When we get sick, there may be a time for starving and a time for stuffing. Depending on the type of infection plaguing us, fasting may be helpful — or it may be harmful, an experiment in mice indicates.

“Our study…sheds light on the biology behind the old adage ‘starve a fever, stuff a cold,'” wrote the researchers, who published the findings September 8 in the journal Cell.

When we fall ill from bacteria or viruses, we tend to become feverish and lethargic, and to shun food. How and whether these tendencies help us when we’re ill is difficult to determine.

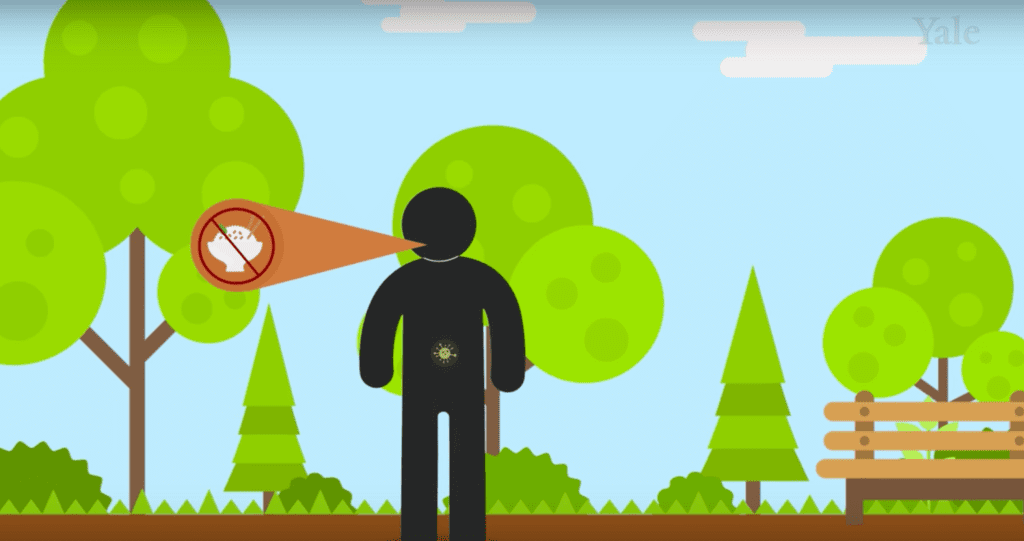

To investigate how loss of appetite might affect the immune system in sick animals, researchers infected some mice with the bacteria Listeria (a common cause of food poisoning), and some with the influenza virus.

“The question was whether fasting metabolism is protective or detrimental,” coauthor Ruslan Medzhitov, of Yale University, said in a statement.

When the mice were force fed, those with bacterial infections died—but those with viral infections were more likely to survive. The researchers determined that glucose in food was responsible for these divergent fates (rather than proteins or fats). When the team used drugs to block the mice from using glucose, the mice infected with bacteria survived, while their virus-ridden peers died.

Viral and bacterial infections induce different types of immune responses. So our metabolism might require different fuels to prevent inflammation from damaging the body. During a viral infection, glucose seems to be key. But during a bacterial infection, fasting benefited the mice by allowing them to use ketones, a different fuel that is produced when fat is broken down.

“Our work may have implications for how we feed infected patients in intensive care units,” coauthor Medzhitov said in a video released by Yale.

But it’s definitely too soon for these findings to translate into advice about how sick people should eat. This study focused on one strain of mice in a lab setting and only a couple of forms of infection. “It remains to be seen how these results apply to critical illness in humans,” Medzhitov and his coauthors wrote.