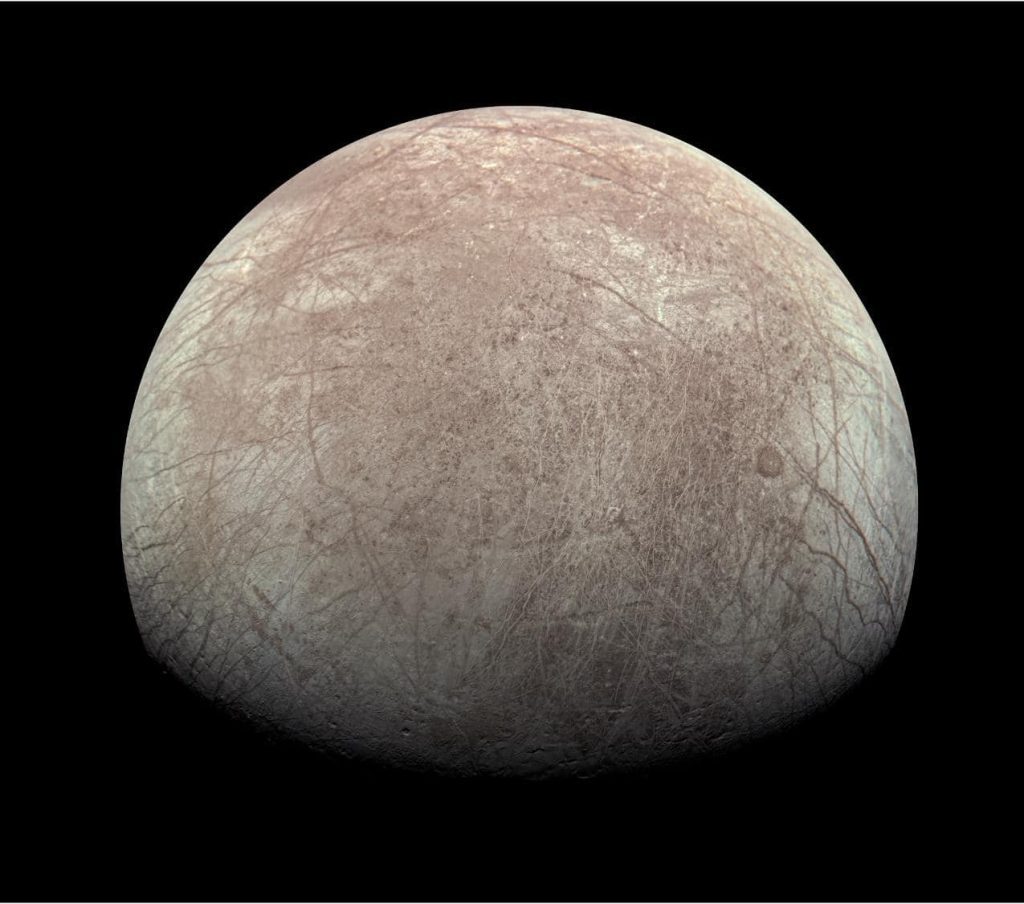

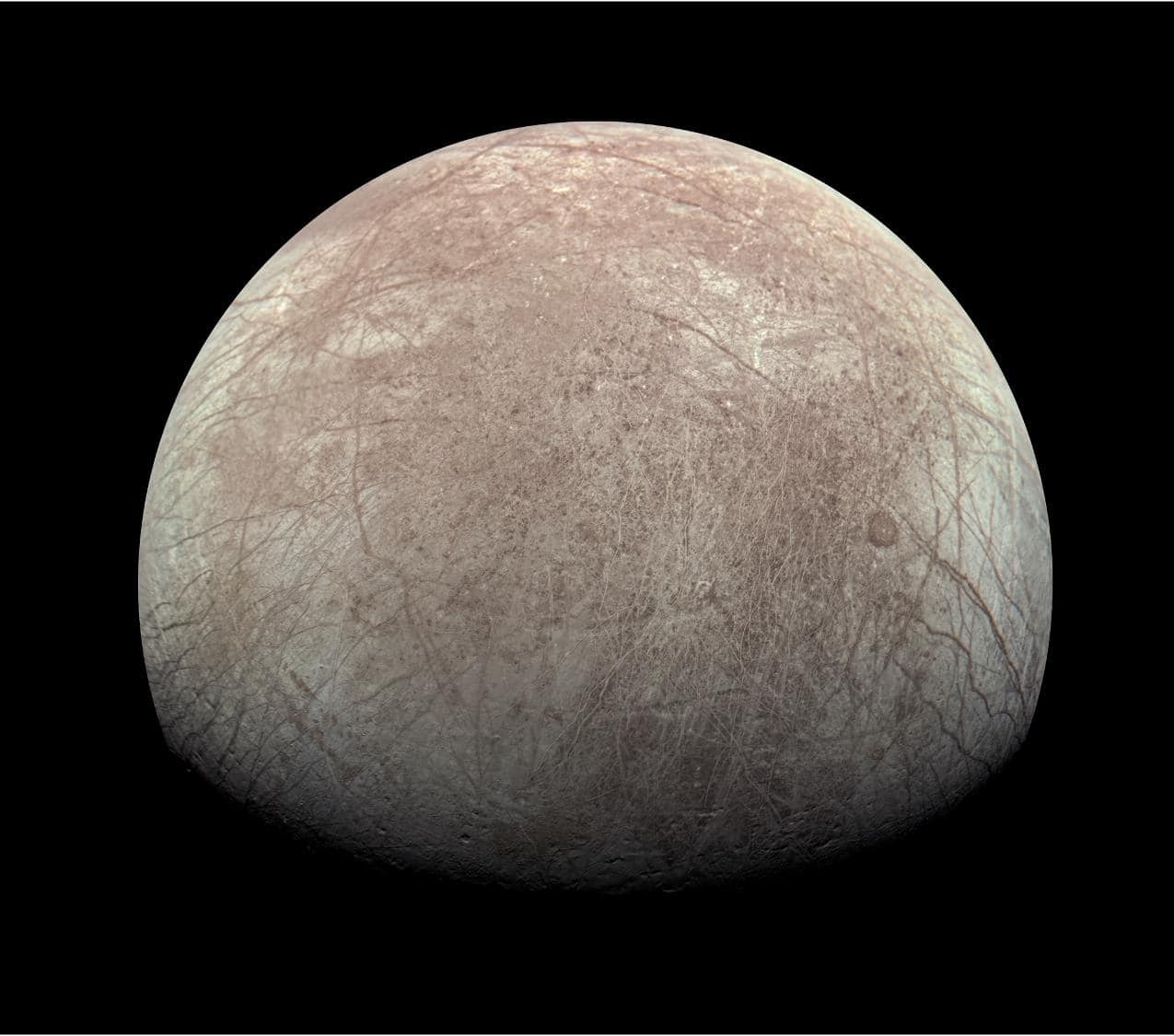

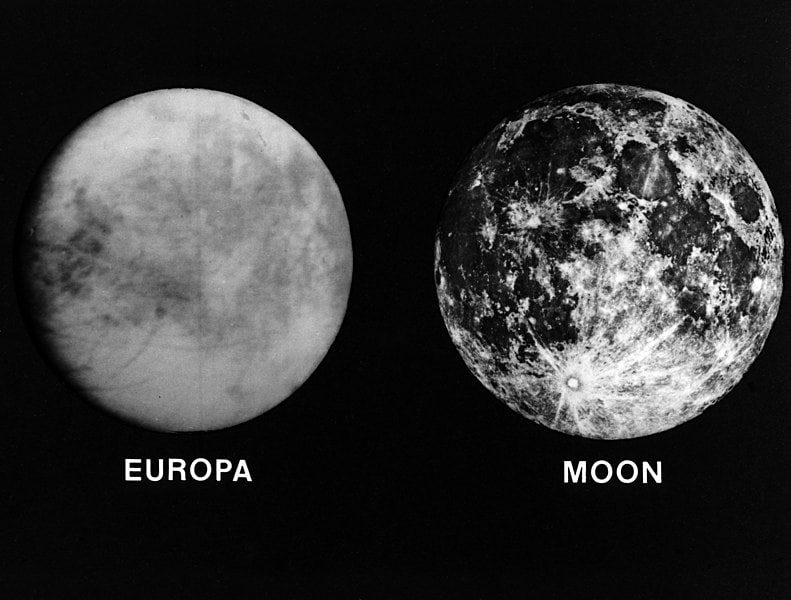

Europa stands out as one of the most intriguing celestial bodies. It’s cloaked in a 13-mile-deep (22-km) ice sheet, beneath which lies a huge ocean. Since it was discovered, scientists and the public alike have seen it as one of the best places in the solar system where extraterrestrial life may exist. Yet, recent findings from NASA’s Juno mission cast a shadow over this optimism.

Not a torrent but a trickle

The icy surface of this moon, once thought to be a robust source of oxygen, turns out to produce merely 26 pounds (12 kilograms) of oxygen per second. The findings from spacecraft Juno’s 2022 flyby contrasts with earlier computer model predictions, which estimated a much higher production rate of 2,205 pounds (1,000 kilograms) of oxygen per second.

This drastic revision of oxygen estimates on Europa has profound implications. The life-sustaining oxygen supply on Europa is less of a torrent and more of a trickle.

Perhaps all of this is not that surprising considering how oxygen is produced on Jupiter’s moon. Unlike Earth, where life-giving oxygen is a product of photosynthesis from plants and cyanobacteria, Europa’s oxygen is produced by cosmic processes. When charged particles from space bombard its icy crust, hydrogen, and oxygen molecules are released. The oxygen can then percolate through the ice and into the ocean beneath. There, it could combine with volcanic material and other chemical building blocks that may support life.

But can that work with this little oxygen? Scientists have always poetically envisioned this as Europa sort of “breathing” through its icy shell. However, the new findings show the moon seems to be choking instead.

A different sort of life

Despite this setback, hope persists. Europa is still a candidate for harboring life, albeit in a much more modest capacity than previously imagined. The scarcity of oxygen does not necessarily render Europa inhospitable for life. Rather, it reshapes our understanding of what form life might take there. You may call it coping, but if extreme life forms known to us here are any indication — whether it’s tardigrades that can survive in the vacuum of space or microbes that thrive at 121 degrees Celsius (250 degrees Fahrenheit) — life tends to find a way.

“It’s on the lower end of what we would expect,” said Jamey Szalay, a plasma physicist at Princeton University who led the study. But “it’s not totally prohibitive” for habitability.

The upcoming Europa Clipper mission, set to launch later this year, will help to clear things up. The spacecraft is expected to reach Europa by 2030, where it will explore the moon’s habitability in greater depth from above.

The findings appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy.