The first time I encountered poppers, I watched a nun do them. I was in fifth grade.

It was the final scene of Act 1 of “Nunsense,” a riotous Off-Broadway musical detailing the fundraising antics of an ill-fated but endearing group of convent sisters. One nun had found a suspicious-looking bag in a high school bathroom and presented it to Mother Superior Mary Regina. Once alone, Reverend Mother rummaged around in the bag and pulled out a small, brightly-colored glass bottle. She gave it the once-over, quizzically reading its name aloud: “Rush.”

Unscrewing the bottle, Mary Regina immediately revulsed at the harsh chemical smell contained within, but not before taking an unintentional whiff of the potent fumes. Soon the straight-edge sister experienced a sensual head rush of biblical proportions. The rest of the nuns found her writhing on the floor, higher than a church steeple, moaning and shouting, “FREE WILLY! FREE WILLY!”

As a 10 year-old audience member, I found the Reverend Mother’s silliness amusing, but it would be another decade before I fully understood what had transpired on that stage—when I came across a neon yellow bottle of Rush myself. Only, this one was about as far as you could get from a convent.

There are countless brands of similar-sized bottles just like RUSH. Others have names like “Jungle Juice,” “Quicksilver,” “Ram,” and “Blue Boy.” All give off a heavy industrial stench and bear a similar chemical footprint. And though they may be labeled for uses like “video head cleaner” or “room odorizer,” you mainly find them in sex shops. It’s safe to say nobody’s buying them for home improvement purposes.

“Poppers” is the common name for this suite of compounds called alkyl nitrites. Though they may seem like the latest solvent for rebellious teenagers to huff, they’ve been around for decades. And they represent much more than a drug fad—they’re a cultural phenomenon whose journey has helped shape queer life as we know it.

Men who were part of the gay nightlife scene in the 70s, 80s, and 90s say you could walk into a club and immediately smell poppers. The scent was a backdrop for the triumphs and trials of queer men in the latter half of the 20th century. Now, it conjures collective memories of the gay bars of yesteryear: tight pants, dark spaces, and speakers blaring Donna Summer and The Village People.

The Stonewall uprising of 1969 set a cautiously optimistic tone for the 70s, one that suggested to queer people that their rights to be with each other unapologetically were on the horizon. Following the broader sexual liberation movement of the decade, more queer men became eager to explore themselves as sexual beings. And decreased police raids on gay bars, clubs, and discos (like the one that triggered Stonewall) popularized spaces allowing that exploration.But that didn’t come without baggage. For many, using drugs in these clubs was a way to combat the still-pervasive stigma of not being straight.

David Wohlsifer, a psychotherapist and sex therapist, says drugs and sex are often inextricably linked. Drugs reduce sexual inhibitions, which are often caused by feelings of shame, trauma, or body dysmorphia. He says queer men especially deal with a lot of shame related to their identities both in and out of the bedroom. Fifty years ago, when society was even less accepting of homosexuality than it is today, that shame could feel overwhelming.

“You walk into this club hating yourself for who you are, hating yourself for what you want to do. And then there’s this magic pill that makes you, for a few minutes, feel euphoric; it makes you feel self-worth instead of shame,” Wohlsifer says. “People go for it.”

Enter poppers: They aren’t a pill, but they certainly make you feel euphoric. A few seconds after inhaling deeply from the amber glass bottle, you can feel your face warming as blood rushes to your head—and everywhere else in your body. A minute or two later, the sensation subsides, and you can do it all over again. In “The Poop on Poppers,” which appeared in a 1977 issue of the Bay Area Reporter, a queer weekly publication, Louis Parrish writes, “Fans claim that poppers serve the dual purpose of putting them more out of it and at the same time putting them more into it.”

It’s a kind of high that makes you feel open mentally, physically, and, for queer men in particular, sexually. In a 1982 study of poppers and their use, psychiatrist Thomas Lowry called them “the nearest thing to a true aphrodisiac.”

Of course, alkyl nitrites are far from a Greek myth: Their immediate physiological effects are well-documented. When inhaled, they quickly relax involuntary smooth muscle. They also act as vasodilators that widen blood vessels, lowering blood pressure and increasing blood flow throughout the body. That surge of blood means extra oxygen and causes a head rush which, along with the release in muscle tension, leads to the giddy high Mother Superior Mary Regina so elegantly depicted.

