In a harbinger of future sea-level rise that could pose a serious threat to coastal communities, an iceberg the size of Delaware has broken free from an Antarctic ice shelf, leaving the rest of the shelf vulnerable to collapse.

The break in the Larsen C ice shelf — the most northern major ice shelf in the region—occurred Wednesday, according to Project MIDAS, a UK-based monitoring group.

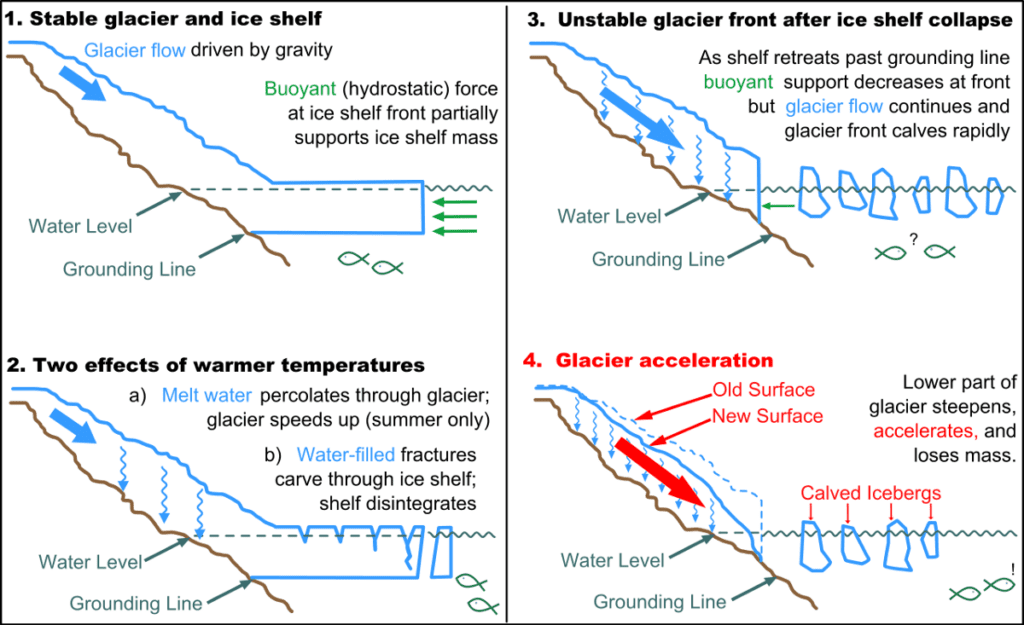

Ice shelves are the thick, floating ice at the edge of the continent, and they serve as buttresses, keeping onshore glaciers from sliding into the sea. Researchers have been monitoring the rift in the Larsen C shelf for years and became alarmed in December when the breach widened dramatically. At one point this spring, the rift grew by 11 miles in less than a week, leaving only eight miles left and raising fears that a complete break was imminent. More than six months later — in the middle of the Antarctic winter — the break has occurred.

“The situation with the Larsen ice shelf is a combination of fascinating and troubling, a tangible piece of a larger slow-motion disaster unfolding in front of our eyes,” said Michael Oppenheimer, professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton University. “We are seeing a microcosm of the future… a future that may already be inevitable and, if not, will likely be so if we transgress the 2º C warming target.”

Larsen C is about 1100 feet thick and rests at the edge of West Antarctica, blocking the glaciers that feed into it. All of the region’s ice shelves, including Larsens A, B, and C, impede the movement of Antarctic glaciers, which, if they float into the ocean, can hasten sea-level rise.

The Larsen A ice shelf collapsed in 1995 and the Larsen B shelf suddenly crumbled in 2002 after a similar rift developed.

“One of the processes causing the disintegration of the Larsen… is also implicated in the rapid changes in the Amundsen Sea area of West Antarctica — Thwaites glacier, Pine Island glacier,” said Oppenheimer, a long-time participant in the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. He explained that the loss of ice shelves will likely allow land-based ice into the ocean, causing additional sea-level rise.

“There is a relatively small amount of ice behind the Larsen, so even if it all disintegrated, the contribution to sea-level rise would be modest, a few inches,” he said. Still, even a few inches of sea-level rise is meaningful, especially when combined with storm surge in low-lying areas.

And what is happening with Larsen C is not an isolated problem. Cracks in other Antarctic ice shelves also have developed.

“There is several meters worth of ice behind the other ice shelves and more behind vulnerable ice shelves in East Antarctica. So what we are seeing is a vivid demonstration of what warm water and warm air can do to an ice shelf and the land-based ice sheet that the shelf has been restraining,” Oppenheimer said.

With the break, Larsen C lost more than 10 percent of its area, leaving the ice front at the most retreated position on record, according to Project Midas, a UK-based Antarctic research effort.

