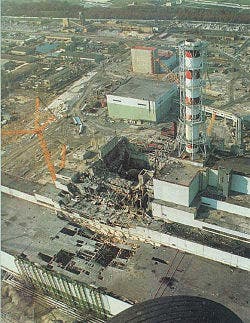

You’ve probably heard of Chornobyl, the place of the biggest nuclear accident in the world. When the disaster happened in April 1986, the area became so radioactive that everyone was forced to evacuate, leaving behind a ghost town. Even after the plant was sealed in a massive concrete dome, there was still a huge background level of radiation in the area.

While no humans live in the area, several different species of plants and animals have taken over the area, and they too are suffering major amounts of radiation. From frogs to elks, all sorts of creatures are happy that the humans are gone and they can take over the area, although they’re still suffering the effects of radiation.

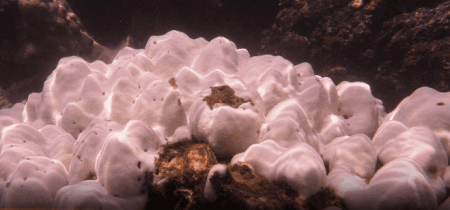

However, not everybody is suffering because of the radiation; in fact, a type of fungi (mushrooms) may even enjoy it. The fungi possess an ability beyond imagination: they can take lethal radiation and use it as a source of energy to feed and grow. Researchers have called them radiotrophic fungi.

Extreme mushrooms

For some 500 million years, fungi have been inhabiting this planet, feeding on whatever they could find, filling every biological niche they could spread to. But as resilient as they’ve proven themselves to be, who could have actually guessed that they could feed on nuclear radiation?

Researchers have suspected that some organisms (called “extremophiles” due to their “love” of extreme conditions) can thrive on radiation, but withstanding (and thriving) on one of the most radioactive places on the planet is an outstanding feat.

Researchers from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (AEC) had a hunch that the mushroom could have adapted to Chornobyl’s extreme conditions, and they investigated it by putting the mushroom to the test. They first got the idea after reading that samples brought from Chornobyl were filled with some black fungi growing on them.

“The fungal kingdom comprises more species than any other plant or animal kingdom, so finding that they’re making food in addition to breaking it down means that Earth’s energetics–in particular, the amount of radiation energy being converted to biological energy–may need to be recalculated,” says Dr. Arturo Casadevall, chair of microbiology & immunology at Einstein and senior author of the study,.

“I found that very interesting and began discussing with colleagues whether these fungi might be using the radiation emissions as an energy source,” explained Casadevall.

The key to the fungi’s ability to not only withstand, but consume the radiation for energy comes from the high amounts of melanin, which enable the fungi to both resist radiation and turn it into energy. This pigment allows the fungi to absorb the radiation and consume its energy, as opposed to being damaged by it.

To confirm this, Casadevall and his co-researchers set about performing a variety of tests using several different fungi; two types of mushrooms were used, one that had naturally contains melanin and one that was injected with the substance. They were then exposed to radiation levels 500 times bigger than the normal ones. The result? Both of them grew much faster than they would normally when exposed to radiation.

“Just as the pigment chlorophyll converts sunlight into chemical energy that allows green plants to live and grow, our research suggests that melanin can use a different portion of the electromagnetic spectrum – ionizing radiation – to benefit the fungi containing it,” said co-researcher Ekaterina Dadachova.

They took the research one step further and found that the melanin in these radiotrophic fungi is chemically identical to the melanin in our own bodies, and this led them to believe that it could be actually providing energy for skin cells.

“It’s pure speculation but not outside the realm of possibility that melanin could be providing energy to skin cells,” he says. “While it wouldn’t be enough energy to fuel a run on the beach, maybe it could help you to open an eyelid.”

As cool as it is, the mushroom may turn out to be even more interesting for space exploration. If space radiation could be turned into a reliable source of food, this could offer long-distance astronauts a source of energy supported by the interplanetary environment.

“Since ionizing radiation is prevalent in outer space, astronauts might be able to rely on fungi as an inexhaustible food source on long missions or for colonizing other planets,” says Dr. Ekaterina Dadachova, associate professor of nuclear medicine and microbiology & immunology at Einstein and lead author of the study.

Ultimately, this is a remarkable testament to the resilience and adaptability of life on Earth. The fact that even in such a dreadful environment that seems tailor-made to be anti-life, one life form has managed to turn the problem into its advantage is absolutely stunning. No doubt, we have much to learn from this fungus and the other creatures that survive around Chornobyl — and hopefully, we won’t create another environment like this one.

This article has been published more than ten years ago and has been edited.