Poppers have added physical benefits for penetrative sex: The human reproductive tract is built by smooth muscle, and the anal sphincter, while voluntarily controlled, is surrounded by smooth muscle that can make penetration easier when it’s relaxed. For many men who have sex with men, poppers have obvious practical applications. It’s no surprise they’ve gained a reputation akin to sex in a bottle.

But the story of poppers started long before gay bars and glass bottles—when French chemist Antoine Balard first synthesized amyl nitrite in 1844. Even then, Balard noted that smelling the chemical’s vapor made him lightheaded, which we now know is a consequence of your blood pressure dropping. Fifteen years later, British chemist Frederick Guthrie described other physical effects: throbbing arteries, flushing of the face, and increased heart rate.

British physiologist Benjamin Ward Richardson believed no other known substance at the time produced such a profound effect on the heart, and even passed around samples of amyl nitrite at a medical conference so his audience could try it for themselves. In 1864, he was the first to theorize that the chemical caused vasodilation.

Three years later, Scottish physician Sir Thomas Lauder Brunton brought together all prior research on amyl nitrite and outlined the compound’s medical applications. At the start of his career as a physician, while making his rounds at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary on a cold December night, he noticed a patient whose bouts of angina pectoris were concerningly severe, frequent, and long-lasting. One of the most common symptoms of cardiac disease, angina pectoris is chest pain that occurs when the heart muscle is starved of blood. From bloodletting to brandy, agents typically used to ease that anguish weren’t helping. Exhausted of all options, and suspecting that an overly-tense artery caused the angina, Brunton put several drops of amyl nitrite onto a cloth and had the patient inhale it.

“My hopes were completely fulfilled,” he wrote in British medical journal The Lancet. Within a minute, the patient’s face flushed and the pain completely disappeared. Over the next several decades, physicians around the world caught wind of Brunton’s discovery but hesitated to make amyl nitrate a standard treatment, perhaps because of its signature rush. In 1881, an editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal called amyl nitrite “a neglected drug,” scolding doctors for not using it to relieve clearly suffering patients.

Physicians eventually caught on, and amyl nitrite became one of several vasodilators used to treat angina pectoris. By the early 20th century patients were receiving tin boxes containing glass ampules of the chemical wrapped in cloth, like pieces of saltwater taffy. During angina spells, they’d crush the capsules, allowing the amyl nitrite to soak through the cloth to be inhaled. The sound of the breaking glass gave this drug the name “poppers.”

Doctors used poppers as a standard treatment for angina for decades before replacing them with modern vasodilators like nitroglycerin, but how they transitioned to the clubs of The Castro and Greenwich Village is still somewhat of a mystery. In Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics, Richard Davenport-Hines assumes patients prescribed amyl nitrite must have noticed some pleasant effects happening outside their chests.

“It was surely as early as the 1870s that amyl nitrite users discovered that the rush of blood caused by inhaling increased the sexual excitement of men,” Davenport-Hines writes.

Toby Lea, a social scientist at the German Institute for Addiction and Prevention Research who studies the intersection of substance use and queer communties, says it’s plausible that people presecribed poppers quickly caught on to their other uses.

“With any drug that starts as a prescription medication, if it does have any kind of psychoactive effects, people discover it pretty quickly,” Lea says. “And a lot of drugs have their genesis in the gay scene before bleeding out to other cultures.”

In 1960, after nearly a hundred years of documented medical use of amyl nitrite with no associated fatalities, the FDA approved poppers as an over-the-counter drug. But shortly after reports of high recreational use, they reinstated the prescription requirement. By the time of Stonewall at the end of the decade, the first commercial brand of poppers, “Locker Room,” was on sale in Los Angeles. It was a different form of alkyl nitrite (with similar effects) called isobutyl nitrite, a way to get around the prescription requirement. Soon, practically everyone in the club scene had gotten a whiff.

Denton Callander is deputy director of New York University’s Spatial Epidemiology Lab, and much of his research focuses on sex and queer communities. He thinks the disco scene was a key element in the journey of poppers from the medicine cabinet to the nightstand.

“Disco is many people, not just gay men,” he says. A staple of mid-20th century counterculture, disco was originally where marginalized folks went for a pleasurable rebellion—they were kaleidoscopes of identity and experience. Dance floors were a nightly hotbed of interactions between people from all walks of life. Introducing poppers to this volatile, promiscuous mix created nothing short of an explosion.

