Gulf Coast officials are warning residents to wrap up their preparations for Tropical Storm Barry. It’s almost here.

On Thursday, Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards declared a state of emergency for the region and ordered 3,000 National Guard members to be deployed for rescue and recovery operations. Friday morning, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell tweeted that high-water vehicles and boats have been pre-staged around the city in anticipation of potential rescues.

Here’s what you need to know about Barry:

What is its status is now?

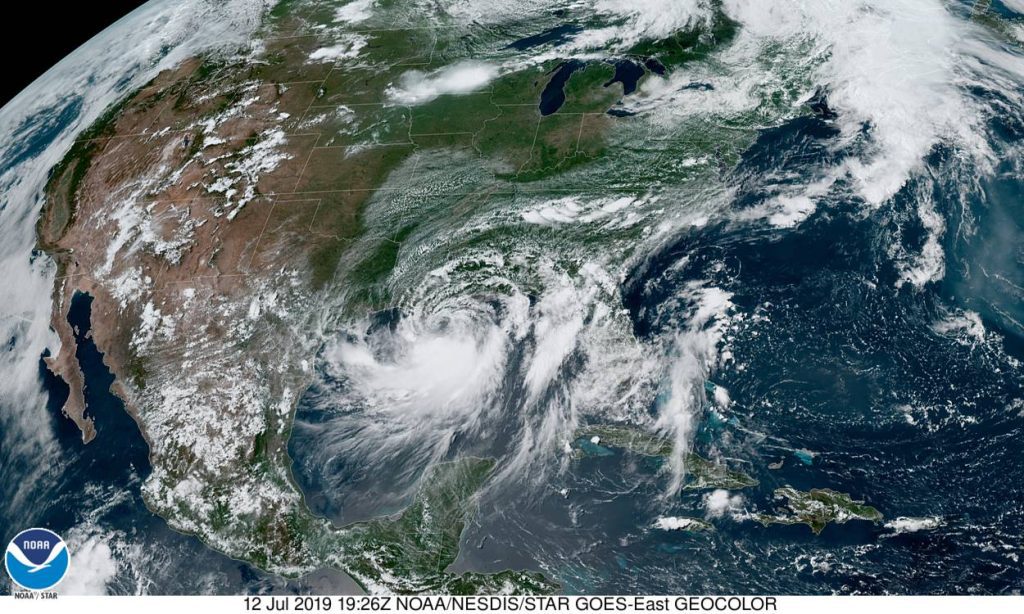

On Friday, Tropical Storm Barry moved toward the coast of Louisiana and the first bands of rain began to ripple into the region.

According to the National Weather Service’s National Hurricane Center, the storm will approach the Louisiana coast Friday night, make landfall Saturday, and move northward through the lower Mississippi Valley on Sunday.

With the storm currently about 100 miles away from the mouth of the Mississippi River, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft recorded maximum sustained winds of 65 miles per hour, according to an advisory released Friday afternoon. Tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 175 miles from the storm’s center (about the distance between New York City and Baltimore), according to the National Weather Service (NWS). The advisory also notes that an oil rig near the mouth of the Mississippi reported winds of 76 miles per hour with 87-mile-per-hour gusts of winds.

By the time it lands in Louisiana, Barry is expected to reach hurricane status, defined as tropical cyclones with winds reaching at least 74 miles per hour.

Flooding is the biggest threat

Tropical Storm Barry is predicted to make landfall by Saturday and will weaken once it hits the coast and travels inland.

Its biggest threat is water, not wind, according to the NWS’s New Orleans outpost, with significant flooding expected across the north-central Gulf coast.

Barry’s slow crawl means a steady drench for the region (for the past day or so, the storm has crept along at the well-below average pace of just 5 miles per hour). Steadily rising waters near shorelines could swell up to 5 or 6 feet in some areas if peak storm surges sync up with high tide, according to the NWS. The water level in the Mississippi River is already at an abnormally high level. Recent flooding has raised the level to 16 feet rather than its normal 6 to 8 feet for this time of year.

The NWS predicts between 10 and 20 inches of rain or more—with the heaviest downpour between Friday and Saturday nights—that could lead to life-threatening flash flooding and the river inundation. In the rest of the Lower Mississippi Valley, total rain estimates are lower: an expected 4 to 8 inches, with isolated maximum amounts of a foot. A couple of tornadoes across southeast Louisiana, southern Mississippi, and along the Alabama coast are also possible on Friday, the government agency says.

The National Weather Service is warning residents to plan for a weekend of severe weather by stockpiling a few days’ worth of non-perishable food and water—as well as preparing for power outages by charging mobile devices, sharing location with loved ones ahead of time and locating flashlights and weather radios. The weather agency has also instructed residents not to drive or walk into flooded areas, and to seek higher ground when necessary and possible.

The agency has also suggested neighboring areas from upper Texas to the Florida panhandle should monitor the storm’s movement.

Is this normal?

We are officially in hurricane season, which began June 1 and will last through the end of November.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 97 percent of storms in the Atlantic occur during hurricane season, which sees an average 12 named storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes. For the Atlantic, the season peaks in September.

The formation of Subtropical Storm Andrea in May kicked off 2019’s hurricane season early, marking a fifth year in a row that a named storm has formed before the official June 1 startline.

Scientists have long expected climate change would lead to longer and more intense hurricane systems, as evidenced by the devastation wrought by tropical storms in recent years. Last year’s hurricane season saw 15 named storms, including eight hurricanes; taken together, Florence and Michael, which struck the southeast in 2018, killed 102 people and cost $49 billion in damage. The previous year, Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, Irma struck the U.S. Virgin Islands and Florida, and Harvey caused historic flooding in Texas.

“These are things we expected to happen, and now we’re seeing these things happen,” Stephen Strader, an assistant professor of geography and the environment at Villanova University, told Popular Science earlier this year.