Hear more about author James Vlahos’s experience in the Army’s new smell simulator on the PopSci Podcast.

I´m Army, Special Operations. My mission: to sneak up on a rebel training camp. If the intelligence is right-if the place is being operated by the enemy Tiger Brigade-then I´m supposed to plant a radio transmitter so that F-16 pilots can launch smart bombs directly to the target. I just need to make absolutely sure that the location is correct-that the rebels are indeed based here. And that won´t be easy.

I creep through a dark drainage culvert, my helmet skimming the ceiling. There´s graffiti on the walls, puddles and trash on the ground. The place smells like damp earth and moldy concrete, a bit like my parents´ cellar- although home didn´t have bats overhead or rats underfoot. I emerge in a forest, by a river, at night. The air is crisp and piney. After the dank culvert, the change is so refreshing that I initially don´t notice the cinderblock building on the hilltop ahead. I don´t notice the sentry on the roof, standing at a machine gun and looking right at me.

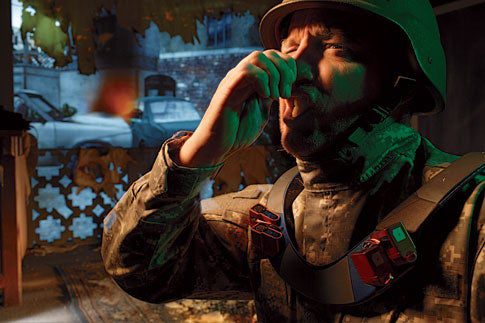

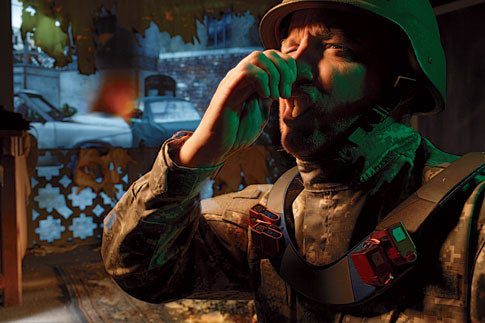

Good thing I´m not actually a soldier in a war zone. I´m in Los Angeles, standing in cubicle-land on the third floor of a modern office building. On my head are virtual-reality (VR) goggles with a stereoscopic, 90-degree field of view of the forest. In my hands is a PlayStation-type controller for directing my movements. And around my neck is an oval of blue plastic fitted with four vented metal modules the size of Zippo lighters. Wirelessly controlled by a nearby stack of computers, the modules transform what would otherwise be standard-issue military VR-for along with sight and sound, this training exercise features the smell of war.

The idea of using odor to help train soldiers may seem asinine, or ingenious, or maybe both. That´s par for the course at the oddball outfit where the project was born, the Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), a joint operation of the University of Southern California, Hollywood, theme-park designers and the U.S. military. If anyone can find a way to use smell to make VR feel more real-an idea that´s simple in principle but complicated in practice-it´s probably the people here.

At the ICT, movie directors, television writers and videogame makers work in consultation with captains, colonels and generals in an office created by the lead set designer for Star Trek. The entertainment-industry folk get Department of Defense dollars-$145 million has been committed to the ICT since its inception in 1999-to research technology years from commercialization. And the military gains the savvy of an industry that knows how to engage Generation Xbox, whose members must be recruited and trained in large numbers for operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and beyond.

To understand why the military would experiment with smell-enhanced simulation, consider how war itself has changed. Traditional combat is akin to chess, with high-level commanders directing troops and equipment around the battlefield and individual soldiers typically functioning as order-following pawns. Contemporary combat, however, is more often characterized by small-unit operations in urban terrain. Key tactical decisions are often made at the bottom of the chain of command rat

The military has long had sophisticated war games for big-picture, Cold War”era strategizing; it possesses

excellent simulators, accurate to the last button and dial, for practicing skills like driving a tank or flying a plane. Teaching ground-level decision-making under stress, however, is relatively uncharted territory, and that´s where the ICT comes in. For the new generation of simulators, the idea is to create virtual environments where trainees can practice tasks such as distinguishing hostile combatants from innocent civilians and calling for fire. The goal isn´t to teach specifics like how to aim a gun, but rather for trainees to practice making choices in an environment that both looks and feels like real war.

Olfaction could be key. A number of researchers believe that smell, more than any other sense, can powerfully and immediately trigger emotions, memories and states of arousal-all of which, when manipulated adeptly, can boost the sense of immersion and thus the quality of training in VR. In short, smellier simulators could produce smarter soldiers. “We started out thinking that the human was a visual animal only,” says Roger Smith, chief scientist for the Army office charged with procuring new simulation technology. Sophisticated sound systems followed, and now the military is intrigued by the prospect of tapping the power of smell. “Olfaction is the next step,” Smith says.

