Bread basket

Sourdough bread, tangy and chewy, is my favorite bread for grilled cheese sandwiches (white cheddar only, please), pesto paninis, and eating an entire loaf in one sitting. To rise, this bread doesn’t rely on the packets of dried yeast you find in the baking aisle at the grocery story. Instead, it needs a starter—a living culture of wild yeast and bacteria. The first step to making good sourdough bread, then, is raising a proper sourdough starter from flour and water.

I’m well-versed in hand-braided challah, yeasty cinnamon rolls, and scratch-made English muffins, and sourdough seemed like a good next challenge. So I cleaned out a plastic Chinese takeout container—washing it a few times to clear out any lingering soy—and pulled out the kitchen scale. I tend to be a lazy baker, measuring ingredients by volume (cups and tablespoons). But serious bread making calls for more precision, which means measuring ingredients by weight.

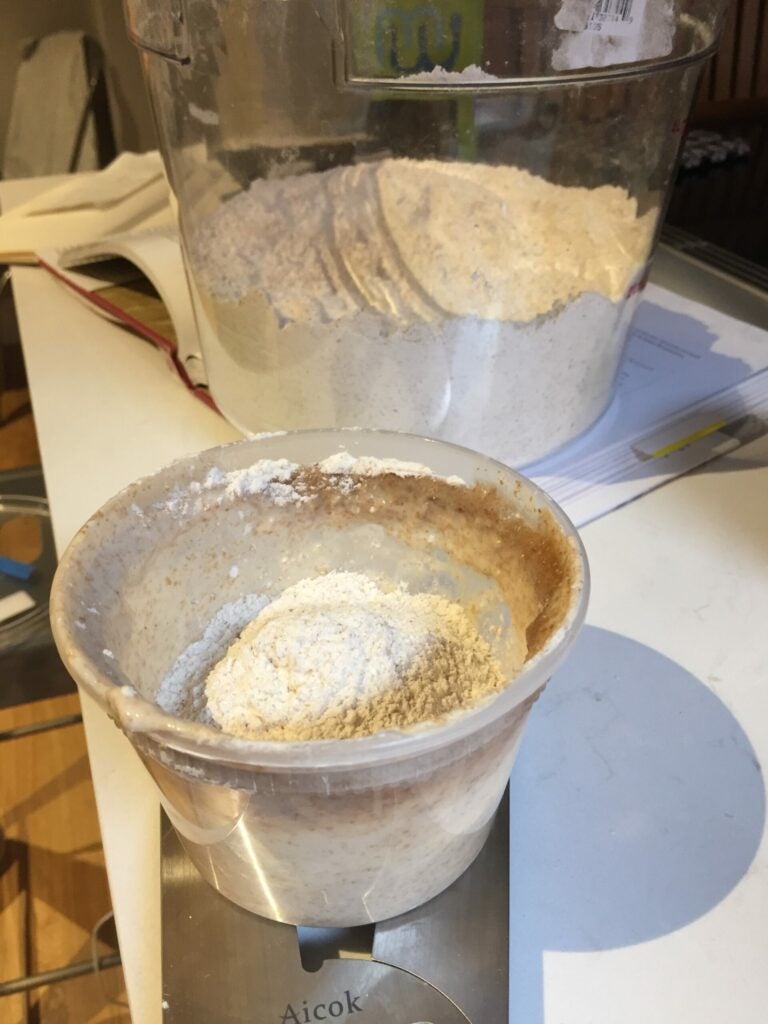

On the first day, I set my container on the scale and scooped in equal amounts of flour (I used a blend of half white, half whole wheat) and water. I added about four ounces of each ingredient and stirred them together into a thick batter. Then I covered the container with its lid (a clean towel will also work), set it on the counter, and walked away.

While I watched Netflix in the other room, a chemical reaction began in the simple mixture. Adding water to flour activates an enzyme called amylase, which breaks the flour’s chemically complex starches down into simple sugars. Those sugars make a perfect food for two types of microorganisms: wild yeast and a type of bacteria called Lactobacillus, the same tiny creatures that help chefs make fermented foods like kimchi, yogurt, and sauerkraut.

Within the container of sourdough starter, the wild yeast feeds on the newly-simplified sugars, pooping out carbon dioxide gas and ethanol, aka alcohol. Although the Lactobacillus consumes the same sugars, it produces different waste products: lactic and acetic acids, which raise the acidity of the mixture and will eventually contribute to the sour tang of the bread.

