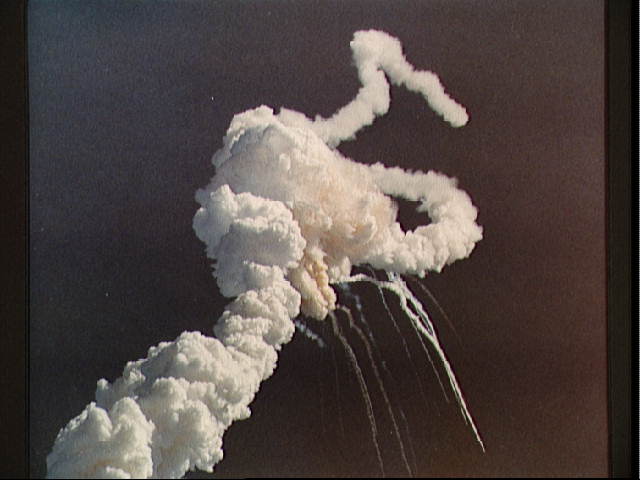

Thirty years ago, on the morning of January 28, 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger launched with a crew of seven people aboard, including the first civilian American teacher ever selected for a NASA spaceflight mission. They were supposed to spend a full week in orbit, but 73 seconds after launch, one of the solid rocket boosters propelling the shuttle into orbit failed, causing the shuttle to explode, killing all aboard. But the legacy of the shuttle, and that of the crewmembers, lives on today.

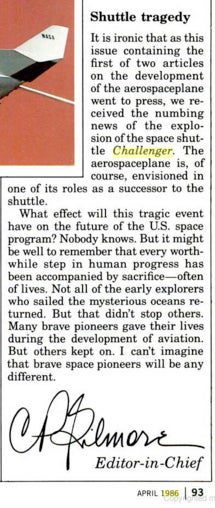

At the time of the disaster, Popular Science was of course very interested in the U.S. space program and the launch. However, as a monthly print magazine unable to respond in real-time to breaking news events, the first mention of the disaster came in the April 1986 issue. And it was mentioned only briefly in the “What’s News” section at the end of the magazine, in an update from then editor-in-chief C.P. Gilmore. acknowledging that the print publication cycle prevented the magazine from including more comprehensive coverage. As he wrote:

PopSci’s first mention of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

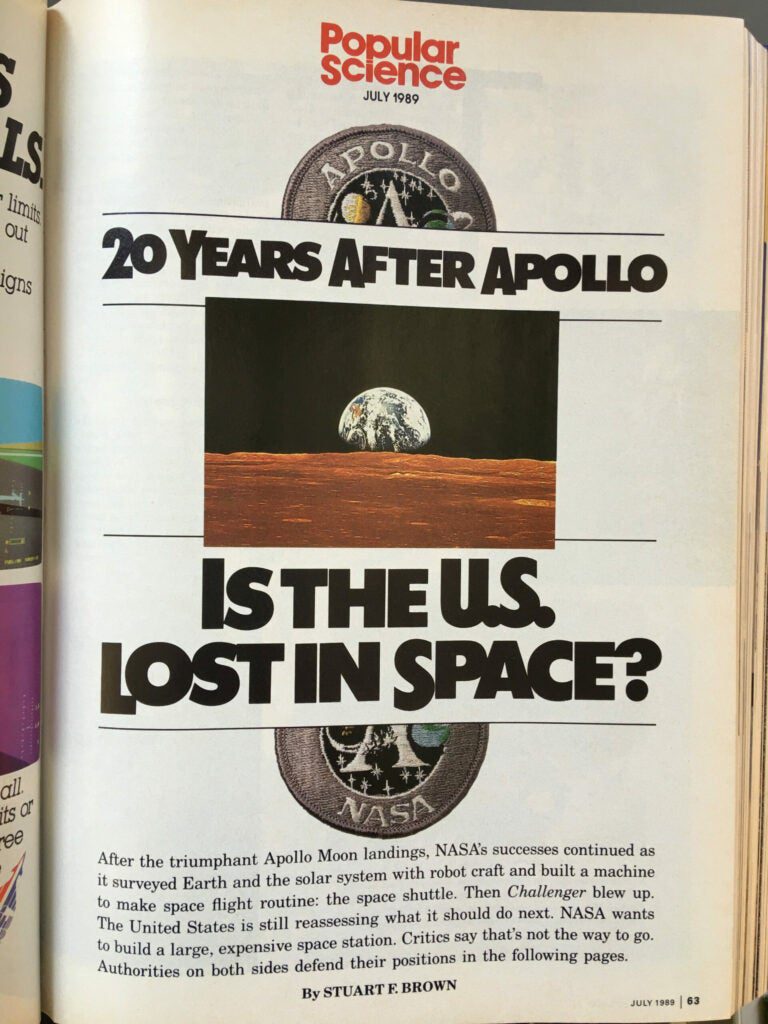

Popular Science went on to cover more about the disaster itself, and the implications for the future of human space exploration, several years later — in a July 1989 article entitled, “20 Years After Apollo: Is The U.S. Lost In Space?”