The prototype simulation I´m blundering through is called DarkCon; the aroma-emitting device is known as the Scent Collar. Both were the vision of ICT researcher Jacki Morie, revered out-of-the-box thinker and resident crazy aunt. Morie, 56, is a computer artist whose work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; a VR pioneer, she´s been engineering artificial worlds since the late 1980s. Favoring folksy prints and craft-fair jewelry, Morie wouldn´t attract a second glance at the Sunday farmers´ market-you´d never peg her as a military insider. Her expertise with computer graphics and simulation, though, have gotten her work not only with Hollywood visual-effects houses, but also with the Army, Navy and other Pentagon entities. In the mid-1990s, Morie was one of two authors of a proposal that led to the creation of the ICT.

Many of the immersive VR technologies developed at the ICT have been used to instruct thousands of Army recruits at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. “Everybody who has been to the Middle East says two things about the simulator” at Fort Sill, says George Durham, who oversees its operation. “One, that it´s really good and realistic. Two, that it´s entirely too clean and there´s no odor with it.”

by John B. Carnett

Morie watches as I continue my DarkCon demo, charging through open terrain under the sentry´s watchful eye. “He´s not a very good forward observer,” she says to a colleague. I reach the building and try to figure out where I´m supposed to drop the radio transmitter. Unfortunately, I never get the chance. The sentry doesn´t fire his machine gun, but he does alert another rebel, who releases a Doberman pinscher. The beast is charging at me now, fangs bared,

saliva trailing. The last thing I smell before the screen goes black is the hot, wet scent of dog breath.

This, then, is the brave new world of olfactory VR-and it looks a lot like 1962. That´s when Hollywood unveiled Sensorama, an immersive, 3-D arcade-game prototype in which participants rode a motorcycle through the streets of New York while fans spread around Big Apple aromas such as the smell of pizza. The sunset of Eisenhower was in fact the heyday of scented media, with the release of the 1959 film Behind the Great Wall in AromaRama, and 1960´s Scent of Mystery in Smell-O-Vision. Both bombed. “A beautiful old pine grove in Peking . . . smells rather like a subway restroom on disinfectant day,” Time magazine wrote of Behind the Great Wall. The filmmakers were stymied by technological challenges-securing believable scents, dispersing them at the right times, and changing odors without overlap-that today´s military is working to solve.

In war, bombs explode, trucks burn, and sewage sloshes through the street. Veterans can´t forget the odors, and newly deployed soldiers are often so overwhelmed by the olfactory assault that it distracts them from the tasks at hand. To prepare troops, the Army and Marines use simulations that expose soldiers to noxious odors-melting plastic, rotting flesh-before deployment to Iraq, where the smells may be encountered for real. Smell is also being used to teach trainees to recognize specific dangers. The odor of burning wires in a flight simulator, for example, tells you that you have an electrical problem and had better land; the smell of cigarette smoke in a VR scouting scenario is a warning that an empty building might be occupied by the enemy.

For the scents themselves, the military turns to the multibillion-dollar flavor and fragrance industry, the companies that make Chanel smell sexy, Big Macs savory and Joy lemon-fresh. Although you won´t find it mentioned in their glossy annual reports, some of these scent houses also know how to synthesize battle-appropriate aromas, and Morie procured samples from several companies for DarkCon. Curious about the art and science of scent manufacturing, I arranged a visit to one of her primary suppliers before going to the ICT. I even had a mission from Morie: to secure new odors for the culvert and forest in DarkCon.

The warehouse headquarters of Intercontinental Fragrances are located in the sprawling outskirts of Houston. Just inside the front door, a visitor´s nose is bombarded by an aroma best described as burntcoffeewatermeloncottoncandyspice. Marna Arlien, a marketing representative, apologizes when she comes up to the reception area. “By the time you leave tonight, your clothes, your shoes, everything will smell like this place.”

Arlien leads me to the scent library, a large room lined with giant blue flat-file cabinets. She pulls a drawer open to reveal hundreds of little brown bottles, grabs one, and opens it. After dipping a thin cardboard strip into the liquid, she passes it to me. I hold the strip to my nose and inhale. Pretty good for the forest, but perhaps too fruity. The next strip is better. I make it through five more before my head begins to spin. “Don´t worry, they´re all safe,” Arlien says. “I´ve had three kids while I was working here, and none of them have eight eyeballs, 10 arms or anything.”