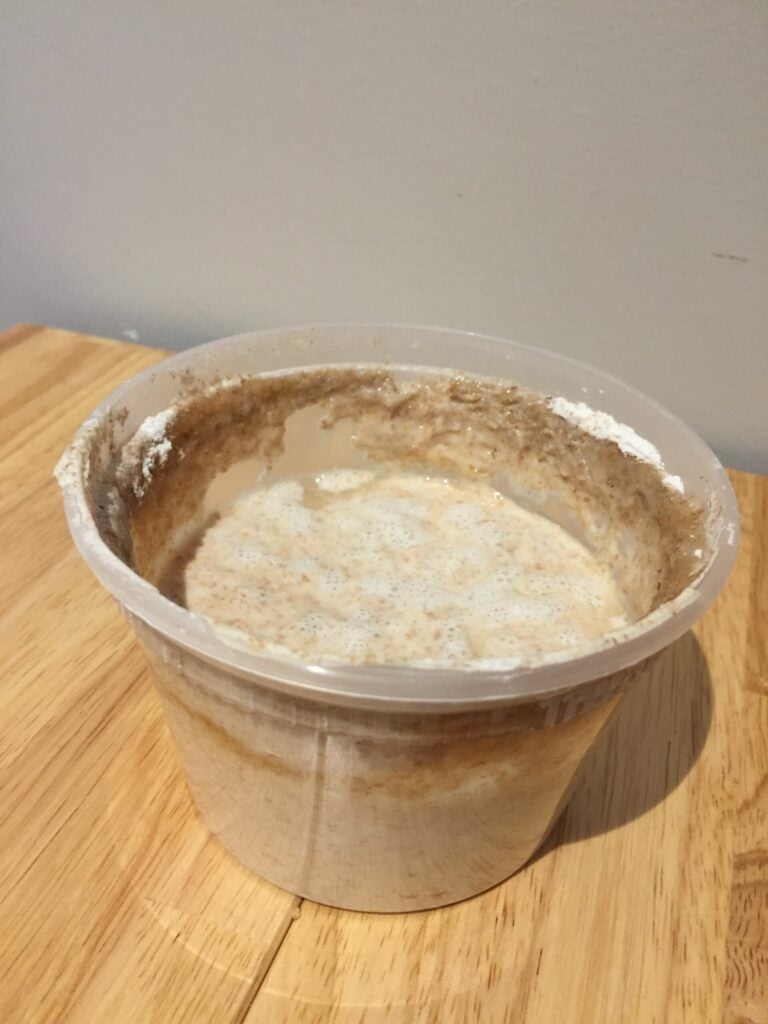

The next morning, I lifted the towel, and was thrilled to see tiny bubbles dotting the surface of the batter. These were a sure sign that I’d caught some yeast, and it was starting to churn out CO. Next, I had to keep the process going, which meant feeding the starter a fresh batch of flour and water. But if I just continued adding to the existing mixture, I’d quickly fill the container to overflowing. So I emptied about 70 to 80 percent of the starter into the trash. Then I added about three ounces of water and three ounces of flour to the remaining starter—fresh sugars for breakfast.

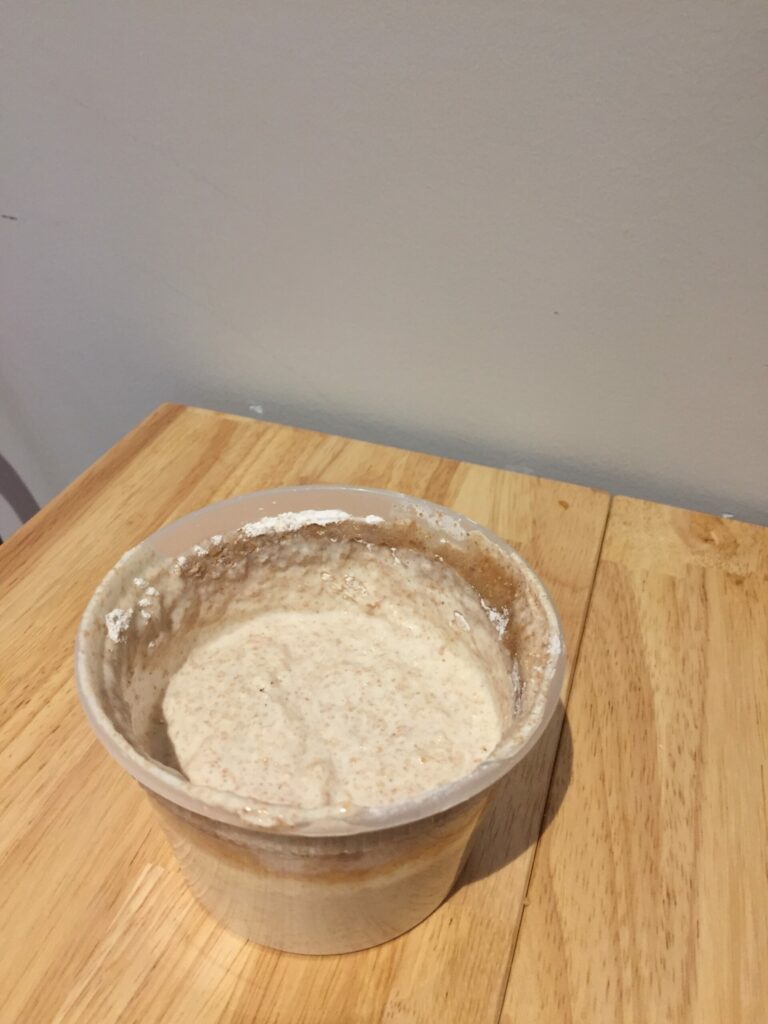

With regular feedings every day, the starter started to take on a distinctive (read: gross) smell, like vinegar and overripe fruit. Just as the bubbles showed that the yeast was active, the smell meant the bacteria were hard at work, manufacturing those tangy lactic and acetic acids.

To encourage both types of organisms to thrive, in addition to regular feedings, I made sure to keep the container at a stable room temperature. Anywhere between 50 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit should be fine, although different temperatures can affect the speed of the starter’s growth.

After about a week, the starter will stabilize, filling with bubbles and cycling through smells on a predictable timeline. If a small bit of starter is light enough to float in a cup of water, it’s ready for a marathon of bread-baking. I can taste the grilled cheese already.

Tools

- Kitchen scale

- Small, clean container

- Spoon

- Clean dish towel

Materials

- Flour

- Water