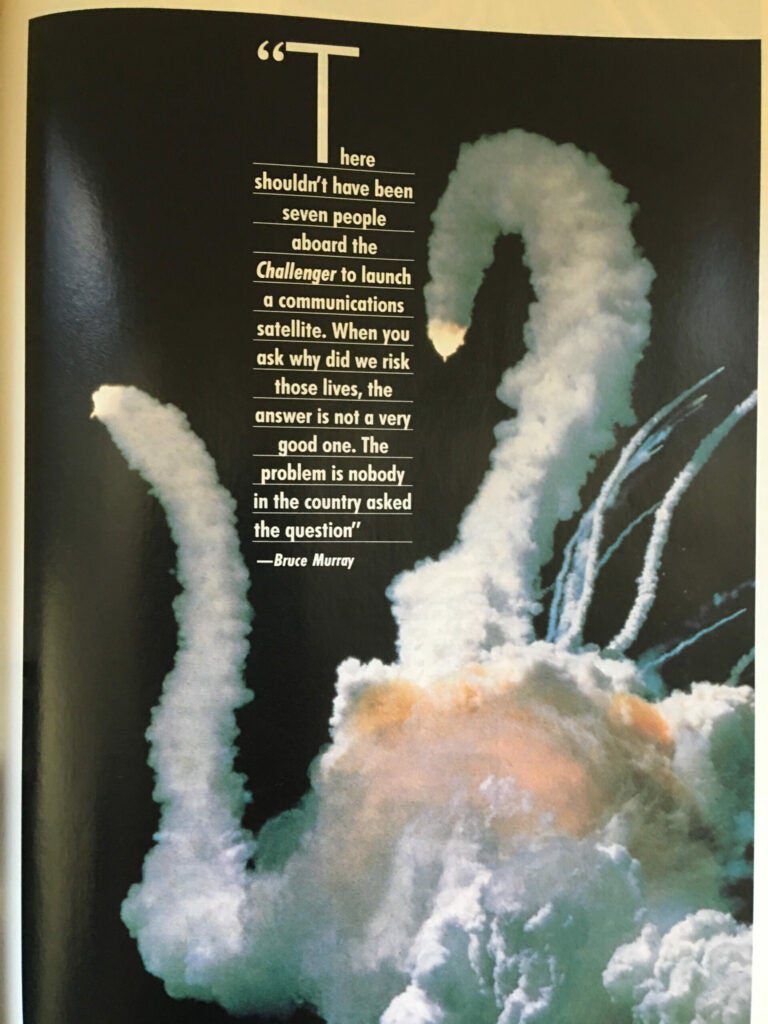

Popular Science’s coverage of the Challenger disaster in 1989

Challenger referenced in the 1989 pages of PopSci

In this longer article, writer Stuart F. Brown calls into question the idea that NASA should build a space station (what would later become the International Space Station), and interviews four spaceflight experts in a kind of roundtable discussion about what NASA should be doing as the 20th century ends and the 21st century begins.

Brown centers the discussion and the article itself around astronaut Sally Ride’s 1987 report to the NASA Administrator, a famous document in nerdy spaceflight circles, which calls for NASA to devote most of its resources to one of four main goals: 1.) better studying Earth from space, including via a space station 2.) exploring the outer solar system 3.) building a moon outpost 4.) sending humans to Mars and establishing a colony there in the early 21st century.

NASA, of course, ended up pursuing mostly goals one and two. And the Space Shuttle program went on for many more years, ferrying astronauts into orbit and to the space station itself, before finally being retired in 2011.

And yet, another Space Shuttle-like craft may soon launch again: NASA just recently awarded a cargo contract to Sierra Nevada, a private company that makes a reusable spaceship called the Dream Chaser, which is expected to begin ferrying supplies to the International Space Station in 2019.

You can read these stories, and full old print issues spanning most of the 144 years of Popular Science, via our digital archives (a partnership with Google Books).