Finding realistic smells is difficult, Morie had warned me. She was right. There are a few hits-three options for the forest and an excellent “Wet Dirt” for the culvert-but many more misses. One reason for this is commercial, Arlien explains. The scent industry, for obvious economic reasons, is oriented toward making things smell good, not bad or even true to life. Another reason, however, is scientific. Creating realistic smells is complicated because smell itself is complicated, exceedingly so.

The human nose can perceive at least 10,000 distinct odors, and possibly 100,000 or more. We can smell odorants in the air at a level of a few parts per billion. The Nobel Prize for figuring out exactly how we hear was awarded in 1961; for vision, in 1967. But the Nobel Prize committee, calling smell “the most enigmatic of our senses,”

didn´t wave the checkered flag for smell until 2004-to Linda Buck, a professor at the University of Washington, and Richard Axel of Columbia University.

Here´s their explanation of smell: When I whiff Doberman breath, odor molecules travel up my nostrils and sweep over my olfactory epithelium, a postage-stamp-size patch packed with some 10 million neurons. On the tips of these neurons, receptor proteins serve as docking stations for the odorant molecules. Humans have at least 350 types of olfactory receptors, and each deals with just a few kinds of odorants, like locks that accept only a few keys. They can work alone or in combination. The energy of odorants binding to receptors is relayed to the brain´s olfactory cortex. The particular pattern of activated receptors tells you what you´ve smelled.

This gets to why television is in many ways simpler than Smell-O-Vision. Seeing in color involves processing information on a single parameter, the wavelength of light. The eye needs only three types of receptors-versus the nose´s estimated 350-to distinguish hues. Olfactory VR is difficult because there´s no R-G-B of smell, no three primary ingredients, or even a relatively manageable 50 or so, that you could load in the Scent Collar to produce any smell the way a desktop printer can produce any picture.

Because real-life odors can be staggeringly complex-it takes the precise interaction of more than 300 chemicals to produce the aroma of a strawberry-perfumers often work like sketch artists, trying to capture in a much simpler fashion the essence of the original.

Scent finalists in hand, I leave Arlien and head to a lab where fragrances are mixed. Perfumers in white coats sit at work bays, measuring liquids from the hundreds of bottles stacked around them. In the middle of the room, machines spin beakers of raw ingredients. Opposite from the work bays, perfumer Todd Nguyen sits at a computer. I uncap one of my bottles and put it under his nose. “Wet dirt,” he says after a short pause. He sniffs again.

“The main structure is verdol-the minty, wet smell. There´s patchone, which is drier; ethyl fenchol; and fenchone. Those notes together make your dirt note.” He takes another whiff. “To make the dirt more pungent, we probably added some birch tar-it smells like burnt wood, pretty common in anything barbeque. There´s some triplal to make it greener, and vertenex, an ozonic, earthly note, which also gives you the fresher part of wet dirt. A dash of eugenol, which smells like cloves, adds spice.

“A very nice interpretation,” he says, screwing the cap back on.

In the scent trade, Nguyen is a “nose,” somebody with an uncanny and well-practiced skill for analyzing and engineering smells. His efforts are aided by the high-tech tools-primarily gas chromatographs and mass spectrometers-that have transformed aroma manufacturing in recent years and allow researchers to determine a scent´s ingredients down to parts per billion.

In traditional perfumery, raw ingredients (rose petals, wood cuttings) are cooked, pressed, or macerated to produce the essential oils that are the building blocks of scent construction. The new tools in major scent labs, however, enable another approach. You can collect an air sample containing odorants, analyze it in the lab, and have your scientists attempt to synthetically construct those same odorant molecules. As my factory visit wraps up, I ask one of Nguyen´s lab mates if he would replicate, say, the smell of gun smoke in a dusty Tikrit alley. No, he says, because the profit incentive isn´t there yet. Could he? Almost certainly.

Jacki Morie was walking across an open field when she smelled it-an aroma so heart-wrenchingly wonderful that she stopped still, unable to move for five minutes. This was in Dallas in 1990, but she was lost, transported 40 years back. Morie can´t say what she smelled, or even provide a rudimentary description. All she knows is the scent was from when she was a baby, and the transfixing power of the experience convinced her that for VR to be truly successful, it must have smell.

Everybody has stories like this about aromas that trigger precise memories, often very sentimental ones. The concept resonates in literature, most famously in Marcel Proust´s Remembrance of Things Past, in which the smell of a tea-soaked madeleine provokes, well, past remembrances, thousands of pages´ worth (“But when from a long distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone . . . remain poised”).

The smell/memory/emotion connection is tantalizing to military simulation experts. A handful of studies have shown that odors can enhance your memorization skills. Some research supports the theory that odor-linked experiences form more distinct memories in your cluttered brain. (These reliable qualities are known as-what else?-Proustian characteristics.)

