When he was little, Matthew Shifrin loved building with Legos, but his blindness prevented him from constructing sets from instructions.

“I drooled over large Lego sets on the internet, never thinking I’d be able to build them myself,” Shifrin writes in an article in the latest issue of Future Reflections, a magazine for parents and teachers of blind children.

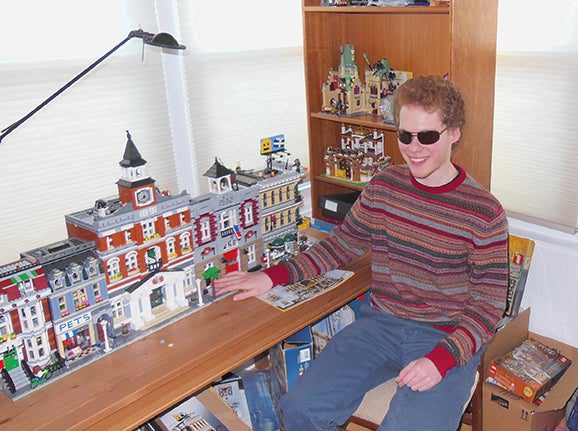

That changed on his thirteenth birthday when Shifrin’s friend, Lilya Finkel, gave him the gift of Lego access. She brought him a Lego set (Battle of Almut, 841 pieces) with the instructions written in a special notation that she’d invented, carefully describing each piece, its orientation, and its target location. Using a screen reader, Shifrin was able to follow the instructions and build a Lego set on his own for the first time. In the years since, Shifrin and Finkel have perfected the notation system, creating blind-accessible instructions for over twenty Lego sets including Hogwarts Castle, Volkswagen T1 Camper Van, and Luke’s Landspeeder.

“Lego is an excellent brain strain,” Shifrin writes. “It’s a great way to improve spatial awareness and spatial reasoning–areas where blind people sometimes have trouble.”

Blind children would benefit from more opportunities to build with Legos, writes Mark Riccobono, president of the National Federation of the Blind, in the same issue of Future Reflections. It can help them learn to build mental maps, he writes, a crucial skill for navigating independently. He calls for a “Lego revolution for the blind” centered around the creation of a library of text-based Lego instructions written in a common language. Shifrin and Finkel’s work appears to be a big step towards that goal.