While queer men weren’t the only people using poppers during the disco era, Callander says they in particular took to the amber bottles because of their practical applications for gay sex. They soon became popular in gay bathhouses, where queer men would gather to relax and engage in sexual activity.

“Even if you don’t use them or you think they’re stupid, they are in some ways part of our history, of what it means to be gay men,” Callander says.

There were deeper motivations, too, says Jason Orne, a sociologist at Drexel University. He brings up the concept of minority stress, wherein stigmatized groups experience psychological pain through harassment, discrimination, and related experiences that puts them at high risk for physical and mental health issues. “That creates situations where we drink more, we do drugs more, we have sex more,” he says. “We sort of are in these spaces that allow us to seize some forms of pleasure and take some power from that.”

Orne brings up cultural anthropologist and sex theorist Gayle Rubin’s idea of “the charmed circle,” or what society considers “good” or “moral” sex: heterosexuality, monogamy, sober sex, etc. Queer sex is placed outside that circle, along with all the other types of sex society deems “bad.” “If you’re already on the outside in one way—you’re queer—then you start to also question the rest of those issues of morality,” Orne says. “We have other forms of morality that emphasize being different.”

There’s also social bonding that results from communal spaces like dance floors. Orne calls this phenomenon “naked intimacy,” when people in sexually-charged spaces like discos feel more connected to each other, especially when having drug-fueled out-of-body experiences.

“Poppers, in a way, mimics physiologically this social experience that people have. So I think they pair together really well,” he says. These bottles helped disco-goers achieve a type of “collective effervescence,” a sociological term for when a group of people come out of themselves together. It happens during religious experiences, concerts, sporting events, and, yes, at gay bars—and Orne says it helps create bonds between complete strangers.

“People routinely talk about telling very intimate details of their lives and having very deep conversations with people they barely know, because they did drugs together or had sex in the same space,” Orne says.

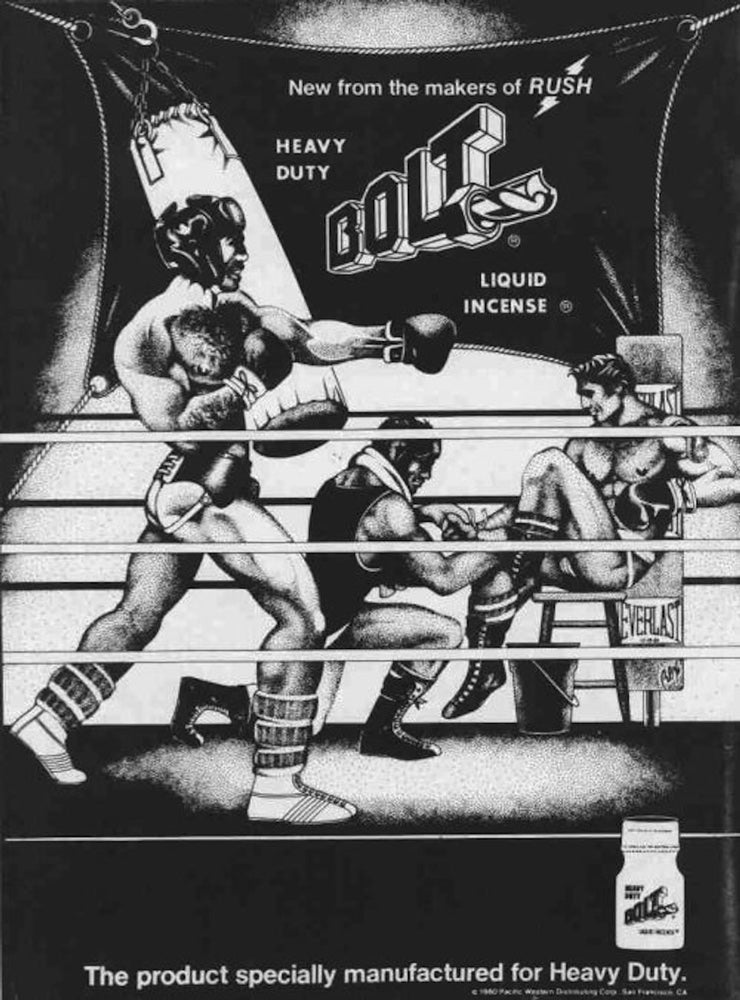

Flip through archives of LGBTQ weeklies from the 70s and 80s, and you can tell that poppers were part of queer hookup culture long before the digital age. Personal ads contained code words for sexual preferences: One of those words was “aroma,” which referred to poppers. Nearby, in the classifieds, entries advertised mail order poppers. Some publications ran full-page ads from poppers manufacturers themselves: Tom of Finland-esque drawings of buff, shirtless men riding motorcycles or swinging at each other in boxing rings told readers that all they had to do was sniff a bottle of Rush or Bolt to become Adonis.

