Rodeos are really a seven-part rebuke of death.

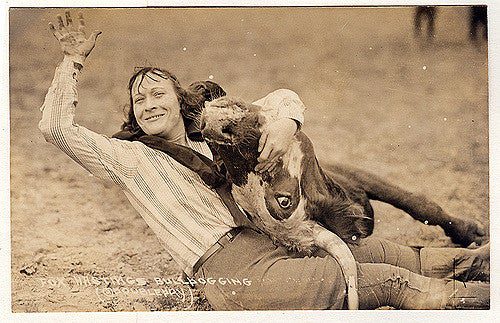

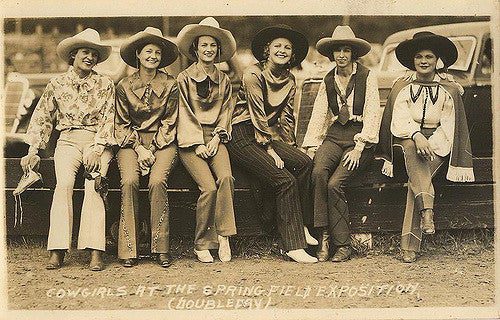

Steer wrestlers in studded chaps leap from their noble steeds to grab a cow by its horns until it topples over. (The legendary bulldogger Bill Pickett brought steer to heel by biting their lips.) Barrel racers, bedazzled boots gleaming, guide their horses in a tight clover at breakneck speeds. Tie-down and team ropers in embroidered pearl-snap western shirts lasso calves to the ground. Bull riders and their equine equivalents, saddle and bareback bronc riders, simply hang on for dear life.

There’s a long list of ingredients in the recipe for rodeo success: practice, style, an almost inhuman fearlessness (and, many critics say, an inhumane attitude toward animals). But perhaps the most important part is right under your cowboy boots. It’s the rodeo dirt.

“There’s clay, there’s sand, there’s loam,” says Matt Brockman, communications manager for the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo, which runs until Feb. 9 this year. “Depending on the particular needs, you may have more [of one than the others].” In Fort Worth—which at 123 years old is the nation’s longest-running rodeo—the floor is covered in a rich red clay. It’s dredged up from the bottom of the Brazos River, 50 miles to the west, and packed for the specific demands of the world’s rodeo stars.

“Some of those contestants are more concerned with dirt than others,” Brockman says. “To a barrel racer, dirt is extremely important.” Horses in this category need solid footing in order to make tight turns around the three barrels laid out on the competition floor. To keep the surface smooth—all the better for riding fast and sliding safely—Fort Worth has staff dedicated to raking the floor in between each barrel racing performance, to remove any divots and prepare the soil for the next performer.

“For the other events, it’s important to the extent that their horses can maintain their footing without slipping or falling,” Brockman says. “You don’t want it too wet, you don’t want it too dry.” Moisture content is also important to fans in the stands. “Our rodeo is held indoors. Having dust stirred up in the air doesn’t provide for a good spectator experience.”

Staffers water the dirt every day before competition with the goal of keeping the golden mean between mud and a dust bowl. It appears to be working: Fort Worth won third place in the 2018 Women’s Professional Rodeo Association Justin Best Footing Award for Texas.

Brockman and his peers rely on the expertise of soil scientists, like those at the Safe Arena Footing Committee, to prepare the perfect floor. The SAF standard is a three-layer rodeo cake. On top of a typical concrete stadium base, rodeos should place a base layer of dense soil, like clay or even gravel, at least 6 inches thick. Then, they should add a 4-inch cushion of firm, compacted dirt, and a final 3 inches of loose soil on top. The committee also advises on issues like water quality (salts, sodium, and bicarbonates can alter the composition of soils) and the ideal silt to clay ratio (one to four).

Rodeos may be major events, but they’re typically tenants, not landlords. Prior to the rodeo season, Fort Worth’s dirt is stored in a special outdoor bin at the Will Rogers Coliseum. It’s close to but carefully separated from other soils, like the cutting horse competition soil and the coliseum’s general purpose earth. Depending on the monthly mix, the 36-event rodeo might be sandwiched between a monster truck rally with its own dirt and a hockey game on ice.

The San Antonio Stock Show and Rodeo, which is held at the AT&T Center, has similar storage, according to Darci Owens, rodeo director. San Antonio’s 2,160 tons of soil dates back to a 1988 purchase from a dirt company outside Charlotte, Texas. It’s kept under a tarp for 11 months of the year, then hauled out for a few weeks of action. Workers sift out debris (mainly horse poop, or as the Houston Chronicle once called it, “gifts”) and systematically replenish it. “We determine if additional sand, clay or other materials are needed to maintain its composition,” Owens writes. Three days before the first performance, workers truck the soil in, load after load.

In San Antonio, the dirt “is laser-levelled and checked for an even depth,” Owens writes. But not every part of the floor in San Antonio is identical. Work crews, operating enormous earth movers, know that “adequate depth and soft padding helps reduce the pressure on joints and muscles as the athletes compete in their respective events,” she writes, and that different sports stress animals and humans in different ways. “In the riding events… the dirt is packed more firmly near the chutes so animals do not slip as they are bucking and have better traction,” she writes. “In the timed events, specifically, the barrel race, the dirt is looser around the barrels so it gives when the horses make the turn.” This year’s festivities begin Feb. 7.

The reasons for recycling dirt are mostly pragmatic. Storage costs are minimal, but replacing a whole arena’s worth of soil would cost $25,000 a year. But there’s something a little subtler at work. According to Kathryn Siefker, a curator at the Bullock Texas State History Museum, rodeo administrators, fans, and athletes all have a special affinity for their local mixture. What else explains the Houston rodeo’s decision bring their pile with them when they left the Astrodome?

When Siefker began working on the Bullock’s “Rodeo! The Exhibition” two years ago, she sought out competition footage and historical artifacts, like star roper Sam Garrett’s cables and a bronze statue of bulldogger Bill Pickett. But soil wasn’t really on her mind. “No, no, I had no idea going in that rodeo dirt was important,” she says. Once she got a tip from a consultant in the rodeo and started digging, she couldn’t deny the importance of a good footing.

The rodeo exhibit, which closes Sunday, ultimately featured two large beakers, amidst a sea of rhinestones, sweat, and tears. One was filled with Fort Worth’s dazzling clay, the other with Rodeo Austin’s brown loam. While every athlete has their own specific needs, Siefker says, in rodeo, “dirt has to be all things to all people.”