Like many researchers, Phil De Luna finds inspiration in nature — in this case, the way plants use photosynthesis to make food from carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight. He envisions a day when scientists will use water and renewable energy to transform carbon dioxide into products society can use, such as fuel, medicine, or feed for livestock. While scientists tend to talk about carbon capture and storage—one approach to fighting climate change — De Luna thinks the future instead will be about carbon capture and conversion.

“The world needs more solutions to climate change. If we can design and engineer technologies that use CO2 rather than fossil fuels to meet our chemical and fuel manufacture needs, then we can completely recycle carbon in a closed loop,” said De Luna, a doctoral candidate in materials science at the University of Toronto.

Humans are altering the climate by burning coal, oil and gas, releasing carbon that was once buried underground into the sky, increasing the volume of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Fuels made from captured carbon—instead of coal, oil, or gas — add no additional CO2 to the atmosphere when burned.

Once the technology that makes this happen becomes wide spread, “we can continue to meet the world’s energy demands using renewable energy, while also providing a source for the consumer goods and materials that we need every day,” De Luna added. “This technology has the potential to provide complete sustainability.”

Currently, carbon capture typically involves grabbing CO emissions from sources like coal-fired power plants, then storing them underground so they can’t enter the atmosphere and heat the planet. De Luna and his colleagues, including Oleksandr Bushnuyev, a University of Toronto postdoctoral fellow, are studying developing technologies that could make storage secondary — or even unnecessary. A study describing their work appears in the journal Joule.

“By using renewable energy to convert CO into a fuel, one can store that renewable energy, and then, when that fuel is burned, the CO can be captured again, closing the carbon cycle,” De Luna said. His team’s concept, which he described as being “at the cusp of becoming commercializable,” is a semi-finalist for the NRG COSIA Carbon XPrize, a $20 million competition to accelerate the development of technology that can capture CO and convert it to usable products.

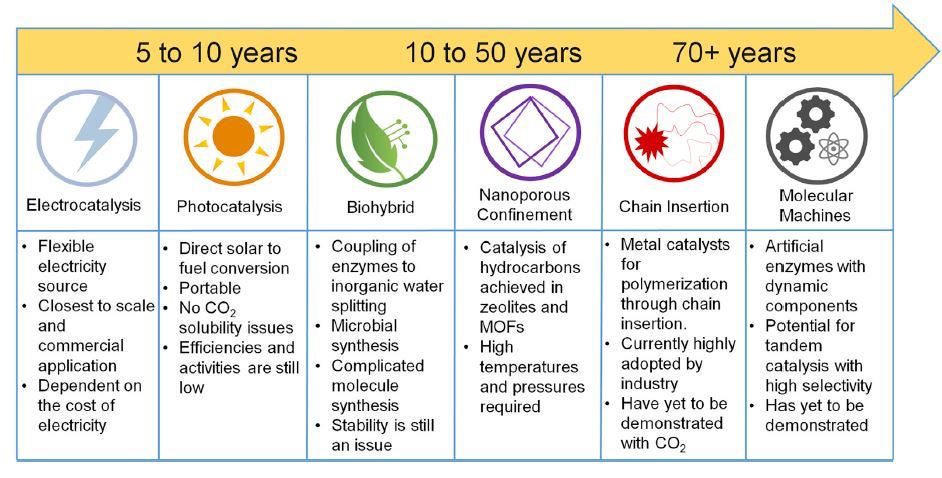

While conversion technology is still in its infancy, researchers believe the coming decades will bring major advances. Within five to 10 years, for example, electro-catalysis — which stimulates chemical reactions through electricity — could reduce the cost of turning carbon dioxide into fuel and other products. Within 50 or more years, nanotechnology could drive conversion, according to the scientists.

“This is still technology for the future,” Bushuyev said. “But it’s theoretically possible and feasible, and we’re excited about its scale-up and implementation. If we continue to work at this, it’s a matter of time before we have power plants where CO is emitted, captured, and converted.”

The researchers acknowledge that there are obstacles to be overcome, chief among them the cost of electricity needed to drive chemical reactions. But they believe the price tag will decrease as renewable energy becomes more widespread.

“At the heart of this technology is the catalyst, the material that converts CO, and work still needs to be done to make the catalyst more efficient, selective and stable over a long period of time before costs can come down,” De Luna said. “In terms of scale, it is an engineering matter at this point, and there are many people working on scaling up this kind of technology.”

He believes there is no danger that technology to recycle carbon dioxide would be a lifeline for coal- and gas-fired power plants to churn out carbon pollution. “Not at all,” he said. “The biggest issue with renewable energy penetration isn’t that people don’t want it. It’s that our needs as a society do not match when the sun shines or when the wind blows.

“The only way we can actually encourage clean renewable energy is to level out the energy supply so that intermittency issues are no longer a problem, and this technology provides a way to do that,” he said. “The majority of our hydrocarbon economy, which leads to things like plastic and building materials, are also derived from fossil fuels. If we can replace fossil fuels with captured CO, then we can solve the intermittency and energy storage problem, capture CO from the atmosphere and put it to work, and build plastics and materials out of an emission waste.”

The research was an attempt to gain “clear insight into whether this could be economically viable, and whether it’s worth the time to invest in it,” he said. Their work envisions “a pathway for what we can do with carbon dioxide conversion in the coming decades.”

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.