The tide started to turn on poppers in the early 80s, when the AIDS crisis began to take hold of queer communities across the globe. Starting as early as the late 70s, rare and mysterious infections afflicted large numbers of people—mostly queer men—in cities across America. Doctors scrambled to figure out what was causing these young, previously healthy patients’ immune systems to collapse. In 1982, the CDC called the disease “acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)” for the first time, but how it spread or where it came from remained a mystery. It would take another year for scientists to identify HIV as the cause, and more than a decade to trace the virus back to its animal origins.

But during the days when AIDS was still a terrifying and fast-killing mystery without any real treatment, one potentail link stuck out: Nearly all queer men dying from the disease had used poppers at some point.

In 1985, a study linked poppers to Kaposi’s sarcoma, one of the most common infections in AIDS patients. However, the study didn’t look at the physiological pathways that would may have connected them—its results were based on correlations found within a survey of patients. About a year later, most AIDS researchers had discounted this theory.

Still, a poppers hysteria rippled throughout the U.S., and some prominent AIDS activists fervently supported a ban on alkyl nitrites. Hank Wilson and John Lauritsen co-authored “Death Rush,” a book detailing what they believed to be unequivocal evidence of the link between poppers and AIDS, and supposedly damning information about their manufacturers. In 1978, the poppers industry was worth an estimated $50 million, a figure that Wilson and Lauritsen teased may have “doubled or tripled” by the time they published in 1986. Citing “misinformation” campaigns and studies about the drugs’ safety, the authors built the case that Big Popper, as it were, was powerful and corrupt enough to fuel a deadly epidemic.

But more than 30 years after doctors first identified AIDS, there remains no convincing evidence of its link to poppers. Callander says poppers could actually reduce the risk of HIV transmission in some people: Relaxing the sphincter muscle can prevent skin from tearing during sex, lessening the likelihood of the infection spread through contact with blood (which is why HIV is so much more common in men who have sex with men in the first place).

Still, Wohlsifer points out that while the chemical signature of alkyl nitrites doesn’t lend itself to HIV transmission, poppers do decrease inhibitions during sex. “When you’ve decreased inhibitions, you’re more likely to be unsafe,” he says.

Poppers may cause a brief period of euphoric wooziness, but they affect the body differently than other volatile chemical inhalants (i.e. sniffing glue or paint). The former interact with smooth muscle, while the latter directly target the brain and nervous system. Vincent Cornelisse, a sexual health specialist at Kirketon Road Centre in Sydney, Australia, says inhalants affecting neurons are associated with brain and peripheral nerve damage, but alkyl nitrites aren’t.

Poppers may not kill your brain cells, but Cornelisse acknowledges they’re not quite the elixir of life. Rapidly altering your blood pressure can cause some uncomfortable, if mild, side effects: headache, dizziness, nausea, and a racing heart.

“They tend to be problematic mainly if you use a large amount of poppers, and they tend to not last long if you stop using poppers,” Cornelisse says. But he advises those with pre-existing medical conditions like heart disease to take care. Alkyl nitrites also have a potentially fatal interaction with erectile dysfunction medications like Viagra: Because both drugs cause vasodilation, using them together can lead to a catastrophic drop in blood pressure.

There have also been rare cases of more serious conditions associated with poppers use. Using an excessive amount at once (usually by drinking them, which is a terrible idea) can cause potentially fatal methemoglobinemia, which is when the blood’s hemoglobin fails to properly carry oxygen. Then there’s “poppers maculopathy,” referring to eye damage caused by the use of a specific type of alkyl nitrite—isopropyl nitrite—which became popular in Europe after the European Union banned the more common form of the drug.