Findings like these encourage Morie. When I arrive at the ICT for my visit, her research assistant is putting the finishing touches on a paper about Scent Collar experiments done with soldiers at Fort Benning, Georgia. The primary finding: People tend to learn more in the state of emotional arousal that olfaction-enabled VR can provoke.

In her sunny corner office, Morie clears space on her desk and brings out dozens of scent bottles. I hand her the new ones, which she uncaps and begins smelling. The first forest fragrance is good, she says, with plenty of Douglas fir; the second one is even better; the third . . . no, too citrusy. Number two it is. I play my trump card, Wet Earth. “I like this one,” Morie says. “It has much more dirt in it than the one I used before for the culvert.”

Morie uses a glass pipette to draw half a length of Wet Earth and lets the liquid trickle out into an empty bottle. Then, for a fuller representation of the culvert, she adds a quarter of a pipette from a bottle labeled “Bat Guano” and an eighth of a pipette of “Mildew.” She passes me the mixture. “Not bad,” I say.

The first Scent Collar prototype was completed in 2002. The version Morie holds now was finished in 2005. If she can obtain additional funding (her Scent Collar reserves ran dry at the end of last year), she hopes to build a third version with 10 scent-emitting modules. Each of the Scent Collar´s four modules has a reservoir, which Morie now loads with a fragrance-soaked wick. Within each module, a small arm can move to open either two ports, one port or none, releasing a controllable amount of scent into a chamber above. Odorant molecules drift through the chamber, out a vent and up toward the user´s nose. For a stronger smell, a micro-fan in the chamber blows on a low or high setting. The release is triggered when the user reaches different points in the simulation. Producing only small, precisely targeted amounts of odor, the Scent Collar solves the top two problems plaguing room- and theater-scale systems: the difficulty of making rapid scent changes and of clearing the air of an old scent when you want to release a new one.

Morie checks the batteries. The collar is ready for its demonstration. First, though, we´re going on a field trip.

We´re in a hang glider. It dives into a river gorge, the air fragrant with pines, swoops through an orange grove, sweet with sun-warmed citrus, and glides over the ocean through currents of fresh, salty air. At last the glider touches down and we´re . . . back at Disney´s California Adventure, in a theater complete with levitating seats, a panoramic screen, gusting wind and piped-in smells.

Morie and I are on a smelling tour of the park. Shortcomings notwithstanding-the grove smelled like orange juice rather than blossoms and soil-theme parks have some of the best olfactory simulations around. Leaving California Adventure and entering Disneyland proper, we walk down “Main Street USA,” tantalized by the aromas of chocolate, caramel apple and waffle cone. The odors could be real or they could be fake, blasted by the hidden scent cannons that Disney calls Smellitzers. Boarding cars for a ride through the Haunted Mansion, we suddenly get a whiff of stale graveyard air.

Disneyland is an inspirational environment for Morie, and a familiar one. In the early 1990s, she worked at the University of Central Florida´s Institute for Simulation and Training, which works closely with the military and is near Disneyworld, where she visited often. When she changed jobs to teach computer animation at Disney Feature Animation, her offices moved to Disneyworld itself, and she and her colleagues were frequently called away from their desks to test new rides.

Morie´s theme park/Hollywood/military overlap isn´t as unusual as you might think. Central Florida and Southern California are the capitals of military and entertainment-world simulation, and the industries of fun and war swap technology, ideas and personnel. “You know the military-industrial complex, the thing Eisenhower warned us against?” Morie says as we head for the park exit. “Now we have the military-entertainment complex.”

Back at the ICT, I don the goggles and Scent Collar. My first, guileless mission ended with the attacking Doberman. For my second mission, I take a left out of the culvert and race down a dry riverbed to a car flipped on its side. I take cover behind it, then peek up at the sentry. After a couple minutes, he leans back to take a nap. I run up the hillside through the trees. I can smell them; I´m surrounded by them. I reach the corner of the building. Beside it a rebel is using a blowtorch to remove the serial number from a truck. A metallic smell fills my nostrils.

Maybe I´m not 100 percent in this virtual world. But I´m no longer completely in cubicle-land either. When Morie was setting up the demo, I tried it first without smell. It felt more or less like a fancy videogame. With smell, I feel much more like I´m in a real place. DarkCon is consuming me. Morie is saying something, but she sounds far away. I barely make out her words: “I think we´re losing him in there.”

James Vlahos wrote about the riskiness of everyday life in the July 2005 issue.

Hear more about author James Vlahos’s experience in the Army’s new smell simulator on the PopSci Podcast.