“This is just the latest empirical evidence for what scientists have increasingly concluded in recent years,” said Michael Mann, professor of meteorology at Pennsylvania State University and director of its Earth System Science Center. “Namely, that the West Antarctic ice sheet is less stable with respect to global warming than once thought, and its demise is occurring ahead of schedule, and with it, so is global sea-level rise.”

Kevin E. Trenberth, a senior climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said there have been conflicting theories surrounding the impact of climate change on the region.

“Warming of the atmosphere means that moisture can be carried farther inland, and one prospect that has been mentioned is that more snow could occur in Antarctica, which could contribute to lowering of sea level, countering trends elsewhere,” he said. “Observations of precipitation are poor, and we do not have good information on this aspect.”

Trenberth explained that waters around Antarctica are warming more than anywhere, undermining ice shelves. “This has gained support from various studies over time, so once again the outcome is more icebergs breaking away from Antarctica.”

“The key question is, ‘What does this mean overall?’” he said. “Is the West Antarctic ice sheet unstable and may become ungrounded, resulting in it melting and 20 feet of sea-level rise ultimately? The uncertainties are huge and the topic is important.”

Richard Alley, a glaciologist at Pennsylvania State University, agreed. Alley believes the shrinking of Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves is likely due to warming, though uncertainties abound.

“Think of all the ceramic coffee cups you have ever seen dropped on the floor,” he said. “Some have bounced, some chipped, some broken in two, some smashed. We all know that dropping a ceramic coffee cup on the floor risks breakage, but we would be hard-pressed to predict exactly what one cup will do. Exactly where this break will go on Larsen C, and how it will affect the probability of additional breaks behind it, fall into the category of predicting one break.

“We can surely improve our data, our understanding of the setting, and our models, and reduce the uncertainties for similar events in the future,” he said. “But there will always be some uncertainty. If one wishes to avoid really costly breakage… leading to meters of sea-level rise, the approach… is to leave a wide safety margin, which would mean limiting warming.”

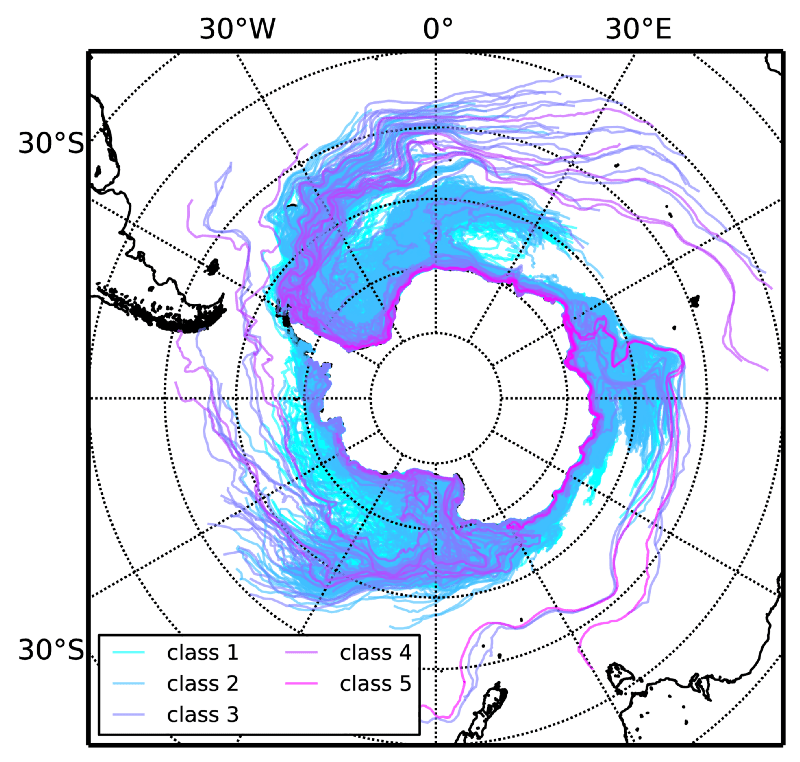

As for the fate of the breakaway iceberg, climate scientists have developed models that can predict its journey. Researchers at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research have figured out how Antarctic icebergs drift through the Southern Ocean.

When it comes to huge icebergs like the Larsen C, its motion is largely dictated by its weight and by the fact that the surface of the Southern Ocean is not flat but typically leans to the north. The sea level can be up to half a meter higher on the southern edge of the Weddell Sea or along the Antarctic Peninsula than at its center. How far it will drift depends on whether it remains intact or breaks up into smaller pieces, the researchers said. The iceberg also could run aground for a while.

“If it doesn’t break up, chances are good that it will first drift for about a year through the Weddell Sea, along the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula,” said Thomas Rackow, a climate modeler at the Wegener Institute and first author of the study. “Then it will most likely follow a northeasterly course, heading roughly for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.”

Because it is so heavy, Larsen C likely will survive for eight to ten years, according to the scientists’ computer models, a period regarded as the maximum life expectancy for even the largest of icebergs.

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.