The vaguely yellow liquid can also cause irritation and burning upon contact with skin. Regular users may exhibit what some call “poppers nose,” when scaly, irritated skin forms around the nostrils after too many close calls with the bottle’s surface. Alkyl nitrites are also highly flammable: A massive 1981 fire in San Francisco may have started at a warehouse full of poppers.

For the most part, though, the scariest claims about poppers aren’t supported by data. They’re not addictive (though users can build up a tolerance), they don’t cause AIDS, and their effects don’t last more than a minute or so. They’re not totally harmless—most things you inhale aren’t, after all—but Orne calls them a “low-commitment drug.”

That hasn’t stopped people from preaching about the dangers of poppers. “I think the reason why people think it is [killing their brain cells] is because it has that sort of chemical smell, so people equate that with something that’s not natural and dangerous,” Lea says.

It also hasn’t stopped countries from regulating them. Canada outlawed their sale in 2013, and a Volkswagen executive in Japan was arrested in 2017 with an illegal bottle of “Rush.”

In the United Kingdom, the Psychoactive Substances Act of 2016 included poppers on a list of drugs to be banned. Several months before its enactment, a proposed amendment to exempt poppers from the legislation failed, prompting conservative member of parliament Crispin Blunt to out himself as a poppers user in a speech. The government eventually stated that the ban would in fact not include poppers, citing that, unlike other psychoactive chemicals, they don’t directly affect the nervous system.

Australia’s regulatory drug agency, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, proposed rescheduling alkyl nitrites to the same category as heroin and cocaine last summer. The change was met with severe backlash from LGBTQ health professionals like Cornelisse, prompting the government to hold a community dialogue to better inform the legislation. The TGA is expected to reintroduce the revised version of the legislation this summer.

In the U.S., poppers occupy a gray legal space. State governments began banning them during the AIDS crisis, worried about their proposed link to the disease. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, a legislative staple of the War on Drugs, included language to classify alkyl nitrites as a drug unless they were produced and marketed for some purpose other than human consumption. That’s why they now have labels that say “room odorizer” or “leather cleaner.”

Through it all, Orne says governments have never been driven merely by health concerns. “Because they’re associated for a lot of people so closely with sex and gay sex in particular, I think they do have a more illicit reputation,” he says.

While poppers have been inextricably linked to queer men since they first burst onto the disco scene, they haven’t been exclusively so. When actress Lucille Ball died in 1989, an autopsy found traces of amyl nitrite in her system—though the fact that she suffered from cardiovascular disease later in life meant she was likely using them for their intended medical purpose.

In a 2012 memoir detailing her alleged racy affair with John F. Kennedy, former White House intern Mimi Alford described a scene at an L.A. party in which the young president broke a capsule of poppers and forced her to inhale. Ted Kennedy was also smitten with the aphrodisiac, according to former aide Richard E. Burke’s accounts of his former boss’s antics in “The Senator: My Ten Years With Ted Kennedy.” Burke recalled the senator’s motorcade driving past a head shop in L.A. during his 1980 presidential campaign, when Kennedy asked him if they could stop and buy some poppers. When Burke explained how bad that would look in the press, Kennedy pounded his fists against his thighs like a petulant child, singing, “I want poppers! I want poppers!”

The Kennedys weren’t the only straight people who enjoyed a good sniff of alkyl nitrite. A 1977 front page of the Wall Street Journal contained an extensive story about poppers and their use, and quoted an L.A. businesswoman with a penchant for the substance.

“I could really use a popper now,” she said.

Today, young straight folks are catching onto the alkyl nitrite craze. It may be because people, regardless of sexual orientation, are having more anal sex than ever before, or perhaps because relaxing smooth muscles can make vaginal and oral sex easier, too. Or it could be because they provide a fun, low-commitment high at clubs and parties, which may have increased appeal in an age of widespread awareness of other drugs’ dangers.

Alkyl nitrites weren’t borne out of a miraculous moment of queer alchemy, but it was queer people who made poppers into what they are today. “Straight people doing the same thing just doesn’t have that same cultural connection,” Orne says. In turn, the chemical compound helped us explore our sexualities and form communities, working toward a future where we’d be less afraid to seek pleasure. Queer liberation has always centered around the radical decision to exist outside restrictive norms that deny us that. Bricks, marches, and Supreme Court decisions have been invaluable in the fight, but you can’t ignore the power of a little glass bottle.